Science in School

States of matter & phase transitions teach article.

This article was originally published as a CERN teaching module .

Explore phase transitions between different states of matter through a series of engaging hands-on experiments.

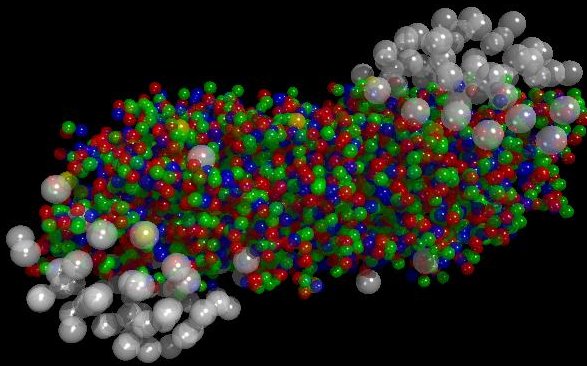

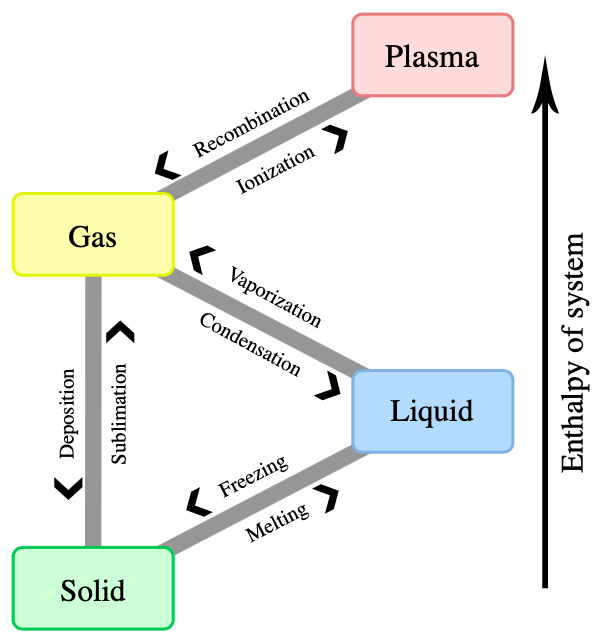

Matter occurs in different states: solid, liquid, gaseous and plasma. When external conditions (such as temperature or pressure) change, the state of matter might change as well. For example, a liquid such as water starts becoming a gas when it is heated to its boiling point or starts to freeze when it is cooled to its freezing point. A state of matter with very high energy is plasma. Here, some of the orbital electrons are not bound to atoms or molecules anymore. Hence, plasma is a gas of free electrons and ions.

Phase transitions often occur in nature, but they are also used in many technologies. In particular, several particle detectors rely on phase transitions. Furthermore, high-energy physics research can create an even more energetic state of matter, the so-called quark-gluon-plasma.

Therefore, high-energy physics provides a fruitful and exciting context to discuss states of matter and phase transitions with your students. Moreover, there are several fun experiments that allow students to study phenomena on their own. Below, we highlight some of our favourite experiments and explain how to link them to CERN physics and technologies. When using these experiments with students, make sure to let them predict the outcome of the experiment first, before conducting the experiment and observing the result.

Vaporization – liquid to gas

When you heat water up to its boiling point, bubbles of water vapour start to form as water changes from a liquid to a gaseous state. Similarly, when opening a bottle of sparkling water, bubbles start to form. Here, the decrease in pressure caused by opening the lid starts the vaporization process.

An interesting effect can be observed at surfaces that provide tiny impurities, for example, cellulose fibres inside a glass. These impurities provide starting points for bubbles to form, so-called nucleation sites. When pouring sparkling water into a glass, small amounts of gas get trapped inside or around small dust particles such as cellulose fibres.

A very similar principle forms the basis of the bubble chamber particle detection technique. Bubble chambers are filled with a superheated liquid that basically really wants to turn into a gas. Therefore, any small disturbance or impurity will start the bubble formation process inside a bubble chamber. Indeed, when ionizing particles fly through this superheated liquid, they will ionize the molecules on their way. These ions will then act as nucleating sites and bubbles will form around them. In this way, the track of an ionizing particle leaving a trail of ions can be visualized when taking photographs of the bubble trails at the right moment. (Find out more about bubble chambers here .)

Today, bubble chambers are no longer used for research at CERN. However, they have recently found a new role in dark matter research, for example, in the PICO project in Canada .

