- 20 Most Unethical Experiments in Psychology

Humanity often pays a high price for progress and understanding — at least, that seems to be the case in many famous psychological experiments. Human experimentation is a very interesting topic in the world of human psychology. While some famous experiments in psychology have left test subjects temporarily distressed, others have left their participants with life-long psychological issues . In either case, it’s easy to ask the question: “What’s ethical when it comes to science?” Then there are the experiments that involve children, animals, and test subjects who are unaware they’re being experimented on. How far is too far, if the result means a better understanding of the human mind and behavior ? We think we’ve found 20 answers to that question with our list of the most unethical experiments in psychology .

Emma Eckstein

Electroshock Therapy on Children

Operation Midnight Climax

The Monster Study

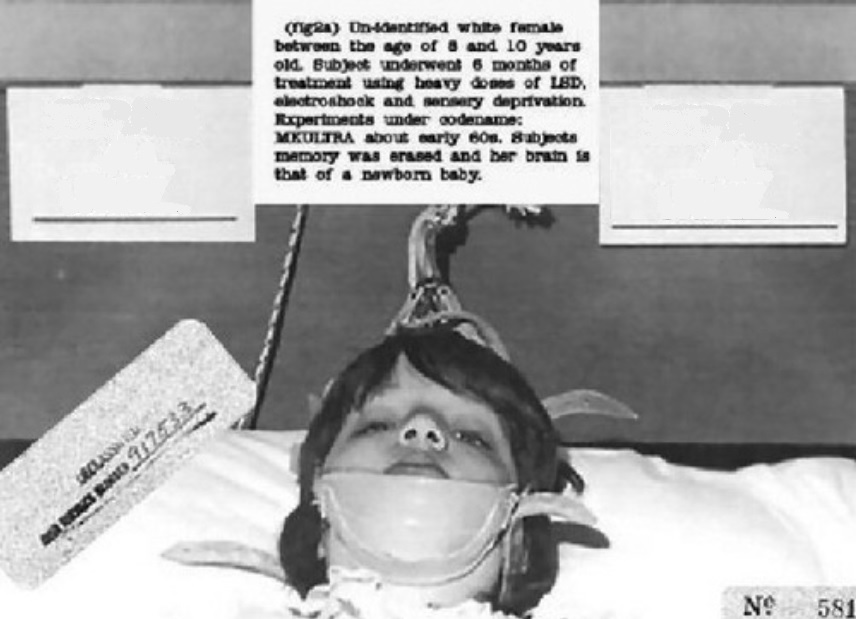

Project MKUltra

The Aversion Project

Unnecessary Sexual Reassignment

Stanford Prison Experiment

Milgram Experiment

The Monkey Drug Trials

Featured Programs

Facial expressions experiment.

Little Albert

Bobo Doll Experiment

The Pit of Despair

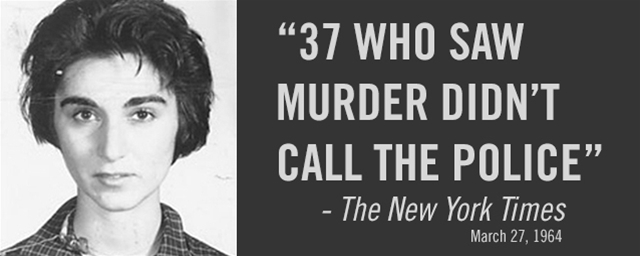

The Bystander Effect

Learned Helplessness Experiment

Racism Among Elementary School Students

UCLA Schizophrenia Experiments

The Good Samaritan Experiment

Robbers Cave Experiment

Related Resources:

- What Careers are in Experimental Psychology?

- What is Experimental Psychology?

- The 25 Most Influential Psychological Experiments in History

- 5 Best Online Ph.D. Marriage and Family Counseling Programs

- Top 5 Online Doctorate in Educational Psychology

- 5 Best Online Ph.D. in Industrial and Organizational Psychology Programs

- Top 10 Online Master’s in Forensic Psychology

- 10 Most Affordable Counseling Psychology Online Programs

- 10 Most Affordable Online Industrial Organizational Psychology Programs

- 10 Most Affordable Online Developmental Psychology Online Programs

- 15 Most Affordable Online Sport Psychology Programs

- 10 Most Affordable School Psychology Online Degree Programs

- Top 50 Online Psychology Master’s Degree Programs

- Top 25 Online Master’s in Educational Psychology

- Top 25 Online Master’s in Industrial/Organizational Psychology

- Top 10 Most Affordable Online Master’s in Clinical Psychology Degree Programs

- Top 6 Most Affordable Online PhD/PsyD Programs in Clinical Psychology

- 50 Great Small Colleges for a Bachelor’s in Psychology

- 50 Most Innovative University Psychology Departments

- The 30 Most Influential Cognitive Psychologists Alive Today

- Top 30 Affordable Online Psychology Degree Programs

- 30 Most Influential Neuroscientists

- Top 40 Websites for Psychology Students and Professionals

- Top 30 Psychology Blogs

- 25 Celebrities With Animal Phobias

- Your Phobias Illustrated (Infographic)

- 15 Inspiring TED Talks on Overcoming Challenges

- 10 Fascinating Facts About the Psychology of Color

- 15 Scariest Mental Disorders of All Time

- 15 Things to Know About Mental Disorders in Animals

- 13 Most Deranged Serial Killers of All Time

Site Information

- About Online Psychology Degree Guide

- General Categories

- Mental Health

- IQ and Intelligence

- Bipolar Disorder

Ethical Violations in Psychology: Consequences and Prevention Strategies

From the sacred trust between therapist and client to the integrity of groundbreaking research, the field of psychology is built upon a foundation of unwavering ethical standards – a foundation that, when compromised, can lead to devastating consequences. The realm of psychology, with its intricate web of human interactions and delicate balance of power, demands an unwavering commitment to ethical conduct. It’s a field where the stakes are high, and the potential for harm is ever-present.

