The Jam Study Strikes Back: When Less Choice Does Mean More Sales

The Jam Study is one of the most famous experiments in consumer psychology, and new research to be published in the Journal of Consumer Psychology supports the Jam Study’s controversial conclusion; offering consumers less choice can be good for sales . Critically, the study reveals when precisely offering less choice may enhance your sales.

If you’re not familiar with the original Jam Study, it’s here . Basically, the study, which was conducted at upscale Bay-area supermarket Draeger’s Market by psychologists Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper, found that consumers were 10 times more likely to purchase jam on display when the number of jams available was reduced from 24 to 6. Less choice, more sales. More choice, fewer sales. Weird, huh?

This phenomenon, replicated in a variety of product categories from chocolate to financial services to speed dating, has come to be known as ‘Choice Overload’ or the ‘ Paradox of Choice ‘. It’s a paradox because rationally speaking the more choice you offer your customers, the more sales you should make simply because you’ll be satisfying more needs better. But research has showed that choice actually can be demotivating and get in the way of sales. Why?

Psychologically, the Paradox of Choice is not so much of a paradox because the more options you give people, the more time and effort they have to invest in making a choice – something they may not be prepared to do. Moreover, giving people a smorgasbord of options puts a psychological burden on them because what you are actually doing is giving them more opportunity to make the wrong choice, regret it and blame themselves.

Nevertheless, the Jam Study and follow-up studies has remained controversial; surely giving your customers more choice must be a good thing, right? Indeed, a meta-analysis of studies in 2010 found that the inverse link between choice and purchase likelihood is far from consistent.

But now a new study, ‘ Choice overload: A conceptual review and meta-analysis ‘ by Kellogg researchers at Northwestern University Alexander Chernev and Ulf Böckenholt (and Joseph Goodman) has re-analaysed the data from 99 Paradox of Choice studies and isolated when reducing choices for your customers is most likely to boost sales

- When people want to make a quick and easy choice (effort-minimizing goal)

- When making the right choice matters/you are selling complex products (the decision task is difficult)

- When you show options that are difficult to compare (greater choice set complexity)

- When your customers are unclear about their preferences (higher preference uncertainty)

So the Jam Study strikes back; more choice can harm sales – but probably only when one or more of these four criteria are met.

Dr Paul Marsden

Chartered psychologist specialising in consumer behaviour, wellbeing and technology. University lecturer at UAL and consultant consumer psychologist with Brand Genetics.

Join the discussion Cancel reply

11 comments.

Thank you! I’ve seen this study and the project. It was interesting to read the analysis of your work.

Hi Stacy, I really enjoy reading your blog and these have been some of my favorites this year as well. I am fairly new to DIY projects in general … We recently bought a house and are slowly repainting interior. I have done a couple furniture makeovers and I’m currently working on two dressers for my kids rooms. I noticed that you highly recommend the Home Rite paint sprayer. I’m wondering if it might be worth it for me to invest in that for furniture, the six panel interior doors that we have on each of our rooms and closets. I’ve also thought of refinishing the wood cabinets in the bathrooms and kitchen. Will the sprayer that you use and have recommended be good for these purposes? Do you feel that it is easy to use and easy to clean? Do you clean it in between each used or can you save it for the next coat paint?

Hi! Love this.

Just FYI, links to The Jam Study don’t work.

It’s a paradox because rationally speaking the more choice you offer your customers, the more sales you should make simply because you’ll be satisfying more needs better. I’m wondering if it might be worth it for me to invest in that for furniture, the six-panel interior doors that we have on each of our rooms and closets.

Hello I really enjoy reading your blog and these have been some of my favorites this year as well. I am fairly new to DIY projects in general … We recently bought a house and are slowly repainting interior. I have done a couple furniture makeovers and I’m currently working on two dressers for my kids rooms.

Tim Hartford covers the topic in his new book, The Data Detective. The many reproductions have demonstrated that, on average, the described effect does not exist. It is of course disappointing that studies disproving a popular theory have such difficulty getting published and are never given the same attention.

I love to eat fruit so this is a great product for me!

Inception’s complex storyline and stunning visuals make it a must-watch.

I am thankful for the cutting-edge knowledge and insights you have shared.

The way you presented complex information so simply is remarkable.

Further reading

UX Happiness Insights: Engagement Sucks

UX Happiness Insights: Time-Saving Experiences Boost Happiness by 8%

Two Need-to-Knows from Trendwatching’s Future of CX Report

Nudge Psychology – All 93 Behavior Change Techniques Listed and Summarised + Free App

EgoTech makes Millennials 16% more narcissistic as they age?

Enchanted Objects (and the future of digital branding) – Speed Summary

Digitalwellbeing.org.

Digital wellbeing covers the latest scientific research on the impact of digital technology on human wellbeing. Curated by psychologist Dr. Paul Marsden ( @marsattacks ). Sponsored by WPP agency SYZYGY .

- Art & Culture

- Financial Literacy

- Innovations

- Media Literacy

- Opportunities

- Sustainability

- Sustainable Fashion

The Paradox of Choice: Jam Experiment

The freedom of choice. Different people infer different things from this conundrum, but what all of them have in common is the option of choosing. As a matter of fact, the saying “the more freedom you have, the more choices you have” is so deeply embedded in society that it would not occur to anyone to question it. Well, luckily, it did, as a result of which the paradox of choice was discovered, changing the game in key spheres of human endeavour.

On a daily basis, people face various products, brands, models, and alternatives so everyone can choose something that fits. But have you ever wondered how many choices are actually enough? How many types of yogurts, smartphones, cars, services, material things, lifestyles, etc. should there be for one actually to make a good choice and eventually be satisfied? The more the better? It turns out that quite the opposite is the case.

This theory was created as a result of the Jam study , one of the most famous experiments in consumer psychology ever undertaken, conducted at the upscale Bay-area supermarket Draeger’s Market by psychologists Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper . According to the design of the experiment, on one day, the store’s customers were offered 24 different types of jam in the supermarket. On the following day, however, the number of jam types was reduced to just 6. Having analysed the relation between the number of jam types offered and the sales of jam on a given day, the researchers discovered a significant difference between the two cases. Namely, Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper found that consumers were 10 times more likely to purchase jam on display when the number of types available was reduced from 24 to 6. In other words, that meant that the less choice there was, the more sales there were, and vice versa.