Hands-on experimentation with vaporisation: dancing raisins in sparkling water

One of our favourite experiments is the ‘dancing raisins experiment’ that allows students to study the role of nucleation sites in sparkling water.

- Sparkling water (or any other sparkling and transparent drink)

- A few raisins

- Fill a glass with a sparkling liquid.

- Add a few raisins.

- Observe the raisins, in particular, their movement.

Modifications

- You can also study other types of potential ‘dancers’ or other types of sparling liquids for example, different types of noodles, frozen blueberries, lentils, corn etc. Try to find the best combination.

- Add the raisins directly to a bottle of sparkling water and compare their movement with the lid on and off.

Explanation

The raisins will soon start moving up and down in the sparkling water. What happens? The surface of the raisins is not as flat at the surface of the glass. Instead, the surface of raisins includes many tiny fibres that act as nucleation sites. Hence, tiny bubbles of carbon dioxide gas form at the surface of the raisins. When enough gas bubbles are attached to the surface of a raisin, it will start to rise to the surface (buoyancy, Archimedes’ Principle). Once the raisins reach the top, the bubbles pop because they are exposed to the air. Without their ‘floating devices’ the raisins will sink again.

Melting – solid to liquid

When the internal energy of a substance increases, e.g. by applying heat or pressure, a solid will eventually become a liquid. For example, ice cubes or a wax candle start melting when applying heat, whereby the pressure remains constant. However, solids such as ice or wax differ in their melting points. Whereas ice melts at a temperature of about 0°C, wax melts at about 40°C. When a substance reaches its melting point, the temperature of the substance does not increase further even if constant heat is applied, as long as there is some solid left to melt. Thus, the applied heat for melting a solid is also referred to as latent heat. Only when all the solid has turned into a liquid state does the temperature begin to rise again.

Hands-on experimentation with melting: cooling bath

Among all the experiments in which students can study the melting process, making a cooling bath may be the coolest. All joking aside, it’s indeed really cool! In addition, cooling is essential for running the LHC. Check out CERN’s cryogenics webpage for more information.

The minimum temperature of a regular ice-water mixture is the melting point of ice at 0°C. You could use such a mixture as a cooling bath, e.g., for cooling a bottle of lemonade. However, there is one trick to make your cooling bath even cooler, i.e. to cool your lemonade more efficiently. The melting point of a substance such as ice can be depressed by adding a salt such as sodium chloride. Hence, an ice-water-salt mixture ends up at a lower temperature than an ice-water mixture.

- Water, cold

- Crushed ice (alternatively: ice cubes, plastic bag, and hammer), the ratio salt : ice must be 1 : 3

- Thermometer (alternatively: multimeter with a temperature sensor, up to -20°C)

- Beaker glass, 600 ml

- Beaker glass, 400 ml

Safety Note

- Use a cold-resistant glass.

- Supervise younger students when working with cooling baths.

- Put the 400 ml beaker glass in the 600 ml beaker glass to create an insulating container.

- Add crushed ice to the internal beaker glass.

- Add enough cold water to cover the ice.

- Measure the temperature of the water-ice-mixture (should be about 0°C).

- Add salt (remember, the ratio salt : ice must be 1 : 3).

- Stir the mix until the ice melts.

- Measure the temperature of the water-ice-salt-mixture (should be up to -20°C).

Hands-on experimentation with melting: buoyancy of ice

Another really cool experiment is to study how melting icebergs affect sea level or how melting ice cubes affect the level of your sugary summer drink.

Since salt (or sugar) water is denser than water, the buoyant force exerted on ice is bigger. Thus, ice cubes don’t sink as much in salt (or sugar) water as they would in water. Therefore, the level of the salt (or sugar) water rises, when the ice cubes melt, whereas it remains the same for water. This effect occurs, for example, when the ice cubes in your sugary summer drink melt. Unfortunately, it also reinforces the negative effects of climate change: Icebergs are large chunks of ice that break off from glaciers (e.g. in Greenland). They are made of water, not salt water. Thus, sea level rises not only when icebergs drift into the sea, but also when they melt. However, the additional effect of the melting ice is comparatively small. [1]

- water, cold

- Salt (or sugar)

- 6 ice cubes

- 2 Beaker glasses, 50ml

- Fill the 2 beaker glasses half full with water.

- Add 3-4 tea spoons of salt (or sugar) in one beaker glass and stir.

- Put 3 ice cubes in each beaker glass.

- Add water to the salt (or sugar) water until the liquid level is the same in both beaker glasses and stir.

- Mark the liquid level on both beaker glasses.