Imagine, for a moment, the vulnerability of a client baring their soul to a therapist, or the trust placed in researchers to uncover truths about the human mind. These scenarios underscore the critical importance of ethics in psychological practice. Without a strong ethical framework, the entire edifice of psychology could crumble, leaving a trail of broken trust and shattered lives in its wake.

The journey towards establishing ethical guidelines in psychology has been long and, at times, tumultuous. From the early days of Freudian psychoanalysis, where boundaries were often blurred, to the shocking revelations of unethical experiments in the mid-20th century, the field has grappled with defining and refining its moral compass. Today, we stand on the shoulders of those who fought to establish clear ethical boundaries, yet the battle is far from over.

The Ethical Minefield: Where Violations Commonly Occur

As we delve deeper into the ethical landscape of psychology, it becomes apparent that certain areas are particularly prone to violations. These ethical hotspots often arise where the lines between professional and personal blur, where the allure of groundbreaking research tempts shortcuts, or where the complexities of human interaction challenge even the most well-intentioned practitioners.

One of the most sacred tenets of psychology is confidentiality. The trust that clients place in their therapists is paramount, and any breach can have far-reaching consequences. Yet, in an age of digital records and interconnected systems, maintaining absolute confidentiality has become increasingly challenging. From inadvertent disclosures to deliberate breaches, ethical issues in psychology often revolve around this fundamental principle.

Another treacherous terrain is that of dual relationships and boundary violations. The power dynamic between a psychologist and their client or research subject is inherently unbalanced, and maintaining appropriate boundaries is crucial. However, the line can sometimes become blurred, especially in small communities or specialized fields where paths frequently cross outside the professional setting.

Informed consent, a cornerstone of ethical practice, is another area ripe for potential violations. In the rush to advance knowledge or treat patients, practitioners may sometimes fail to fully explain the risks and implications of treatment or research participation. This oversight, whether intentional or not, undermines the autonomy and dignity of those involved.

When Ethics Take a Back Seat: Types of Violations

Let’s take a closer look at some of the most common ethical violations that plague the field of psychology. These transgressions range from the subtle to the egregious, but all have the potential to cause significant harm.

Confidentiality breaches, as mentioned earlier, can take many forms. It might be as simple as a therapist discussing a client’s case with a colleague without proper anonymization, or as severe as selling client data to third parties. In an era where information is currency, the temptation to misuse confidential data is ever-present.

Dual relationships and boundary violations occur when the professional line is crossed. This could involve a therapist entering into a business partnership with a client, or worse, engaging in a romantic relationship. Such violations exploit the vulnerable position of the client and can lead to lasting psychological damage.

Informed consent issues arise when participants in research or therapy are not fully aware of what they’re agreeing to. This could involve withholding crucial information about potential risks or using deception in research without proper justification and debriefing. Ethical issues in psychological research often stem from a failure to obtain truly informed consent.

Competence and scope of practice violations occur when psychologists operate outside their areas of expertise. This might involve a therapist trained in adult psychology attempting to treat complex childhood disorders, or a researcher venturing into unfamiliar territory without proper preparation or supervision.

Perhaps one of the most damaging forms of ethical violation is research misconduct and data manipulation. The pressure to publish, secure funding, or make groundbreaking discoveries can sometimes lead researchers down a dark path. Fabricating data, selectively reporting results, or manipulating statistics not only undermines the integrity of the field but can also lead to real-world harm if faulty conclusions inform policy or treatment decisions.

The Ripple Effect: Consequences of Ethical Breaches

When ethical standards are compromised in psychology, the consequences can be far-reaching and devastating. The impact reverberates through individual lives, professional careers, and the entire field of psychology.

For clients and research participants, the effects of ethical violations can be profound and long-lasting. A breach of confidentiality might lead to personal or professional repercussions, damaged relationships, or even legal troubles. Boundary violations in therapy can leave clients feeling betrayed, confused, and unable to trust future mental health professionals. Participants in unethical research may suffer physical or psychological harm, or make life decisions based on faulty information.

The professional repercussions for psychologists who violate ethical standards are severe. Depending on the nature and severity of the violation, consequences can range from formal reprimands to loss of licensure and the end of a career. The conflict of interest in psychology can lead to situations where a practitioner’s judgment is compromised, often with dire professional consequences.

Legal consequences and malpractice suits are a very real possibility in cases of serious ethical violations. Psychologists may find themselves facing civil lawsuits or even criminal charges, depending on the nature of their actions. The financial and emotional toll of such legal battles can be enormous, even if the practitioner is ultimately exonerated.