These results challenged what people thought they knew about human nature and the determinants of well-being. From the perspective of both psychology and business, people had assumed that the relationship between choice and well-being must be straightforward. That is to say, the more choices people have, the better off they are. Namely, in psychology, the benefits of choice have been associated with a person’s autonomy and control. On the other hand, in business, the advantages of choice have been related to the benefits of free markets in general.

The reason for the opposite behaviour was explained as choice overload . This idea rests on the understanding that the more options you give people, the more time and effort they have to invest in making a choice. Therefore, we observe a diminishing marginal utility in having alternatives. That is to say, each new option reduces the feeling of satisfaction and well-being. Moreover, being exposed to numerous options puts a psychological burden on people, because what you are actually doing is giving them more opportunities to make the wrong choice and regret their choice afterward. Therefore, ironically, instead of the promised freedom, what we get with so many options is confusion and demotivation about making a decision. In other words, the freedom of choice, providing there are too many of them, makes it hard to choose at all.

Lowered Satisfaction

If we, however, overcome the feeling of confusion and the resulting, so-called paralysis and make a choice, we inevitably end up less satisfied with the decision made, because the feeling that we could have made a better choice, for instance by picking one of the alternatives, lowers the level of satisfaction significantly, usually making us experience regret, even if the decision was good after all. All of this would not obtain if fewer choices were being offered.

The way in which we value things depends greatly on what we compare them to. This has a direct relation to the basic reality of opportunity cost . Naturally, given numerous alternatives, it is easier to imagine all the possible advantages and benefits we would gain by the means of obtaining one of the alternatives. Opportunity cost, therefore, subtracts from satisfaction about the eventual choice, even if we choose well.

The Escalation of Expectation

Another aspect influenced by the abundance of choices is our expectations. With all the alternatives we have the expectation of how good things should be going up. Consumers start to believe that out there in the vast sea of available choices, there should be a perfect one. So even when we get something fairly good, we still think that there must be something better. It is good if you actually have found the perfect item, but normally, we end up feeling that something is still missing, even we have made a good decision.

Just consider one of the last times you went shopping, where you had a perfect image of what you wanted and what it should look like, yet you ended up unsatisfied, discouraged, or even angry because you simply did not like anything. Now imagine that instead of a huge shopping mall, with several shops offering hundreds of outfits, you had fewer offerings. Wouldn’t this make it easier for you to choose? Maybe not, but this would definitely lower your expectations, making you like the things which are just good enough, setting aside the image of total perfection.

Self-Criticism and Blame

With any type of decision, there is a certain level of responsibility. In the case of the limited number of offers and the wrong choice made, the responsibility goes to ‘the world’ or, more precisely, to market and supply. However, if there are so many options being supplied and we are the ones who decide what to choose, the responsibility becomes our burden. This is where self-criticism comes from, resulting in a totally negative experience. According to the studies by David Myer , depression has evolved significantly in the industrial age and even more in recent years. One of the contributors to this fact is the aforementioned freedom of choice because when we make a wrong choice, we blame ourselves and think that we are the ones who are at fault. This is both incredible and paradoxical because most of the choices are actually good. But the amount of possible alternatives overwhelms us and has a massive negative influence.

As a surprising result, an abundance of options does not help but, on the contrary, hurts. It makes it hard for us to make a choice and be satisfied even with the most sophisticated and personalised offers. The solution to this, however, is not monopolisation or returning to the system where shortages were commonplace. As a matter of fact, there are places in the world, where there is still a huge lack of alternatives. In those places, people do not struggle with making choices, simply because they have none. Therefore, if it were possible to give up some of the alternatives we have to those people and societies who have too few, not only would their lives would be improved but also ours. This is something which in economics is called the Pareto improving move .

Redistribution of income can make everyone better off, including rich and poor people, and manage the existing imbalance between societies, eventually giving the desired satisfaction and sense of well-being.

Photos: Shutterstock / Photomontage: Martina Advaney

Support us!

All your donations will be used to pay the magazine’s journalists and to support the ongoing costs of maintaining the site.

Share this post

Interested in co-operating with us.

We are open to co-operation from writers and businesses alike. You can reach us on our email at [email protected] / [email protected] and we will get back to you as quick as we can .

Where to next?

Balancing Academics and Extracurricular Activities: A Guide

Hey there, superstar! Balancing academics and extracurricular activities can be a juggling act, but with the right approach, you can excel in both. Whether you’re into sports, music, art, or…

Breaking Down Barriers: Promoting Inclusivity and Diversity

Introduction Inclusivity and diversity are vital for a thriving society and workplace. Inclusivity ensures all individuals feel valued, while diversity celebrates varied backgrounds and experiences. Promoting these principles fosters innovation,…

Developing Resilience: How to Bounce Back from Adversity

Introduction Resilience is our ability to recover from difficulties and adapt to life’s challenges. It’s what helps us bounce back stronger when life knocks us down. In both personal and…

Building Strong Social Networks: Tips for Young People

Building a strong social network is crucial for personal and professional growth. For young people, these connections provide support, opportunities, and a sense of belonging. Here, we explore the importance…

The Power of Networking: Building Connections for the Future

Introduction Networking is a powerful tool for personal and professional growth. Building strong connections can open doors to opportunities, provide support, and facilitate knowledge sharing. This article explores the importance…

The Paradox of Choice

Behavioural Science

Unraveling the mysteries of consumer behavior: a deep dive into the classic jam experiment.

- Introduction: Decoding Consumer Choices

As a seasoned marketer, I’ve learned that understanding consumer behavior is akin to unlocking a treasure trove of insights that can propel your business to new heights. One seminal study that sheds light on this intricate web of decision-making is the classic jam experiment conducted by Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper.

- Setting the Stage: The Jam Dilemma

Picture this: you stroll into a grocery store, greeted by rows of colorful jars filled with delectable jams. The choices seem endless, yet daunting. Should you opt for the tried-and-tested strawberry jam or venture into uncharted territory with exotic flavors like mango-peach? This dilemma encapsulates the essence of consumer decision-making – a delicate balance between familiarity and exploration.

The Experiment Unveiled

Intrigued by the nuances of choice, Sheena Iyengar, a pioneering psychologist, devised an experiment to explore how consumers navigate the abundance of options. The premise was simple yet profound: What happens when you present shoppers with a plethora of choices versus a more limited selection?