- Wait until the ice cubes have melted.

Additional information

One can also observe that the ice cubes melt slower in salt (or sugar) water than in water. This is another consequence of the higher density of salt (or sugar) water in comparison to water.

Did you know that CERN is engaged with the Sustainable Development Goals ? Find out more about how CERN contributes to a better planet on the CERN knowledge transfer website .

Condensation – gas to liquid

The cloud chamber was one of the first particle detectors. Here, the most important aspect is a supercooled supersaturated alcohol vapour, which is essentially a very cold and very wet gas, that really wants to become a liquid. Indeed, any disturbance of this vapour might start the condensation process. When high-energy ionising particles fly through this vapour layer, they leave a trail of ions behind. These ions then trigger the condensation process acting as condensation nuclei. Therefore, the trail of ions turns into a trail of small drops that can be observed with your eyes or a camera under the right lighting conditions. This relatively easy principle allowed particle physicists to record particle tracks already 100 years ago.

Today, the CLOUD experiment at CERN investigates cloud formation to find out more about climate change. Interested? Watch a TEDEd lesson by Kirby, Richer, & Comes (2016): Cloudy climate change: How clouds affect Earth’s temperature.

Hands-on experimentation with condensation: cloud in a bottle

There are several experiments in which your students can study condensation. The cloud in a bottle experiment shows in an impressive way, how a rapid decrease in pressure can trigger the phase transition condensation. There are several videos and instructions on how to make a cloud a bottle online. Depending on the effort and equipment, the effect will be impressive to observe even as a demonstration or easy to do in a safe way as a hands-on experiment. Thus, we highlight our favourite two methods below. If you have access to dry ice, you can also let your students build their own cloud chamber using dry ice and isopropanol alcohol .

1. Impressive demonstration

- 30 ml of disinfectant (about 70% alcohol, or purer alcohol)

- A bottle of spray duster

- A 1 l transparent PET bottle

- Water and flour

Safety note

- Wear safety goggles to protect your eyes against splashes of alcohol and unforeseen expansions of your PET bottle.

- You should also wear gloves to protect your skin from alcohol, especially, if you use very pure alcohol.

- Make a small hole into the lid of the bottle to squeeze in the tube of the spray duster.

- Use a flour-water mixture to seal the opening (alternatives: blue tack, playdoh, glue …).

- Add 30 ml of disinfectant (or relatively pure alcohol) into the PET bottle and turn the bottle to make sure the inner surface is covered with alcohol.

- Put on the lip carefully, all connections need to be airtight.

- Add about 20 pumps of spray duster into the sealed bottle.

- Carefully open the lids (attention, pressure build-up!).

- Now you should see a very dense cloud consisting of drops of alcohol in your bottle.

- You can also use a ball or bike pump to increase the pressure inside the bottle – however, you might need to add some additional condensation nuclei in this case.

- Additional condensation nuclei: open the lid, squeeze the bottle gently and blow out a match in front of the lid, release the pressure of the bottle to soak in some of the smoke particles (the smoke will provide additional condensation nuclei).

- It also works with water instead of alcohol, but it’s not that impressive.

2. Easy hands-on experiment

- 10 ml of disinfectant (about 70% alcohol, or purer alcohol)

- A 0.5 l transparent PET bottle

- Wear safety goggles to protect your eyes against splashes of alcohol.

- Wear safety gloves to protect your skin from alcohol, especially, if you use very pure alcohol.

- Make sure to monitor students during this activity.

- If the students are young, only the tutor or teachers uses the matches to make sure no student accidentally sets the alcohol inside the bottle on fire.

- Add the disinfectant (or pure alcohol) into the PET bottle.

- Close the bottle with the lid.

- Turn the bottle to make sure the inner surface is covered with alcohol.

- Now, open the lid, squeeze the bottle gently and blow out a match in front of the lid.

- Release the pressure of the bottle to soak in some of the smoke particles (the smoke will provide additional condensation nuclei).

- Close the lid.

- Squeeze the bottle as much as you can and release the pressure of your hands suddenly.

- Now, you should see a cloud appearing inside the bottle.

The melting of ice floating on the sea introduces a volume of water about 2.6% greater than that of the originally displaced sea water: Noerdlinger PD, Brower KR (2007) The melting of floating ice raises the ocean level . Geophysical Journal International , 170: 145-150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-246X.2007.03472.x

- Watch a video of the raisins experiment on Twitter or Facebook .

- You can download the video of the raisins experiment from CERN CDS Videos .