Perhaps most insidiously, ethical violations damage the reputation of the entire field of psychology. Each high-profile case of misconduct erodes public trust in psychological research and practice. This can lead to decreased funding for important research, skepticism towards mental health treatment, and a general devaluation of psychological expertise in public discourse.

Cautionary Tales: Notable Ethical Violations in Psychology

The annals of psychology are unfortunately replete with examples of ethical violations that serve as stark reminders of the importance of maintaining rigorous ethical standards. These case studies not only illustrate the potential for harm but also provide valuable lessons for future practitioners and researchers.

One of the most infamous examples is the Stanford Prison Experiment, conducted by Philip Zimbardo in 1971. This study, which aimed to investigate the psychological effects of perceived power in a simulated prison environment, quickly spiraled out of control. Participants playing the roles of guards became abusive, while those playing prisoners experienced severe psychological distress. The experiment was terminated early, but not before raising serious questions about the ethics of placing participants in potentially harmful situations for the sake of research.

Another shocking revelation came with the Hoffman Report in 2015, which exposed the American Psychological Association’s involvement in the U.S. government’s torture program. This report revealed how some psychologists had colluded with the Department of Defense to justify enhanced interrogation techniques, fundamentally violating the principle of “do no harm” that underpins the profession.

Unethical psychology experiments like these serve as stark reminders of the potential for harm when ethical boundaries are crossed. They underscore the need for constant vigilance and robust ethical frameworks in psychological research and practice.

Therapist-patient sexual relationships represent one of the most egregious ethical violations in clinical practice. Despite clear prohibitions, cases of sexual involvement between therapists and clients continue to occur, often with devastating consequences for the vulnerable clients involved. These cases not only violate professional ethics but can also result in criminal charges.

In the realm of research, falsification of data in high-profile studies has repeatedly rocked the foundations of psychological science. One notable example is the case of Diederik Stapel, a Dutch social psychologist who was found to have fabricated or manipulated data in dozens of published studies. Such cases of research misconduct not only damage individual careers but also undermine the credibility of psychological research as a whole.

Safeguarding Ethics: Prevention Strategies

Given the severe consequences of ethical violations, it’s crucial to implement robust prevention strategies. These strategies must be comprehensive, addressing both individual and systemic factors that contribute to ethical lapses.

Ongoing ethics education and training form the foundation of ethical practice. Ethics in psychology is not a static field; as new technologies and research methodologies emerge, so do new ethical challenges. Regular training helps psychologists stay abreast of evolving ethical standards and provides a forum for discussing complex ethical dilemmas.

Implementing robust ethical decision-making models can provide a framework for navigating difficult situations. These models encourage practitioners to consider multiple perspectives, weigh potential consequences, and consult relevant ethical guidelines before making decisions.

Peer consultation and supervision play a crucial role in maintaining ethical standards. By discussing challenging cases or research dilemmas with colleagues, psychologists can gain valuable insights and avoid potential pitfalls. This collaborative approach also helps to create a culture of ethical awareness within the profession.

Institutional review boards (IRBs) and ethics committees serve as crucial gatekeepers, particularly in research settings. These bodies review proposed studies to ensure they meet ethical standards, protecting the rights and welfare of research participants. Similarly, professional organizations often have ethics committees that can provide guidance and, when necessary, investigate ethical complaints.

Perhaps most importantly, cultivating self-reflection and personal awareness is essential for ethical practice. Psychologists must be willing to examine their own biases, motivations, and potential conflicts of interest. This ongoing process of self-examination helps to prevent unconscious ethical lapses and fosters a deep commitment to ethical conduct.

Navigating the Future: Ethical Challenges in Modern Psychology

As psychology evolves and adapts to a rapidly changing world, new ethical challenges continue to emerge. These challenges require ongoing discussion, research, and policy development to ensure that ethical standards keep pace with technological and social changes.

Telepsychology and online therapy have exploded in popularity, particularly in the wake of global events like the COVID-19 pandemic. While these modalities offer increased access to mental health services, they also raise new ethical considerations. Issues of privacy, confidentiality, and the ability to respond to crises in remote settings are just a few of the challenges that need to be addressed.

Cultural competence and diversity issues have come to the forefront of ethical discussions in psychology. As our understanding of cultural differences and systemic inequalities deepens, psychologists must grapple with how to provide culturally sensitive and equitable care. This includes acknowledging and addressing biases in research methodologies and clinical practices that have historically marginalized certain groups.

The pervasive use of social media has blurred the lines between personal and professional lives, creating new ethical dilemmas for psychologists. Maintaining appropriate boundaries with clients in the age of Facebook and Twitter requires careful consideration and clear guidelines.

Artificial intelligence and big data analytics offer exciting possibilities for psychological research and practice, but they also raise significant ethical concerns. Issues of data privacy, algorithmic bias, and the potential for AI to replace human judgment in clinical settings are just some of the challenges that need to be addressed.

The Ethical Imperative: A Call to Action

As we’ve explored the landscape of ethical violations in psychology, from the devastating consequences to the strategies for prevention, one thing becomes abundantly clear: maintaining ethical standards is not just a professional obligation, but a moral imperative.

The 5 ethical principles in psychology – beneficence and nonmaleficence, fidelity and responsibility, integrity, justice, and respect for people’s rights and dignity – serve as a guiding light. They remind us that at the heart of psychological practice and research lies a fundamental commitment to human welfare and dignity.