- Methodology: From Shelves to Survey

Iyengar and Lepper set up a tasting booth in a gourmet grocery store, showcasing an extensive array of jams – a whopping 24 varieties. On alternate days, they pared down the selection to a mere six flavors. Customers were invited to sample the jams and, if inclined, make a purchase.

The Surprising Results: Quality vs. Quantity

The findings of the jam experiment were nothing short of revelatory. While the extensive display attracted more attention, with throngs of curious shoppers milling around, it was the smaller selection that emerged victorious in terms of sales.

- Quality Overwhelms Quantity

Despite the allure of abundant choices, consumers faced with a limited selection were more likely to make a purchase. Delving deeper, Iyengar and Lepper discovered that too many options led to decision paralysis – a phenomenon where the abundance of choices hinders rather than facilitates decision-making.

Implications for Small Business Owners

Small business owners, listen up. While the classic jam experiment may seem like a simple study conducted in a grocery store, its implications are profound, especially for those of you navigating the complex world of marketing on a tight budget. Let’s delve into how these findings can revolutionize your approach to product offerings, customer experience, and overall business strategy.

- 1. Product Assortment and Decision Overload

One of the key takeaways from the jam experiment is the concept of decision overload. As a small business owner, you may feel compelled to offer a wide range of products or services to cater to diverse customer preferences. However, the study suggests that too many options can overwhelm consumers, leading to decision paralysis and, ultimately, fewer purchases.

Action Point: Instead of inundating your customers with an extensive array of choices, focus on curating a select assortment of products or services that align with your brand identity and cater to your target audience’s specific needs. By offering fewer options, you can streamline the decision-making process and increase the likelihood of conversion.

- 2. Positioning and Differentiation

Another crucial insight from the jam experiment is the role of positioning and differentiation in consumer decision-making. Participants were more likely to make a purchase when presented with a limited selection of jams, highlighting the importance of standing out in a crowded marketplace.

Action Point: As a small business owner, it’s essential to identify your unique selling proposition (USP) and communicate it effectively to your target market. Whether it’s superior quality, innovative features, or exceptional customer service, emphasize what sets your brand apart from competitors. By carving out a distinct niche, you can attract customers who value what you have to offer and are willing to make a purchase.

- 3. Customer Engagement and Experience

Beyond product assortment and positioning, the jam experiment underscores the significance of customer engagement and experience. The researchers found that participants were more satisfied with their choices and more likely to return for future purchases when they had a positive interaction with the product.

Action Point: Invest in creating memorable experiences for your customers at every touchpoint, from the moment they discover your brand to post-purchase interactions. Whether it’s through personalized marketing campaigns, responsive customer support, or seamless online shopping experiences, prioritize building meaningful connections with your audience. By fostering loyalty and satisfaction, you can turn one-time buyers into repeat customers and brand advocates.

- 4. Data-Driven Decision Making

Lastly, the jam experiment highlights the value of data-driven decision-making in marketing. By analyzing consumer behavior and preferences, businesses can gain valuable insights into what drives purchasing decisions and tailor their strategies accordingly.

Action Point: Leverage data analytics tools and consumer research to gain a deeper understanding of your target audience and market trends. Track key metrics such as conversion rates, customer retention, and average order value to identify areas for improvement and optimization. By harnessing the power of data, you can make informed decisions that drive business growth and profitability.

In conclusion, while the classic jam experiment may seem like a trivial study, its implications for small business owners are anything but. By embracing the principles of simplicity, differentiation, customer-centricity, and data-driven decision-making, you can elevate your marketing efforts and unlock new opportunities for success in today’s competitive landscape.

- Personal Reflections: Lessons Learned in the Trenches

Reflecting on my own journey as a marketer, I’ve encountered countless instances where the principles elucidated by the jam experiment ring true. From refining product offerings to optimizing user experiences, the mantra of simplicity and focus has guided my strategic endeavors.

- Conclusion: The Art of Choice Architecture

In the labyrinth of consumer decision-making, the classic jam experiment serves as a beacon of clarity. By understanding the delicate interplay between choice and cognition, small business owners can craft more compelling narratives, simplify decision-making processes, and ultimately, carve out a distinct place in the hearts and minds of their customers.

People often think more means more. The more information we have, the more options to choose from, the better the final outcome and the happier we’ll be. Often, however, the opposite is true: the more choices we have, the higher our expectations become – and the more we worry about making the ‘wrong’ decision. Enter the ‘Paradox of Choice’.

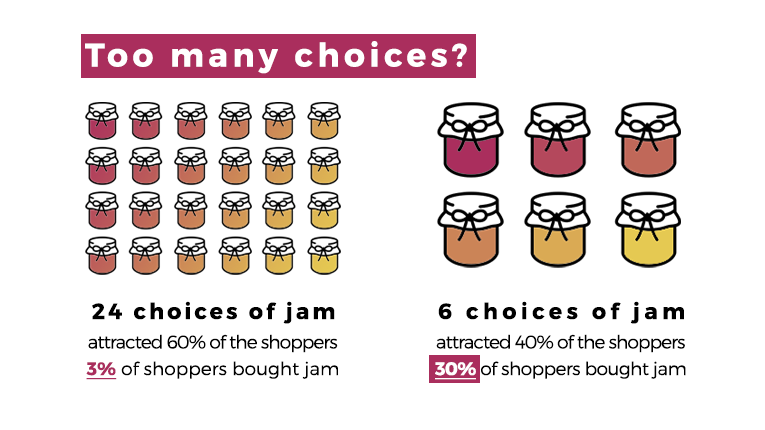

A classic experiment by Sheena Iyengar demonstrates this neatly:

Supermarket shoppers were presented with a variety of jam samples to try.

On day one, 6 different jams were available for tasting. On day two, 24 different jams were available for tasting.

Any guesses on which day resulted in more sales?

With fewer options, 40% of the shoppers tried the jams and 30% made a purchase.

With more options, 60% tried the jams, but just 3% made a purchase!

The conclusion: “choice is alluring but confusing”.

What does this mean? Keep things simple, limit options and keep testing.

More = difficult.

Know someone who'd find this interesting?

Topics covered

Join our newsletter

Want to get inside your customer's head? Get marketing and behavioural science tips in your inbox.

Latest articles

December 24, 2024

Boost Your Brand’s Credibility: Mastering Social Proof in Marketing

Stand Out or Fade Away: The Importance of Brand Distinctiveness

How Not To Plan

Written by : mark rowland.