- States of matter and supercooling: an overview .

- More experiments on phase transitions and states of matter .

Institutions

Download this article as a PDF

Share this article

Subscribe to our newsletter.

- High School

- You don't have any recent items yet.

- You don't have any courses yet.

- You don't have any books yet.

- You don't have any Studylists yet.

- Information

Phase Change Lab - A science lab experiment with pre-post evaluations and results. Can be used

Biology (bio101), asbury university, recommended for you, students also viewed.

- Accuracy & Precision Lab

- Sand & Salt Lab - A science lab experiment with pre-post evaluations and results. Can be used

- Delsha Howard Chapter 8 Terms

- G BIO101 Week 3 QUiz Study Guide-1

- Species interaction data collection

- Week 4 terms

Related documents

- Week 3 terms

- Bioterms week 2 - bio terms

- Exam 3 Study Guide

- Exam 1- Study Guide

- Quiz 1- Carbohydrates

- Course workCourse workCourse workCourse work

Preview text

Physical Science Name: T. Partner: None Phase Change Lab Hr: 4 Date: 1.

Materials ● Thermometer ● Hot plate ● Large beaker (500ml) ● Ice

Background: 1. Find a phase change diagram for water.

a. The diagram is shown above. 2. List the physical properties of water. Why is water unique? a. Cohesion/Surface Tension, Conduction of Heat, Latent Heat of Vaporization + Fusion, Heat Capacity, Density, and Viscosity b. It’s composition, unusual properties, and importance to human life. 3. Why is water called the “universal solvent”? a. Because it’s capable of dissolving a variety of different substances

- Fill the beaker with ⅓ of ice.

- Add water until the ice is covered.

- Add 5g of sugar.

- Record the temperature of the liquid in the table.

- Heat the beaker.

- Record the temperature of the liquid every 30 seconds.

7. Record observations of the water/mixture every 30 seconds.

8. turn off the hot plate after 2 minutes., 9. graph results on a piece of graph paper..

Time (s) Temp (C) Observations 0 4 In its original ice-water form. 30 5 60 8 90 8 120 8 150 6 Ice is beginning to melt. 180 8 210 9 240 10 270 12 300 13 Ice is continuing to melt. 330 14 360 14 390 15 About half of the ice is melted. 420 16 ¾ melted 450 17 ⅘ melted 480 18 510 20 Most of the ice is melted. 540 24 570 25

3190 100 Boiling Point 3220 100 3250 100 3280 100 Lots of Bubbles 3310 101 Data Complete

Analysis 1. What happened to the temperature of the water as the ice melted? As the water boils? a. As the ice was melting - at certain points - the water would temp would decrease slightly because the ice would make it cooler. b. When the water boiled, the temperature increased. 2. Where do you think that the energy from the burner was going? a. It traveled around the beaker glass, through the water, and created steam. 3. Did the dissolved substances change the physical properties of the water? Explain. a. The dissolved substances gave the water a slightly different color and appearance. The salt made it take longer for the ice to melt. The sugar and salt made it take less time for the water to start boiling. 4. What is the melting point of the solution? a. (In Celsius) || Salt: 23, Sugar: 23, and Water: 32. 5. What is the boiling point of the solution? a. (In Celsius) || Salt: 102, Sugar: 100, Water: 100 6. Identify the segment(s) on your graphs where a solid is present? a. Salt: 0-6 minutes, Sugar: 0-10 minutes, Water: 0-10 minutes 7. Identify the segment(s) on your graphs a liquid is present only? a. Salt: 10-15 minutes, Sugar: 10-14 minutes, Water: 11-15 minutes 8. Identify the segment(s) on your graphs where gas is present? a. Salt: 15-21 minutes, Sugar: 14-32 minutes, Water: 15-41 minutes 9. Identify segments on your graphs which indicate phase changes are taking place.

a. Salt: solid (0-6 minutes) liquid (10-15 minutes) gas (15-21 minutes b. Sugar: solid (0-10 minutes) liquid (10-14 minutes) gas (14-32 minutes) c. Water: solid (0-10 minutes) liquid (11-15 minutes) gas (15-41 minutes)

- Multiple Choice

Course : Biology (Bio101)

University : asbury university.