Yet, as we’ve seen, these principles are not self-enforcing. They require constant vigilance, ongoing education, and a willingness to engage in difficult conversations. The ethical challenges facing psychology are not static; they evolve with our changing society and technological landscape. As such, our approach to ethics must be dynamic and proactive.

For individual psychologists, this means committing to lifelong learning about ethical issues, seeking out supervision and consultation when faced with ethical dilemmas, and cultivating a deep sense of personal and professional integrity. It means being willing to speak up when ethical violations are observed, even when doing so is uncomfortable or potentially costly.

For the field as a whole, it means fostering a culture where ethical conduct is not just expected, but celebrated. It means supporting robust systems of oversight and accountability, while also providing resources and support for psychologists grappling with ethical challenges. It means engaging in ongoing research and dialogue about emerging ethical issues, ensuring that our ethical frameworks remain relevant and effective.

The consequences of ethical violations in psychology are too severe to ignore. From the individual client who suffers a breach of trust, to the broader public whose faith in psychological science is shaken by research misconduct, the stakes are immensely high. Yet, with each ethical challenge we face and overcome, we strengthen the foundation of our field.

As we look to the future, let us remember that ethics in psychology is not a burden, but a privilege. It is the means by which we honor the trust placed in us by our clients, our research participants, and society at large. It is how we ensure that our work truly serves the greater good, advancing our understanding of the human mind and behavior while respecting the dignity and rights of every individual.

In the end, ethical conduct in psychology is not just about avoiding harm or meeting professional standards. It’s about striving for excellence, about pushing the boundaries of our knowledge and practice in ways that uplift and empower. It’s about realizing the full potential of psychology as a force for positive change in the world.

So let this be a call to action for all psychologists, present and future. Let us commit ourselves anew to the highest ethical standards, not out of fear of consequences, but out of a genuine desire to do what is right. Let us approach each day, each client, each research project with a renewed sense of ethical purpose. For in doing so, we not only protect our field – we elevate it.

References:

1. American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. Washington, DC: Author.

2. Barnett, J. E., & Johnson, W. B. (2015). Ethics desk reference for counselors. John Wiley & Sons.

3. Fisher, C. B. (2016). Decoding the ethics code: A practical guide for psychologists. Sage Publications.

4. Hoffman, D. H., Carter, D. J., Viglucci Lopez, C. R., Benzmiller, H. L., Guo, A. X., Latifi, S. Y., & Craig, D. C. (2015). Report to the special committee of the board of directors of the American Psychological Association: Independent review relating to APA ethics guidelines, national security interrogations, and torture. Chicago, IL: Sidley Austin LLP.

5. Knapp, S., & VandeCreek, L. (2012). Practical ethics for psychologists: A positive approach. American Psychological Association.

6. Pope, K. S., & Vasquez, M. J. (2016). Ethics in psychotherapy and counseling: A practical guide. John Wiley & Sons.

7. Teo, T. (2015). Critical psychology: A geography of intellectual engagement and resistance. American Psychologist, 70(3), 243-254.

8. Zimbardo, P. G. (2007). The Lucifer effect: Understanding how good people turn evil. Random House.

Was this article helpful?

Would you like to add any comments (optional), leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Related Resources

Psychology Pre-Med: Bridging Mind and Medicine in Your Medical Journey

NJ Psychology License: A Comprehensive Guide to Becoming Licensed in…

Psychology and Pre-Law: Building a Strong Foundation for Legal Studies

Professional Psychology Research and Practice: Bridging Theory and Application

Psychological Principles: Foundations of Human Behavior and Mental Processes

Psychological Science vs Psychology: Key Differences and Similarities

Informed Consent in Psychology: Ethical Foundations and Practical Applications

Pseudoscience in Psychology: Separating Fact from Fiction in Mental Health

NYS Psychology License: A Comprehensive Guide to Certification and Practice

Implicit Bias in Psychology: Definition, Impact, and Strategies for Mitigation

Ethical Considerations In Psychology Research

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Ethics refers to the correct rules of conduct necessary when carrying out research. We have a moral responsibility to protect research participants from harm.

However important the issue under investigation, psychologists must remember that they have a duty to respect the rights and dignity of research participants. This means that they must abide by certain moral principles and rules of conduct.

What are Ethical Guidelines?

In Britain, ethical guidelines for research are published by the British Psychological Society, and in America, by the American Psychological Association. The purpose of these codes of conduct is to protect research participants, the reputation of psychology, and psychologists themselves.

Moral issues rarely yield a simple, unambiguous, right or wrong answer. It is, therefore, often a matter of judgment whether the research is justified or not.

For example, it might be that a study causes psychological or physical discomfort to participants; maybe they suffer pain or perhaps even come to serious harm.

On the other hand, the investigation could lead to discoveries that benefit the participants themselves or even have the potential to increase the sum of human happiness.

Rosenthal and Rosnow (1984) also discuss the potential costs of failing to carry out certain research. Who is to weigh up these costs and benefits? Who is to judge whether the ends justify the means?

Finally, if you are ever in doubt as to whether research is ethical or not, it is worthwhile remembering that if there is a conflict of interest between the participants and the researcher, it is the interests of the subjects that should take priority.

Studies must now undergo an extensive review by an institutional review board (US) or ethics committee (UK) before they are implemented. All UK research requires ethical approval by one or more of the following:

- Department Ethics Committee (DEC) : for most routine research.

- Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) : for non-routine research.

- External Ethics Committee (EEC) : for research that s externally regulated (e.g., NHS research).

Committees review proposals to assess if the potential benefits of the research are justifiable in light of the possible risk of physical or psychological harm.

These committees may request researchers make changes to the study’s design or procedure or, in extreme cases, deny approval of the study altogether.

The British Psychological Society (BPS) and American Psychological Association (APA) have issued a code of ethics in psychology that provides guidelines for conducting research. Some of the more important ethical issues are as follows:

Informed Consent

Before the study begins, the researcher must outline to the participants what the research is about and then ask for their consent (i.e., permission) to participate.

An adult (18 years +) capable of being permitted to participate in a study can provide consent. Parents/legal guardians of minors can also provide consent to allow their children to participate in a study.

Whenever possible, investigators should obtain the consent of participants. In practice, this means it is not sufficient to get potential participants to say “Yes.”

They also need to know what it is that they agree to. In other words, the psychologist should, so far as is practicable, explain what is involved in advance and obtain the informed consent of participants.

Informed consent must be informed, voluntary, and rational. Participants must be given relevant details to make an informed decision, including the purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits. Consent must be given voluntarily without undue coercion. And participants must have the capacity to rationally weigh the decision.

Components of informed consent include clearly explaining the risks and expected benefits, addressing potential therapeutic misconceptions about experimental treatments, allowing participants to ask questions, and describing methods to minimize risks like emotional distress.

Investigators should tailor the consent language and process appropriately for the study population. Obtaining meaningful informed consent is an ethical imperative for human subjects research.

The voluntary nature of participation should not be compromised through coercion or undue influence. Inducements should be fair and not excessive/inappropriate.

However, it is not always possible to gain informed consent. Where the researcher can’t ask the actual participants, a similar group of people can be asked how they would feel about participating.

If they think it would be OK, then it can be assumed that the real participants will also find it acceptable. This is known as presumptive consent.

However, a problem with this method is that there might be a mismatch between how people think they would feel/behave and how they actually feel and behave during a study.

In order for consent to be ‘informed,’ consent forms may need to be accompanied by an information sheet for participants’ setting out information about the proposed study (in lay terms), along with details about the investigators and how they can be contacted.

Special considerations exist when obtaining consent from vulnerable populations with decisional impairments, such as psychiatric patients, intellectually disabled persons, and children/adolescents. Capacity can vary widely so should be assessed individually, but interventions to improve comprehension may help. Legally authorized representatives usually must provide consent for children.

Participants must be given information relating to the following:

- A statement that participation is voluntary and that refusal to participate will not result in any consequences or any loss of benefits that the person is otherwise entitled to receive.

- Purpose of the research.

- All foreseeable risks and discomforts to the participant (if there are any). These include not only physical injury but also possible psychological.

- Procedures involved in the research.

- Benefits of the research to society and possibly to the individual human subject.

- Length of time the subject is expected to participate.

- Person to contact for answers to questions or in the event of injury or emergency.

- Subjects” right to confidentiality and the right to withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences.

Debriefing after a study involves informing participants about the purpose, providing an opportunity to ask questions, and addressing any harm from participation. Debriefing serves an educational function and allows researchers to correct misconceptions. It is an ethical imperative.

After the research is over, the participant should be able to discuss the procedure and the findings with the psychologist. They must be given a general idea of what the researcher was investigating and why, and their part in the research should be explained.

Participants must be told if they have been deceived and given reasons why. They must be asked if they have any questions, which should be answered honestly and as fully as possible.

Debriefing should occur as soon as possible and be as full as possible; experimenters should take reasonable steps to ensure that participants understand debriefing.

“The purpose of debriefing is to remove any misconceptions and anxieties that the participants have about the research and to leave them with a sense of dignity, knowledge, and a perception of time not wasted” (Harris, 1998).

The debriefing aims to provide information and help the participant leave the experimental situation in a similar frame of mind as when he/she entered it (Aronson, 1988).

Exceptions may exist if debriefing seriously compromises study validity or causes harm itself, like negative emotions in children. Consultation with an institutional review board guides exceptions.

Debriefing indicates investigators’ commitment to participant welfare. Harms may not be raised in the debriefing itself, so responsibility continues after data collection. Following up demonstrates respect and protects persons in human subjects research.

Protection of Participants

Researchers must ensure that those participating in research will not be caused distress. They must be protected from physical and mental harm. This means you must not embarrass, frighten, offend or harm participants.

Normally, the risk of harm must be no greater than in ordinary life, i.e., participants should not be exposed to risks greater than or additional to those encountered in their normal lifestyles.

The researcher must also ensure that if vulnerable groups are to be used (elderly, disabled, children, etc.), they must receive special care. For example, if studying children, ensure their participation is brief as they get tired easily and have a limited attention span.

Researchers are not always accurately able to predict the risks of taking part in a study, and in some cases, a therapeutic debriefing may be necessary if participants have become disturbed during the research (as happened to some participants in Zimbardo’s prisoners/guards study ).

Deception research involves purposely misleading participants or withholding information that could influence their participation decision. This method is controversial because it limits informed consent and autonomy, but can provide otherwise unobtainable valuable knowledge.