Mark's been working in and interested in all things marketing since 2010.

Related Reads

14 February 2024

Unlocking Brand Perception: Strategies for Creating Lasting Impressions

14 January 2024

Signalling in Marketing: How to Make Your Brand Stand Out

7 September 2023

Building Distinctive Brand Assets

How Brands Grow – Byron Sharp

15 February 2018

Your Culture Is Your Brand

29 January 2018

When Logos Go Rogue

Stack the odds in your favour.

© 2015 - 2024 - Your Marketing Rules

Enjoy the rest of your Tuesday!

Want to get inside your customer’s head? Join our newsletter and get marketing and behavioural science tips in your inbox.

LevelUP Your Research

November 12, 2024

The Paradox of the Paradox of Choice

Discover how to navigate consumer choices effectively. Learn to leverage behavioral cues and refine ad targeting to enhance brand visibility and drive sales.

by Joel Rubinson

President at Rubinson Partners Inc

In the mid-2000s, Barry Schwartz wrote a book called the Paradox of Choice that drew marketers’ attention. It cited evidence that more choice was bad as it created stress and ultimately worse decision making on the part of consumers . Even worse, more choices led to less buying!

The central idea of the book was largely inspired by an experiment conducted by Dr. Sheena Iyengar, a professor at Columbia University, along with Mark Lepper from Stanford University. The experiment, often referred to as the "jam study," played a central role in illustrating the concept of choice overload, which Schwartz explores in his book.

The Jam Experiment

- Setting: The study took place in a supermarket, where Dr. Iyengar and her team set up a tasting booth offering samples of different types of jam.

- Two Conditions: In one version, shoppers could taste from 24 different jams, and in the other, they could taste from a smaller selection of 6 jams.

- Findings: When only 6 options were available, a significantly higher percentage made a purchase.

Surely any marketer would conclude that they have over-SKU-ed their brands based on this.

Only problem…this book is utterly wrong.

Theory is wrong.

Those who study behavioral economics know that when consumers are faced with too many choices, they use simplifying heuristics to make their choices manageable. Brand familiarity , what Amos Taversky called “elimination by aspects”, and satisficing are heuristics that consumers use to manage the effort needed to make a decision.

Evidence is questionable.

Notable meta-analysis by Peter Todd (integral to the Max Planck Institute for Behavior and Cognition) et al, published a review in 2010 of 50 studies on choice overload and concluded that the effect was not as robust or consistent as originally thought. They found that increased choice did not always reduce satisfaction or likelihood to choose, and the effects were often small or nonexistent.

I think the experiment was fundamentally flawed because, in real life, shoppers know the brands they are looking for so their heuristics work. In the jam experiment, everything was new to the shopper, replicating nothing in the real world. If you ever tried grocery shopping in a foreign country where the brands are mostly unfamiliar, you will see how much longer that takes. Again, the jam experiment represented something closer to that which meant nothing.

The marketplace is moving in a different direction.

Twenty years ago, a typical large supermarket carried 20-25,000 SKUs. Today it carries 35-40,000 SKUs. Then there is the dominance of Amazon where almost anything is available. If consumers hated choice and it stressed them out, why would retailers all be moving in the other direction?

My recommendations to marketers and researchers based on better behavioral economics than “the paradox of choice”:

- Don’t be afraid to add SKUs. This is a form of personalization. In addition, it might buy you extra facings in physical stores which is always a good thing.

- Help consumers navigate the blizzard of meaningless ads by making them more relevant through targeting. When you target the Movable Middle (those with a 20-80% probability of choosing your brand) you are helping people to decide in your favor as they are still considering alternatives of which you are one. The proof is that through 11 experiments, we found Movable Middles to be 2-23 times more responsive to advertising. That would only happen if the ads were relevant.

- Reinforce cues and be careful about changing them. The single biggest reason that the new packaging for Tropicana OJ was a disaster (-30% in sales) is that they messed up shoppers’ recognition heuristics. No shopper wants to spend 10 minutes buying orange juice!

- Shopper brains are Bayesian prediction engines so help them reach the right conclusions. The parent brand name, what you are next to on the shelf, package color and design, descriptors, the number and sentiment of reviews…these are all signals that the shopper brain ingests to predict what is their best choice (like Bayesian priors). I bet you could test an unknown coffee product, show it in a package design that connotes “premium” and strong taste, and placed next to Starbucks, give it some familiarity through branding and consumers could give you purchase interest, attribute ratings…the whole nine yards without telling them anything more about the new item.

- Marketing research lists. As implied in the book “Nudge”, marketing research survey design is a form of choice engineering. If you create lists that are too long, the brand of interest can get lost. Respondents will give you an answer but it is less likely to be the right one if the list is poorly constructed. If you want to accurately measure sub-category buying, balance the choices across sub-categories. For example, if you want to know if people recently bought a top (apparel), don’t give them one choice for tops and 10 choices for bottoms.

In a world where consumers are bombarded with choices, the key isn’t to reduce options but to help consumers navigate them effectively. By understanding behavioral cues and refining ad targeting strategies, marketers can turn a potential paradox into a powerful tool for driving attention to your brand and incremental sales.

Comments are moderated to ensure respect towards the author and to prevent spam or self-promotion. Your comment may be edited, rejected, or approved based on these criteria. By commenting, you accept these terms and take responsibility for your contributions.

Joel Rubinson

66 articles

The views, opinions, data, and methodologies expressed above are those of the contributor(s) and do not necessarily reflect or represent the official policies, positions, or beliefs of Greenbook.

More from Joel Rubinson

How to Improve Ad Attentiveness Measurement

Explore the hierarchy of advertising effects, from impressions to sales. Discover how consumer attentiveness and relevance drive effective marketing s...

August 13, 2024

Read article

Are You Using Synthetic Data for Analytics?

Explore the use of synthetic data to bridge the gap between sales and ad exposure data. Learn how it can enhance targeting and validate ad effectivene...

March 14, 2024

How Baseball Led Me to Marketing Analytics

Discover the power of Moneyballing marketing and revolutionize your outcomes by leveraging math over judgment for superior results.

January 9, 2024

Brand Differentiation: A Reality the Dirichlet Model Can’t Account For

Reevaluate marketing strategies and research approaches by challenging the Ehrenberg Bass Institute's claim on brand differentiation.

December 12, 2023

See all articles

Sign Up for Updates

Get content that matters, written by top insights industry experts, delivered right to your inbox.