- Discover more from: Biology Bio101 Asbury University 206 Documents Go to course

- More from: Biology Bio101 Asbury University 206 Documents Go to course

- More from: AM AM Alex Mister 999+ impact 999+ Otis College of Art and Design Discover more

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

7: Liquids and Solids and Phase Changes

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 481008

- Marco Zimmer-De Iuliis and Anna Galang

- University of Toronto Scarborough

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

The great distances between atoms and molecules in a gaseous phase, and the corresponding absence of any significant interactions between them, allows for simple descriptions of many physical properties that are the same for all gases, regardless of their chemical identities. As described in the final module of the chapter on gases, this situation changes at high pressures and low temperatures—conditions that permit the atoms and molecules to interact to a much greater extent. In the liquid and solid states, these interactions are of considerable strength and play an important role in determining a number of physical properties that do depend on the chemical identity of the substance. In this chapter, the nature of these interactions and their effects on various physical properties of liquid and solid phases will be examined.

- 7.1: Introduction In the liquid and solid states, these interactions are of considerable strength and play an important role in determining a number of physical properties that do depend on the chemical identity of the substance. In this chapter, the nature of these interactions and their effects on various physical properties of liquid and solid phases will be examined.

- 7.2: Intermolecular Forces The physical properties of condensed matter (liquids and solids) can be explained in terms of the kinetic molecular theory. In a liquid, intermolecular attractive forces hold the molecules in contact, although they still have sufficient kinetic energy to move past each other. Intermolecular attractive forces, collectively referred to as van der Waals forces, are responsible for the behavior of liquids and solids and are electrostatic in nature.

- 7.3: Properties of Liquids The intermolecular forces between molecules in the liquid state vary depending upon their chemical identities and result in corresponding variations in various physical properties. Cohesive forces between like molecules are responsible for a liquid’s viscosity (resistance to flow) and surface tension. Adhesive forces between the molecules of a liquid and different molecules composing a surface in contact with the liquid are responsible for surface wetting and capillary rise.

- 7.4: Phase Transitions Phase transitions are processes that convert matter from one physical state into another. There are six phase transitions between the three phases of matter. Melting, vaporization, and sublimation are all endothermic processes, requiring an input of heat to overcome intermolecular attractions. The reciprocal transitions of freezing, condensation, and deposition are all exothermic processes, involving heat as intermolecular attractive forces are established or strengthened.

- 7.5: Phase Diagrams The temperature and pressure conditions at which a substance exists in solid, liquid, and gaseous states are summarized in a phase diagram for that substance. Phase diagrams are combined plots of three pressure-temperature equilibrium curves: solid-liquid, liquid-gas, and solid-gas. These curves represent the relationships between phase-transition temperatures and pressures. The intersection of all three curves represents the substance’s triple point at which all three phases coexist.

- 7.6: The Solid State of Matter Some substances form crystalline solids consisting of particles in a very organized structure; others form amorphous (noncrystalline) solids with an internal structure that is not ordered. The main types of crystalline solids are ionic solids, metallic solids, covalent network solids, and molecular solids. The properties of the different kinds of crystalline solids are due to the types of particles of which they consist, the arrangements of the particles, and the strengths of the attractions bet

- 7.7: Key Terms

- 7.8: Key Equations

- 7.9: Summary

- 7.10: Exercises These are homework exercises to accompany the Textmap created for "Chemistry" by OpenStax.