Types of deception include (i) deliberate misleading, e.g. using confederates, staged manipulations in field settings, deceptive instructions; (ii) deception by omission, e.g., failure to disclose full information about the study, or creating ambiguity.

The researcher should avoid deceiving participants about the nature of the research unless there is no alternative – and even then, this would need to be judged acceptable by an independent expert. However, some types of research cannot be carried out without at least some element of deception.

For example, in Milgram’s study of obedience , the participants thought they were giving electric shocks to a learner when they answered a question wrongly. In reality, no shocks were given, and the learners were confederates of Milgram.

This is sometimes necessary to avoid demand characteristics (i.e., the clues in an experiment that lead participants to think they know what the researcher is looking for).

Another common example is when a stooge or confederate of the experimenter is used (this was the case in both the experiments carried out by Asch ).

According to ethics codes, deception must have strong scientific justification, and non-deceptive alternatives should not be feasible. Deception that causes significant harm is prohibited. Investigators should carefully weigh whether deception is necessary and ethical for their research.

However, participants must be deceived as little as possible, and any deception must not cause distress. Researchers can determine whether participants are likely distressed when deception is disclosed by consulting culturally relevant groups.

Participants should immediately be informed of the deception without compromising the study’s integrity. Reactions to learning of deception can range from understanding to anger. Debriefing should explain the scientific rationale and social benefits to minimize negative reactions.

If the participant is likely to object or be distressed once they discover the true nature of the research at debriefing, then the study is unacceptable.

If you have gained participants’ informed consent by deception, then they will have agreed to take part without actually knowing what they were consenting to. The true nature of the research should be revealed at the earliest possible opportunity or at least during debriefing.

Some researchers argue that deception can never be justified and object to this practice as it (i) violates an individual’s right to choose to participate; (ii) is a questionable basis on which to build a discipline; and (iii) leads to distrust of psychology in the community.

Confidentiality

Protecting participant confidentiality is an ethical imperative that demonstrates respect, ensures honest participation, and prevents harms like embarrassment or legal issues. Methods like data encryption, coding systems, and secure storage should match the research methodology.

Participants and the data gained from them must be kept anonymous unless they give their full consent. No names must be used in a lab report .

Researchers must clearly describe to participants the limits of confidentiality and methods to protect privacy. With internet research, threats exist like third-party data access; security measures like encryption should be explained. For non-internet research, other protections should be noted too, like coding systems and restricted data access.

High-profile data breaches have eroded public trust. Methods that minimize identifiable information can further guard confidentiality. For example, researchers can consider whether birthdates are necessary or just ages.

Generally, reducing personal details collected and limiting accessibility safeguards participants. Following strong confidentiality protections demonstrates respect for persons in human subjects research.

What do we do if we discover something that should be disclosed (e.g., a criminal act)? Researchers have no legal obligation to disclose criminal acts and must determine the most important consideration: their duty to the participant vs. their duty to the wider community.

Ultimately, decisions to disclose information must be set in the context of the research aims.

Withdrawal from an Investigation

Participants should be able to leave a study anytime if they feel uncomfortable. They should also be allowed to withdraw their data. They should be told at the start of the study that they have the right to withdraw.

They should not have pressure placed upon them to continue if they do not want to (a guideline flouted in Milgram’s research).

Participants may feel they shouldn’t withdraw as this may ‘spoil’ the study. Many participants are paid or receive course credits; they may worry they won’t get this if they withdraw.

Even at the end of the study, the participant has a final opportunity to withdraw the data they have provided for the research.

Ethical Issues in Psychology & Socially Sensitive Research

There has been an assumption over the years by many psychologists that provided they follow the BPS or APA guidelines when using human participants and that all leave in a similar state of mind to how they turned up, not having been deceived or humiliated, given a debrief, and not having had their confidentiality breached, that there are no ethical concerns with their research.

But consider the following examples:

a) Caughy et al. 1994 found that middle-class children in daycare at an early age generally score less on cognitive tests than children from similar families reared in the home.

Assuming all guidelines were followed, neither the parents nor the children participating would have been unduly affected by this research. Nobody would have been deceived, consent would have been obtained, and no harm would have been caused.

However, consider the wider implications of this study when the results are published, particularly for parents of middle-class infants who are considering placing their young children in daycare or those who recently have!

b) IQ tests administered to black Americans show that they typically score 15 points below the average white score.

When black Americans are given these tests, they presumably complete them willingly and are not harmed as individuals. However, when published, findings of this sort seek to reinforce racial stereotypes and are used to discriminate against the black population in the job market, etc.

Sieber & Stanley (1988) (the main names for Socially Sensitive Research (SSR) outline 4 groups that may be affected by psychological research: It is the first group of people that we are most concerned with!

- Members of the social group being studied, such as racial or ethnic group. For example, early research on IQ was used to discriminate against US Blacks.

- Friends and relatives of those participating in the study, particularly in case studies, where individuals may become famous or infamous. Cases that spring to mind would include Genie’s mother.

- The research team. There are examples of researchers being intimidated because of the line of research they are in.

- The institution in which the research is conducted.

salso suggest there are 4 main ethical concerns when conducting SSR:

- The research question or hypothesis.

- The treatment of individual participants.

- The institutional context.

- How the findings of the research are interpreted and applied.