67k+ subscribers

Weekly Newsletter

Greenbook Podcast

Event Updates

I agree to receive emails with insights-related content from Greenbook. I understand that I can manage my email preferences or unsubscribe at any time and that Greenbook protects my privacy under the General Data Protection Regulation.*

Get the latest updates from top market research, insights, and analytics experts delivered weekly to your inbox

Your guide for all things market research and consumer insights

Create a New Listing

Manage My Listing

Find Companies

by Specialty

by Location

Find Focus Group Facilities

Tech Showcases

GRIT Report

Expert Channels

Get in touch

For Suppliers

Marketing Services

Future List

Publish With Us

Privacy policy

Cookie policy

Terms of use

Copyright © 2024 New York AMA Communication Services, Inc. All rights reserved. 234 5th Avenue, 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10001 | Phone: (212) 849-2752

Choice paralysis and the fear of growing up

The Jam Experiment. In 2000, psychologists Sheena Iyengar from Columbia and Mark Lepper from Stanford published a study called, “When Choice is Demotivating: Can One Desire Too Much of a Good Thing?” This study is colloquially referred to as the Jam Experiment.

Essentially, Iyengar and Lepper set out to investigate whether or not the generally held belief that “the more choices the better” proved true in actuality. They suspected what they coined a “choice overload” would actually demotivate people to make a choice.

To test their claim, they set up tasting booths in an upscale grocery store that displayed either a limited (6) or an extensive (24) selection of different flavors of jam. They measured customers’ initial attraction to the tasting booth, as well as subsequent purchasing behavior.

After performing significance tests, they found that although customers were initially more attracted to the extensive choice booth, subsequent purchases at the limited selection booth beat out those at the extensive selection booth by a staggering 27%. In other words, humans are trash at making decisions when they are given too many choices.

And I am the worst of them all.

Ask my father, and he’ll tell you without hesitation that I spent most of high school complaining that my life was all routine and that I had no freedom to choose for myself. I saw our school system as a kind of trap that vacuumed the individualism right out of me. I said I couldn’t wait to graduate because then I’d have real agency to decide how my life looked.

As always, the grass is always greener, and I now sit paralyzed by the choice overload that is adulthood.

If I wanted to, I could drop out, buy a one-way ticket to Florence, and never come back. If I wanted to, I could spend every free second I had in the library until I’d written a three-part novel series from the perspective of the grass on Meyer Green. If I wanted to, I could shave my head. Buy a cat. Sell the cat. Buy another. Toss this computer in the garbage and never finish writing this article.

Now, most of these would be shit decisions, and I understand that. But the message stands — for probably the first time in my life, almost the entirety of it is up to me. You’d think I might have had this realization about a year and four months ago when I left for college. However, this university babies its freshmen similarly to how a parent does their children, and for a long time, I still felt like I had one telling me how my life should look.

This is not the case anymore. It may sound incredibly simple, but days here feel like the extensive choice booth. “Adult” life is what I thought I wanted — unbridled freedom to construct my life from scratch. This prospect, though, actually leaves me paralyzed by the infinite number of options I have. The choices I had to make in high school were significant, yes, but they were significantly more limited than they are now. There is no rubric for almost anything I do, and although this sounds exhilarating in theory, I end up sitting still, unsure of where to move. This is a lot of pressure for someone who still watches Spongebob.

For now, I’ll just try to buy some jam.

Contact Malia Mendez at mjm2000 ‘at’ stanford.edu .

Malia Mendez ’22 is the Vol. 260 Managing Editor of Arts & Life at The Stanford Daily. She is majoring in English with a concentration in Creative Writing, Prose track. Talk to her about Modernist poetry, ecofeminism or coming-of-age films at mmendez 'at' stanforddaily.com.

Login or create an account

Resources: Course Assignments

Assignment: Thinking and Intelligence—The Paradox of Choice

Psychology teaches us that choosing, perceiving, remembering, and other cognitive activities involve complex processes that compete for limited mental resources. The human brain is an amazing thing, but even when that brain is young and working well, it can reveal its limits by slipping up in surprising ways—like forgetting a decision made a few seconds ago just a few seconds later (choice blindness). Other interesting research provides some insight into how our brain’s manage decision-making. Do you think that making a choice puts big demands on our mental processing system? One line of research suggests that it does.

Let’s examine an experiment that was conducted at a small local grocery store by Sheena Iyengar, then a graduate student at Stanford University. She set up a table for tasting jam near the front of the store. Sometimes the table had 6 types of jam; other times there were 24 types.

Iyengar and her colleagues measured two things. First, which condition—6 jams or 24 jams—was more likely to get people to stop and taste the products? And second, which condition—6 jams or 24 jams—produced more sales of the jams that were sampled.

Take a guess before reading the answers that follow. What percentage of shoppers do you think stopped…

- when there were 24 jams on the table?

- when there were 6 jams on the table?

Now, just looking at the people who stopped and sampled some of the jam at the table, which condition led to better sales?

Take a guess before reading the answers that follow. What percentage of shoppers do you think bought jam…

Details of the Study

The experiment took place in a small but popular grocery store near the Stanford University campus, south of San Francisco, California. A tasting booth was set up in the store on two consecutive typical weekends. These customers were invited “come try our Wilkin and Sons jams.” This was a variety of jam that was typically sold in the store. However, the most popular flavors of the jam (e.g., strawberry and raspberry) were not included in the tasting booth set in order to encourage people to try something new. Shoppers were given a $1 off coupon to purchase a jam. The jams were priced between $4 and $6, before discount.

At different times, the booth offered either 6 types of jam or 24 types of jam. Jam was not sold at the tasting booth. If a person wanted to buy jam, he or she had to go to the shelves, find the jam from a set of 28 flavors of the Wilkin and Sons brand, as well as other jellies and jams regularly available. In other words, purchasing on of the jams required the shoppers to make the effort to find a particular jam on the shelves, just as they would on a typical shopping day.

The two experimental conditions in this study are:

- A table with 6 jars of jam

- A table with 24 jars of jam

A total of 242 customers walked near the booth when there were 24 jars on the table.

A total of 260 customers walked near the booth when there were 6 jars on the table.

Which table do you think had more customers stop and taste the jam? Take a look at the results below.