Get Your ALL ACCESS Shop Pass here →

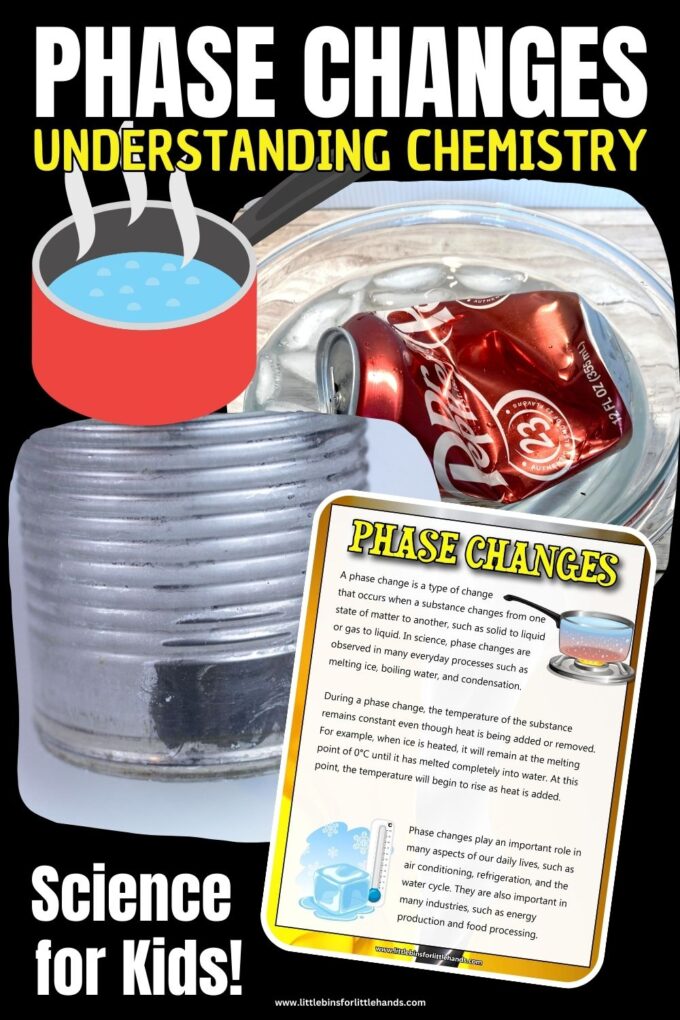

What Is Phase Change

What is a phase change? Learn about changing states of matter with a simple definition of phase change and everyday examples. Explore phase changes in science with easy, hands-on experiments kids will love and more. Fun science projects for kids of all ages!

What Is A Phase Change?

A phase change is a physical process that occurs when a substance changes from one state of matter to another, such as solid to liquid or gas to liquid. Energy is needed to change phases of matter.

A phase change is not a chemical change , because the chemical composition of the substance remains the same even though its appearance has changed. Instead phase changes are a type of physical change .

Find more examples of physical change and chemical change !

Why Does A Phase Change Occur?

Phase changes occur because there is a change in the energy of a system. Some phase changes require the addition of energy by heat, and some require the removal of energy by heat.

For example; changing a liquid, where the molecules are close together, to a gas, where the molecules are farther apart, requires energy in the form of heat. This enables the molecules to break apart from each other.

The stronger the forces, the more energy is needed to overcome them. A solid will require more energy than a gas because it has stronger intermolecular bonds.

Learn more about the characteristics of solids, liquids and gasses.

Phase changes from solid to liquid, liquid to gas or solid to gas, require energy and are endothermic .

Phase changes from gas to liquid, liquid to solid and gas to solid, release energy and are exothermic .

Types Of Phases

There are 6 types of phase changes. The 4 common phase changes you would be familiar with, are melting, freezing, boiling, and condensation.

- The phase change from solid to liquid is called melting .

- The phase change from liquid to gas is called boiling .

- The phase change from gas to liquid is called condensation .

- The phase change from liquid to solid is called freezing .

Sublimation and Deposition Phase Change

Two other types of phase changes are called sublimation and deposition . In these phase changes, the substance transfers from solid to gas or gas to solid without passing through the liquid phase.

- Solid to gas is called sublimation .

- Gas to solid is called deposition or de-sublimation.

Sublimation can happen with snow. If the air is very dry, the snow turns into water vapor without becoming a liquid in the process. Sublimation is an exothermic process.

An example of deposition is when water vapor in the atmosphere changes directly into ice, such as when frost is formed. Deposition is an endothermic process.

Phase Changes of Water

Phases changes of water include:

- solid to liquid – melting ice

- liquid to gas – boiling or evaporating water

- gas to liquid – condensation of water vapor

- liquid to solid – freezing water

Does one phase take more energy than another? The change to gas takes up the most energy because in order to do so the bonds between the particles have to completely separate.

The bonds in a solid only have to loosen up a bit to change phase such as a solid ice cube changing to liquid water.

During a phase change, the temperature of the substance remains constant even though heat is being added or removed.

For example, when ice is heated, it will remain at the melting point of 0°C until it has melted completely into water. At this point, the temperature of the water will begin to rise as heat is added.

10 Examples Of Phase Changes

Phase changes play an important role in many aspects of our daily lives, and in industry. Here are a few ideas, can you think of any more?

- making ice cream

- making chocolate

- making LEGO crayons

- dehydrating food

- burning liquid fuel in a camping stove

- air conditioning

- coolant in refrigeration

- hot and cold water storage systems

- melting gold

- water cycle

FREE Phase Change Info pack to get started!

Share examples of phase changes and the fun science behind them with this free printable phase changes guide.

Phase Change Experiments

Here are some fun examples of phase change experiments that use everyday household items. What could be easier!

Want to introduce the concept of phase change to younger kiddos? Check out our ice play activities for tons of fun ideas for ice melting sensory play!

Crushing Soda Can

Who would have thought the condensation of water (gas to liquid) could crush a soda can!