Ethical Guidelines For Carrying Out SSR

Sieber and Stanley suggest the following ethical guidelines for carrying out SSR. There is some overlap between these and research on human participants in general.

Privacy : This refers to people rather than data. Asking people questions of a personal nature (e.g., about sexuality) could offend.

Confidentiality: This refers to data. Information (e.g., about H.I.V. status) leaked to others may affect the participant’s life.

Sound & valid methodology : This is even more vital when the research topic is socially sensitive. Academics can detect flaws in methods, but the lay public and the media often don’t.

When research findings are publicized, people are likely to consider them fact, and policies may be based on them. Examples are Bowlby’s maternal deprivation studies and intelligence testing.

Deception : Causing the wider public to believe something, which isn’t true by the findings, you report (e.g., that parents are responsible for how their children turn out).

Informed consent : Participants should be made aware of how participating in the research may affect them.

Justice & equitable treatment : Examples of unjust treatment are (i) publicizing an idea, which creates a prejudice against a group, & (ii) withholding a treatment, which you believe is beneficial, from some participants so that you can use them as controls.

Scientific freedom : Science should not be censored, but there should be some monitoring of sensitive research. The researcher should weigh their responsibilities against their rights to do the research.

Ownership of data : When research findings could be used to make social policies, which affect people’s lives, should they be publicly accessible? Sometimes, a party commissions research with their interests in mind (e.g., an industry, an advertising agency, a political party, or the military).

Some people argue that scientists should be compelled to disclose their results so that other scientists can re-analyze them. If this had happened in Burt’s day, there might not have been such widespread belief in the genetic transmission of intelligence. George Miller (Miller’s Magic 7) famously argued that we should give psychology away.

The values of social scientists : Psychologists can be divided into two main groups: those who advocate a humanistic approach (individuals are important and worthy of study, quality of life is important, intuition is useful) and those advocating a scientific approach (rigorous methodology, objective data).

The researcher’s values may conflict with those of the participant/institution. For example, if someone with a scientific approach was evaluating a counseling technique based on a humanistic approach, they would judge it on criteria that those giving & receiving the therapy may not consider important.

Cost/benefit analysis : It is unethical if the costs outweigh the potential/actual benefits. However, it isn’t easy to assess costs & benefits accurately & the participants themselves rarely benefit from research.

Sieber & Stanley advise that researchers should not avoid researching socially sensitive issues. Scientists have a responsibility to society to find useful knowledge.

- They need to take more care over consent, debriefing, etc. when the issue is sensitive.

- They should be aware of how their findings may be interpreted & used by others.

- They should make explicit the assumptions underlying their research so that the public can consider whether they agree with these.

- They should make the limitations of their research explicit (e.g., ‘the study was only carried out on white middle-class American male students,’ ‘the study is based on questionnaire data, which may be inaccurate,’ etc.

- They should be careful how they communicate with the media and policymakers.

- They should be aware of the balance between their obligations to participants and those to society (e.g. if the participant tells them something which they feel they should tell the police/social services).

- They should be aware of their own values and biases and those of the participants.

Arguments for SSR

- Psychologists have devised methods to resolve the issues raised.

- SSR is the most scrutinized research in psychology. Ethical committees reject more SSR than any other form of research.

- By gaining a better understanding of issues such as gender, race, and sexuality, we are able to gain greater acceptance and reduce prejudice.

- SSR has been of benefit to society, for example, EWT. This has made us aware that EWT can be flawed and should not be used without corroboration. It has also made us aware that the EWT of children is every bit as reliable as that of adults.

- Most research is still on white middle-class Americans (about 90% of research is quoted in texts!). SSR is helping to redress the balance and make us more aware of other cultures and outlooks.

Arguments against SSR

- Flawed research has been used to dictate social policy and put certain groups at a disadvantage.

- Research has been used to discriminate against groups in society, such as the sterilization of people in the USA between 1910 and 1920 because they were of low intelligence, criminal, or suffered from psychological illness.

- The guidelines used by psychologists to control SSR lack power and, as a result, are unable to prevent indefensible research from being carried out.

American Psychological Association. (2002). American Psychological Association ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. www.apa.org/ethics/code2002.html

Baumrind, D. (1964). Some thoughts on ethics of research: After reading Milgram’s” Behavioral study of obedience.”. American Psychologist , 19 (6), 421.

Caughy, M. O. B., DiPietro, J. A., & Strobino, D. M. (1994). Day‐care participation as a protective factor in the cognitive development of low‐income children. Child development , 65 (2), 457-471.

Harris, B. (1988). Key words: A history of debriefing in social psychology. In J. Morawski (Ed.), The rise of experimentation in American psychology (pp. 188-212). New York: Oxford University Press.

Rosenthal, R., & Rosnow, R. L. (1984). Applying Hamlet’s question to the ethical conduct of research: A conceptual addendum. American Psychologist, 39(5) , 561.

Sieber, J. E., & Stanley, B. (1988). Ethical and professional dimensions of socially sensitive research. American psychologist , 43 (1), 49.