- 60% of the 242 customers (142) stopped at the 24 jam table

- 40% of the 260 customers (104) stopped at the 6 jam table

More people (and a higher percentage) stopped when there were 24 jars on the table than when there were only 6 jars. This suggests that lots of choices captures our attention and draws us in. Interestingly, customers actually tasted about the same number of jams in the two conditions: usually one or two jams.

The real test in this experiment is found in the amount of jam that was sold, either on the same day or within the week that the $1-off coupon was valid.

Which table do you think sold more jam? Take a look at the results below.

- Of the customers stopping at the 24 jam table, only 3% (4 customers) used the coupon to buy jam sometime in the following week.

- Of the customers stopping at the 6 jam table, 30% (34 customers) used the coupons to buy jam during the following week.

Statistically, there is a very strong difference between these two outcomes.

This result is called “the paradox of choice.” You might think that more options leads to greater likelihood that you will find something you like, and consequently you will be more likely to purchase something under those conditions. But Iyengar and Lepper found the opposite. An extensive number of items seemed to shut people down, making them far less likely to make a choice to purchase one item than when their list was very limited. The researchers studied a variety of other choice objects. For example, using a very different setting, they found similar results when people were offered a large or small variety of chocolates. And they found that students were far more likely to choose to write an optional extra-credit essay when offered only 6 topics to choose from than when they were offered 30 topics.

Why would people buy fewer products when they were given more choices?

Based on the research you just read about, describe Dr. Iyengar’s experiment with jam. First, identify the following:

- What are the two hypotheses in the experiment?

- What are the independent variables?

- What are the dependent variables?

Next, write a short description of the methods used to run this experiment. Then, write a paragraph analyzing the results. Spend time answering the question, “Why would people buy fewer products when they were given more choices?” Use your understanding of psychology and decision-making, as well as examples from your own life, to support your argument in explaining the paradox of choice.

CC licensed content, Original

- Thinking and Intelligenceu2014the Paradox of Choice. Authored by : Patrick Carroll for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

General Psychology Copyright © by OpenStax and Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Too Many Choices: A Problem That Can Paralyze

By Alina Tugend

- Feb. 26, 2010

TAKE my younger son to an ice cream parlor or restaurant if you really want to torture him. He has to make a choice, and that’s one thing he hates. Would chocolate chip or coffee chunk ice cream be better? The cheeseburger or the turkey wrap? His fear, he says, is that whatever he selects, the other option would have been better.

Gabriel is not alone in his agony. Although it has long been the common wisdom in our country that there is no such thing as too many choices, as psychologists and economists study the issue, they are concluding that an overload of options may actually paralyze people or push them into decisions that are against their own best interest.

There is a famous jam study (famous, at least, among those who research choice), that is often used to bolster this point. Sheena Iyengar, a professor of business at Columbia University and the author of “The Art of Choosing,” (Twelve) to be published next month, conducted the study in 1995.

In a California gourmet market, Professor Iyengar and her research assistants set up a booth of samples of Wilkin & Sons jams. Every few hours, they switched from offering a selection of 24 jams to a group of six jams. On average, customers tasted two jams, regardless of the size of the assortment, and each one received a coupon good for $1 off one Wilkin & Sons jam.

Here’s the interesting part. Sixty percent of customers were drawn to the large assortment, while only 40 percent stopped by the small one. But 30 percent of the people who had sampled from the small assortment decided to buy jam, while only 3 percent of those confronted with the two dozen jams purchased a jar.

That study “raised the hypothesis that the presence of choice might be appealing as a theory,” Professor Iyengar said last year, “but in reality, people might find more and more choice to actually be debilitating.”

Over the years, versions of the jam study have been conducted using all sorts of subjects, like chocolate and speed dating.

But Benjamin Scheibehenne, a research scientist at the University of Basel in Switzerland, said it might be too simple to conclude that too many choices are bad, just as it is wrong to assume that more choices are always better. It can depend on what information we’re being given as we make those choices, the type of expertise we have to rely on and how much importance we ascribe to each choice.

Mr. Scheibehenne recently co-wrote an analysis, to be published in October in The Journal of Consumer Research, examining dozens of studies about choices. One problem, he said, is separating the concept of choice overload from information overload.

In other words, he said, how much are people affected by the number of choices and “how much from the lack of information or any prior understanding of the options?”

I know this from experience. A while back, I spent a great deal of time trying to decide which company should provide our Internet, phone and television cable service. I was looking at only two alternatives, but the options — cost, length of contract, present and future discounts, quality of service — made the decision inordinately difficult.

This was not only because I wanted to get the best deal, but because the information from the companies was overly complicated and vague. I suspected that both companies were less interested in my welfare than in getting my money — and I didn’t want to be a sucker. This was a problem partly of choice overload — too many options — but also of poor information.

Research also shows that an excess of choices often leads us to be less, not more, satisfied once we actually decide. There’s often that nagging feeling we could have done better.

Understanding how we choose could guide employers and policy makers in helping us make better decisions. For example, most of us know that it’s a wise decision to save in a 401(k). But studies have shown that if more fund options are offered, fewer people participate. And the highest participation rates are among those employees who are automatically enrolled in their company’s 401(k)’s unless they actively choose not to.

This is a case where offering a default option of opting in, rather than opting out (as many have suggested with organ donations as well) doesn’t take away choice but guides us to make better ones, according to Richard H. Thaler, an economics professor at the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago, and Cass R. Sunstein, a professor at Chicago’s law school, who are the authors of “Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness” (Yale University Press, 2008). Making choices can be most difficult in the area of health. While we don’t want to go back to the days when doctors unilaterally determined what was best, there may be ways of changing policy so that families are not forced to make unbearable choices.

Professor Iyengar and some colleagues compared how American and French families coped after making the heart-wrenching decision to withdraw life-sustaining treatment from an infant. In the United States, parents must make the decision to end the treatment, while in France, the doctors decide, unless explicitly challenged by the parents.

This contrast in the “choosing experience,” she wrote, made a difference in how the families later coped with their decisions.

French families weren’t as angry or confused about what had happened, and focused much less on how things might have been or should have been than the American parents.

It is important to note that no one is suggesting that parents be kept out of the loop in such a crucial matter. Rather, the choice, as Professor Iyengar said, was between “informed choosers” and “informed nonchoosers.”

Since, fortunately, most of our decisions are less weighty, one way to tackle the choice problem is to become more comfortable with the idea of “good enough,” said Barry Schwartz, a professor of psychology at Swarthmore College and author of “The Paradox of Choice” (Ecco, 2003).