Freezing Bubbles

This is a fun phase change experiment to try in the winter. Can you turn liquid bubble mixture into a solid?

Freezing Water Experiment

Explore the freezing point of water and discover what happens when you freeze salt water. All you need are some bowls of water and salt.

Frost On A Can

A fun winter experiment for anytime of the year. Turn water vapor into ice when it touches the surface of your cold metal can.

Ice Cream In A Bag

Make a yummy frozen treat using ice and salt. Turn liquid milk and cream into a solid you can eat!

Ice Melting Experiment

What makes ice melt faster? Try three fun and easy to set up ice science experiments.

What happens to ivory soap when you heat it? It’s all because water changes from a liquid to a gas.

Making Soap

The process of making soap from a simple glycerin base involves several phase changes. Even better you end up with a fun surprise at the end!

Melting Chocolate

A super simple science activity that you get to eat!

Melting Crayons

Recycle your old crayons into new crayons with our easy instructions. Plus, melting crayons is also a great example of a reversible phase change from solid to liquid to solid.

Solid Liquid Gases

Observe the phase changes in water from solid to liquid to gas in a fun and easy way. Perfect for young kids, as well as older kids too!

This is a fun activity to do in the winter, when you have snow! Turn liquid maple syrup into an edible snow candy. Don’t have snow, you can use the freezer!

Water Evaporation

Investigate how different factors such as temperature and airflow affect the rate of water evaporation.

Compare how fast different everyday items melt in the sun, including ice cubes. A fun phase change experiment to do in the summer!

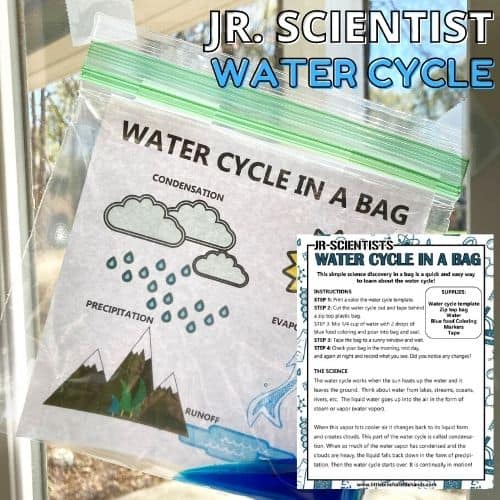

Water Cycle In A Bag

Not only is the water cycle important for all life on earth, it is also a great example of phase changes of water, including evaporation and condensation.

Science Experiments By Age Group

We’ve put together a few separate resources for different age groups, but remember that many experiments will cross over and can be re-tried at several different age levels. Younger kiddos can enjoy the simplicity and hands-on fun. At the same time, you can talk back and forth about what is happening.

As kiddos get older, they can bring more complexity to the experiments, including using the scientific method , developing hypotheses, exploring variables , creating different tests, and writing conclusions from analyzing data.

- Science for Toddlers

- Science for Preschoolers

- Science for Kindergarten

- Science for Early Elementary Grades

- Science for 3rd Grade

- Science for Middle School

Helpful Science Resources To Get You Started

Here are a few resources that will help you introduce science more effectively to your kiddos or students and feel confident yourself when presenting materials. You’ll find helpful free printables throughout.

- Best Science Practices (as it relates to the scientific method)

- Science Vocabulary

- All About Scientists

- Free Science Worksheets

- DIY Science Kits

- Science Tools for Kids

- Scientific Method for Kids

- Citizen Science Guide

- Join us in the Club

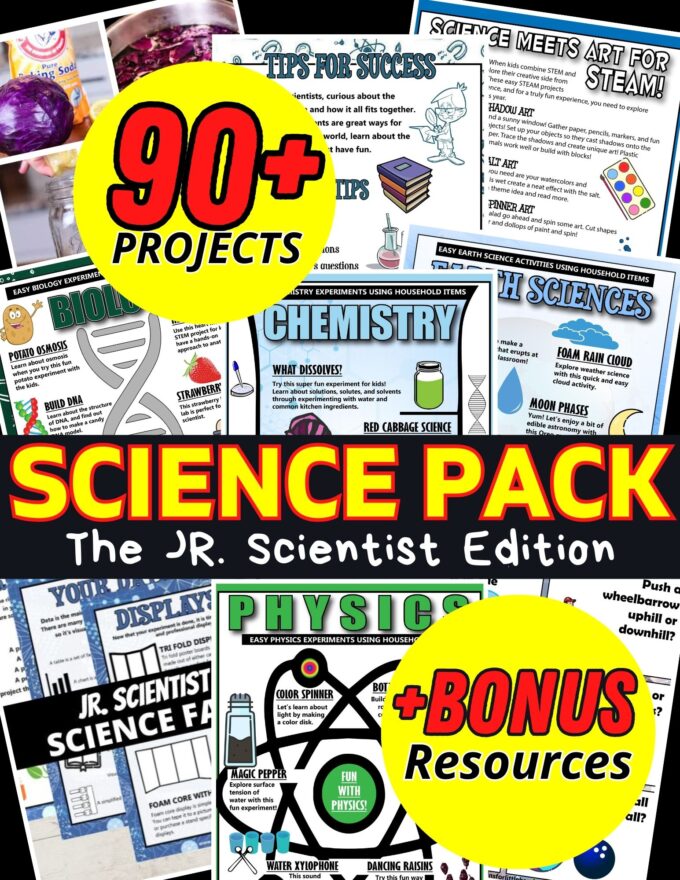

Printable Science Projects For Kids

If you’re looking to grab all of our printable science projects in one convenient place plus exclusive worksheets and bonuses like a STEAM Project pack, our Science Project Pack is what you need! Over 300+ Pages!

- 90+ classic science activities with journal pages, supply lists, set up and process, and science information. NEW! Activity-specific observation pages!

- Best science practices posters and our original science method process folders for extra alternatives!

- Be a Collector activities pack introduces kids to the world of making collections through the eyes of a scientist. What will they collect first?

- Know the Words Science vocabulary pack includes flashcards, crosswords, and word searches that illuminate keywords in the experiments!

- My science journal writing prompts explore what it means to be a scientist!!

- Bonus STEAM Project Pack: Art meets science with doable projects!

- Bonus Quick Grab Packs for Biology, Earth Science, Chemistry, and Physics

Subscribe to receive a free 5-Day STEM Challenge Guide

~ projects to try now ~.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Fusion, vaporization, and sublimation are endothermic processes, whereas freezing, condensation, and deposition are exothermic processes. Changes of state are examples of phase changes, or phase transitions. All phase changes are accompanied by changes in …

Fusion, vaporization, and sublimation are endothermic processes, whereas freezing, condensation, and deposition are exothermic processes. Changes of state are examples of phase changes, or phase transitions. All phase changes are accompanied by changes in the energy of a system.

Jan 15, 2021 · Explore phase transitions between different states of matter through a series of engaging hands-on experiments. ©CERN. Matter occurs in different states: solid, liquid, gaseous and plasma. When external conditions (such as temperature or pressure) change, the state of matter might change as well.

Phase changes are fundamental processes in thermodynamics. Understanding how temperature behaves during these changes is crucial for various scientific and practical applications. This experiment seeks to answer the scientific question: What happens to the temperature of a substance during a phase change? Hypothesis:

These experiments demonstrate that the phase of matter depends on temperature. The process of melting and freezing, and evaporation and condensing, should be discussed in terms of the change in structure of the materials as well as change in volume.

phase changes of water in this experiment. How can you connect this to natural phenomena, like rain? Based on what you have observed, how do you think rain clouds form? Draw a picture of the process in your science notebook. What are some similarities and differences between this process in the natural world and the process in our experiment?

Background: 1. Find a phase change diagram for water. a. The diagram is shown above. 2. List the physical properties of water. Why is water unique? a. Cohesion/Surface Tension, Conduction of Heat, Latent Heat of Vaporization + Fusion, Heat Capacity, Density, and Viscosity b. It’s composition, unusual properties, and importance to human life. 3.

Jun 29, 2024 · 7.4: Phase Transitions Phase transitions are processes that convert matter from one physical state into another. There are six phase transitions between the three phases of matter. Melting, vaporization, and sublimation are all endothermic processes, requiring an input of heat to overcome intermolecular attractions.

Nov 10, 2024 · A phase change is a physical process that occurs when a substance changes from one state of matter to another, such as solid to liquid or gas to liquid. Energy is needed to change phases of matter.

In this experiment, students are introduced to the effects of changes in crystal structure (“phase”) in metals, specifically in high carbon steels and in the shape memory alloy “Nitinol.”

Water Phase Change Lab Water can be found on the Earth in three phases: solid, liquid, and gas. Water will change phases when energy is added or taken away from the individual water molecules. During these changes the water molecules change their appearance, which means that phase changes are PHYSICAL changes. Your goal