Seeking the perfect choice, even in big decisions like colleges, “is a recipe for misery,” Professor Schwartz said.

This concept may even extend to, yes, marriage. Lori Gottlieb is the author of “Marry Him: The Case for Settling for Mr. Good Enough” (Dutton Adult, 2010). Too many women — her book focused on women — “think I have to pick just the right one. Instead of wondering, ‘Am I happy?’ they wonder, ‘Is this the best I can do?’ ”

And even though we now have the capacity, via the Internet, to research choices endlessly, it doesn’t mean we should. When looking, for example, for a new camera or a hotel, Professor Schwartz said, limit yourself to three Web sites. As Mr. Scheibehenne said: “It is not clear that more choice gives you more freedom. It could decrease our freedom if we spend so much time trying to make choices.”

E-mail: [email protected]

In 2000, Professor Sheena Iyengar from Columbia University famously conducted the ‘jam study’ as an exploration of choice and decision making. In the study, Iyengar and her researchers first displayed 24 jams in a busy supermarket, encouraging free tasting. This abundance of choice saw 60% of customers stopping and tasting the jam, but only 3% making a purchase.

Next, the researchers set up the display with 6 jam jars. This time there were fewer customers stopping, only 40%, but the actual purchases went up tenfold, to 30%. This study became a central example in Barry Schwartz's 2004 book, The Paradox of Choice.

The paradox of choice is a phenomenon where an abundance of options can counterintuitively lead to less happiness, less satisfaction, and hamper the ability to make a decision.

BEHIND THE PARADOX.

Some of the reasons why more choices might result in lower conversion rates include:

More obvious Opportunity Cost : when presented with options, the loss of the choice you didn’t make will potentially be heightened in your mind. Also known as ‘FOMO’ or the fear of missing out.

Decision fatigue and overwhelm , with an understanding of thinking fast and slow : where every conscious decision you make has a cognitive cost, making such decisions can be exhausting.

AN INFLUENTIAL MODEL.

The paradox of choice model made a significant impact at the time — Schwartz’s book became a bestseller and its premise was endorsed by many credible sources. Since 2004, modern consumers have only been more inundated with choices — from media, online shopping, and don’t get me started on the rows and rows of toothpaste in the supermarket! Which makes the backlash against the model all the more surprising.

THE BACKLASH AGAINST IT.

This backlash came to the fore in 2010 with a meta-analysis by Benjamin Scheibehenne. His results are often held up to be a straight rejection of Iyengar’s research, revealing difficulties replicating the findings of the jam study, given that he identified an average nil effect. Digging deeper, the nil average hides the fact that the actual results were quite varied — with choice sometimes increasing conversion rates, and other times minimising it.

CHOICE OVERLOAD vs INFORMATION OVERLOAD.

One distinction Scheibehenne made in trying to understand his findings was the difference between ‘choice overload’ versus ‘information overload’ . Indeed Schwartz, revisiting his work, pointed out that the paradox of choice does not apply when a person knows a domain well and can be mitigated with an effective presentation of the choices.

MEANINGFUL CHOICE AS A FACTOR.

Others have claimed that the reduced conversion rate arises from the ‘lack of meaningful choice’ , rather than choice itself. And some researchers have since pointed to additional moderating factors, including the:

Difficulty of the decision task: how much work is involved in making a decision.

Complexity of the choice set: how easy is it to make comparisons.

Level of uncertainty : the ability for a consumer to evaluate options or be clear on their preference.

Decision goal: whether it's to minimise cognitive load or find the best option.

SO HOW USEFUL IS THIS MODEL?

Where does the debate leave you in deciding choice sets in your marketing campaign, product strategy, or simply striving for a happier life? Well, it’s complicated. Dare we remind you that the Map is Not the Territory ?

The truth is that the paradox of choice model has its uses but also has clear limitations. When applying it, use experimentation methods such as Split Testing , to identify the impact on your specific challenge and context. Also, consider some of the above factors in deciding whether the choice you might be providing is a blocker or a benefit. See the Actionable Takeaways below for more.

IN YOUR LATTICEWORK.

This model is often viewed as part of broader Behavioural Economics, so is informed by Fast and Slow Thinking . As mentioned, it has also been explained by the Opportunity Cost.

In designing for user interaction, whether it be in delivering a UX, product range or anything, consider addressing this potential challenge with models such as Occam's Razor to simplify; the EAST Framework to design Nudges; and/or Anchoring to frame and influence a user experience.

Reduce the amount of choice.

Where appropriate, experiment with reducing options.

Provide clear comparisons or implications for choices.

Consider how to present key information to facilitate an easier choice between multiple options.

Provide clear and low friction pathways.

Use a strong and directed call to action; a personalised pathway; social or system based recommendations; or other strategies to highlight a simple decision path for the user.

Provide social proof.

Leverage people’s opinions through likes, shares or votes etc, to indicate what is being recommended by the crowd — this is particularly effective when the ‘crowd’ in question has a meaningful connection with the user.

Organise and present effectively.

Consider how you categorise, what you present where, and how you direct attention to support easy decision making. Refer to the EAST framework for this and the previous point.

In your own decision marking, strategically limit your own choice.

You might do this by creating rules that you apply to non-essential issues (e.g. Steve Jobs and Barack Obama famously wearing the same clothes repeatedly); identify what decisions increase anxiety and ‘paralysis’ and consider how to reduce the choice in them; consider focusing on ‘good enough’ to help let go of the opportunity cost.

Experiment and test.

Apply the paradox of choice as a principle rather than a fixed rule. Split test and experiment in your context to judge the impact.

Understand & work with your brain.

Fast. Actionable. Free.

Apply product design techniques.

As foreshadowed in the overview section above, there are a few sticking points with this model. Sticking points… jam… see what I did there? Yeah, okay, sorry about that.

Firstly, in 2010 after finding no significant variance in ten consecutive choice based experiments, Scheibehenne’s team embarked on their meta-analysis of the research behind the paradox of choice to that point. The average of those studies did not provide evidence that extra choice impacted decisions in either direction. However, there were quite stark results to either direction, adding more complexity and leaving more room for debate. Indeed this recent review of the research concluded that the area needed more study and that the ‘jury is out’.

Schwartz himself has not been shy in responding to criticisms . At once acknowledging the mixed results, he also maintains that the results are part of the scientific method. Schwartz explains: “the final story on the “paradox of choice” has yet to be written. But to me, it is a beautiful example of how science works when it is doing what it should. An important idea goes from “unthinkable” to “commonly assumed.” Then, further work reveals that there are limits to this idea. Over time, we develop generalizations that are appropriately qualified and contextualized. People understand something they didn’t before, and spend their time and mental effort in ways that are more productive and satisfying than was the case before.”

Procter & Gamble.

A popular example of the paradox of choice comes from Procter & Gamble. They decreased the number of Head & Shoulders varieties, their shampoo brand, from 26 options to 15. This resulted in more sales and 10% more revenue.

Do you even remember Yahoo?

Can you cast your mind back to the UX of the once-popular Yahoo — for those of you not old enough to remember, Yahoo was once a giant of the internet with a ‘portal’ styled homepage much akin to a busy magazine layout. Now compare that to the option that beat them — Google.

Here at ModelThinkers.

This model was in our minds when we designed ModelThinkers . We are very aware that people might find the growing number of mental models on our site overwhelming and freeze as a result. As a result, we’re working hard to mitigate this through the categorisation and UX design, presenting stories and clusters of models via the blog to help frame and connect them, and drip-feeding the models via our free weekly newsletter and the ‘model of the week.’

The paradox of choice sits within the behavioural economics domain, as it speaks to the potential irrationality of how you make decisions.

Use the following examples of connected and complementary models to weave the paradox of choice into your broader latticework of mental models. Alternatively, discover your own connections by exploring the category list above.

Connected models:

Thinking fast and slow: in terms of understanding the automatic pilot of most decisions.

Opportunity cost: in the more apparent cost when faced with an abundance of choice.

Complementary models:

Map vs territory: to understand the potential limitations and usefulness of this model.

EAST framework: to help guide choices through nudges.

Anchoring heuristic: in framing a consumer’s attitude and choice.

Split testing: an important model to test out options given the variations in findings behind these choice experiments.

The history of the paradox of choice and its detractors have been described in the overview section because they were pertinent to understanding and applying this model.

Explore the original Jam study findings are here , and although she did not receive as much fame as Schwartz, Professor Iyengar continues to work in this field — see Iyengar’s website and latest research here . You can view Barry Schwartz's original book called The Paradox of Choice here , and his 2005 Ted talk here .

Oops, That’s Members’ Only!

Fortunately, it only costs US$5/month to Join ModelThinkers and access everything so that you can rapidly discover, learn, and apply the world’s most powerful ideas.

ModelThinkers membership at a glance:

“Yeah, we hate pop ups too. But we wanted to let you know that, with ModelThinkers, we’re making it easier for you to adapt, innovate and create value. We hope you’ll join us and the growing community of ModelThinkers today.”

You Might Also Like:

Subscribe to Thinking Hacks, our free weekly newsletter now.

Subscribe now and download this practical guide to transform your thinking, plus recieve one short, powerful and actionable idea in your inbox each month.

- Unlock everything, including toolkits

- Save and personalise models

- Learn models with simple memory hacks

- Join the ModelThinkers community

- All that and more for only US$5/month!

--> Plan Monthly (US$ 8 /month) ANNUALLY (US$ 60 /year) Name E-Mail Address Password Confirm Password Credit card number Expiration Month --> Expiration Month Expiration Year CVV Coupon code Register Sign up to ModelThinkers (very short) weekly update & thinking tips. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book.

Login to Your Account

Remember me

forgot your password? click here

Forgot Password?

You can reset your password here.

Create a New Model Edit Your Model

Read a new book, discover a new idea, or watch an amazing talk build your digital brain by capturing the main models and takeaways here. all you need is a title, but you can also add an image, description and even use our categories if you'd like. view them from the my latticework section . models you create are not public and are only viewable by you..

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Jan 19, 2015 · If you’re not familiar with the original Jam Study, it’s here. Basically, the study, which was conducted at upscale Bay-area supermarket Draeger’s Market by psychologists Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper, found that consumers were 10 times more likely to purchase jam on display when the number of jams available was reduced from 24 to 6.

300 varieties of jam. In addition, because of the regular presence of tasting booths at this store, shoppers are frequently offered sample tastes of the enormous array of available products. As a result, this store provided a particularly conducive environment in which a naturalistic experiment that

This theory was created as a result of the Jam study, one of the most famous experiments in consumer psychology ever undertaken, conducted at the upscale Bay-area supermarket Draeger’s Market by psychologists Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper. According to the design of the experiment, on one day, the store’s customers were offered 24 ...

Feb 17, 2018 · One seminal study that sheds light on this intricate web of decision-making is the classic jam experiment conducted by Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper. Setting the Stage: The Jam Dilemma. Picture this: you stroll into a grocery store, greeted by rows of colorful jars filled with delectable jams. The choices seem endless, yet daunting.

Nov 12, 2024 · The experiment, often referred to as the "jam study," played a central role in illustrating the concept of choice overload, which Schwartz explores in his book. The Jam Experiment. Setting: The study took place in a supermarket, where Dr. Iyengar and her team set up a tasting booth offering samples of different types of jam.

Jul 29, 2023 · A unique social experiment is about to unfold, teaching us how our purchasing decisions can be influenced by the amount of choice presented. The Classic Jam Study: A Tale of Six vs. Twenty-Four

Feb 3, 2020 · The Jam Experiment. In 2000, psychologists Sheena Iyengar from Columbia and Mark Lepper from Stanford published a study called, “When Choice is Demotivating: Can One Desire Too Much of a Good ...

Let’s examine an experiment that was conducted at a small local grocery store by Sheena Iyengar, then a graduate student at Stanford University. She set up a table for tasting jam near the front of the store. Sometimes the table had 6 types of jam; other times there were 24 types. Iyengar and her colleagues measured two things.

Feb 27, 2010 · The salad options at a Woolworths supermarket in Sydney, Australia. Too many choices can trouble consumers. ... and each one received a coupon good for $1 off one Wilkin & Sons jam.

In 2000, Professor Sheena Iyengar from Columbia University famously conducted the ‘jam study’ as an exploration of choice and decision making. In the study, Iyengar and her researchers first displayed 24 jams in a busy supermarket, encouraging free tasting. This abundance of choice saw 60% of customers stopping and tasting the jam, but only 3% making a purchase. Next, the ...