The British Psychological Society. (2010). Code of Human Research Ethics. www.bps.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/code_of_human_research_ethics.pdf

Further Information

- MIT Psychology Ethics Lecture Slides

BPS Documents

- Code of Ethics and Conduct (2018)

- Good Practice Guidelines for the Conduct of Psychological Research within the NHS

- Guidelines for Psychologists Working with Animals

- Guidelines for ethical practice in psychological research online

APA Documents

APA Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct

Ethics & Psychology

- General Resources

- Animal Subjects

- Human Subjects

- Case Studies

Collections of Cases

- Ethics Case Studies in Mental Health Research A large collection of cases addressing issues such as human participants in research, conflict of interest, and the responsible collection, management, and use of research data.

- Ethics Education Library -Psychology Case Studies A collection of over 90 case studies from the Ethics Education Library.

- Ethics Rounds A collection of case studies published in the American Psychological Association's "Monitor on Ethics".

Case Investigations by Government Agencies/Professional Organizations

- Office of Research Integrity Cases summaries from the past four years of investigations and inquiries done by the Office of Research Integrity. Also includes short case summaries from 1994 onwards.

Books, Anthologies, & More

- << Previous: Human Subjects

- Last Updated: Dec 15, 2023 10:40 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.iit.edu/psychologyethics

- High School

- You don't have any recent items yet.

- You don't have any courses yet.

- You don't have any books yet.

- You don't have any Studylists yet.

- Information

PSY-510 Case Study 2

Contemporary and ethical issues in psychology (psy-510), grand canyon university, students also viewed.

- Benchmark Critical Thinking

- Case Study Handling Disparate 3

- Case Study Handling Disparate 2

- Case Study Handling Disparate 1

- Academic honesty and plagiarism psy 510

- ethical consultation

Related documents

- Dr. Vaji Study

- Violated if they are not psy 510

- Testimony 101

- 1Obj 3.1 and 3.3 Benchmark – Critical Thinking

- Week Three Critical Thinking Essay (Final)

- Duty To Protect - worksheet

Preview text

Psy-510 contemporary and ethical issues in psychology, case study: duty to protect.

Directions: In a minimum of 50 words, for each question, thoroughly answer each of the questions below regarding the case featuring Dr. Daniela Yeung. Use one to two scholarly resources to support your answers. Use in-text citations, when appropriate, according to APA formatting. 1. Why is this an ethical dilemma? Which APA Ethical Principles help frame the nature of the dilemma? Dr. Daniela Yeung's case presents an ethical dilemma because it involves a conflict between two or more ethical principles that guide professional conduct in psychology. In Dr. Yeung's case, the ethical dilemma could be framed by the following APA Ethical Principles: Beneficence and Nonmaleficence: This principle requires psychologists to strive to benefit those with whom they work and take care to do no harm. In Dr. Yeung's case, she might be torn between doing what is beneficial for her client and avoiding harm to others who might be affected by her client's actions (APA, 2017). Fidelity and Responsibility: Psychologists are expected to establish relationships of trust with those with whom they work. They are also responsible for their professional behavior, including avoiding conflicts of interest. Dr. Yeung might be facing a dilemma between maintaining trust with her client and fulfilling her responsibility to society (APA, 2017). Respect for People's Rights and Dignity: Psychologists respect the dignity and worth of all people, and the rights of individuals to privacy, confidentiality, and self-determination. Dr. Yeung's dilemma might involve respecting her client's right to confidentiality while considering the potential harm to others (APA, 2017). 2. Who are the stakeholders and how will they be affected by how Dr. Yeung resolves this dilemma? The stakeholders in Dr. Yeung's dilemma are: 1. Dr. Yeung: As the primary decision-maker, the way she resolves the dilemma will directly impact her professional and ethical standing. 2. The Patient: The patient's health and trust in medical professionals are at stake. The resolution could affect their health outcomes and their perception of medical ethics. 3. The Medical Community: This includes other doctors, medical staff, and the broader healthcare system. The resolution of the dilemma could set a precedent that influences future ethical decisions.

- The Pharmaceutical Company: If the company is promoting a drug with potentially harmful side effects, their reputation and financial standing could be affected by Dr. Yeung's decision. If she chooses to prescribe the drug, she may face ethical dilemmas and potential legal issues. If he refuses, she may face pressure from the pharmaceutical company or even her peers. If the drug is prescribed and causes harm, the patient's health could be negatively impacted. If the drug is not prescribed, the patient may miss out on potentially beneficial treatment. The decision could set a precedent for how similar ethical dilemmas will be handled in the future. It could also impact the trust between patients and healthcare providers. If Dr. Yeung refuses to prescribe the drug, it could lead to a loss in sales. If she exposes potentially harmful side effects, the company could face legal action and damage to their reputation.

- Does this situation meet the standards set by the Tarasoff Duty to Protect statute (see Chapter 8)? Dr. Yeung has an important decision to make, as a psychologist who knows the importance of protecting confidentiality and as a researcher who knows the responsibility to protect both herself and the research participants. How might Dr. Yeung’s decision be influenced by whether or not her state (e. Arizona) includes researchers within the Duty to Protect statute’s influence? The Tarasoff Duty to Protect statute is a legal principle that originated from the case of Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California. It imposes a duty on mental health professionals to protect individuals who are being threatened with bodily harm by a patient (Knoll, 2019). The professional is responsible for fulfilling their duty by exerting a reasonable effort to inform the intended victim and notify law enforcement officials. The determination of whether this duty aligns with the standards established by the Tarasoff Duty to Protect statute cannot be definitively ascertained without specific details regarding the situation. Nevertheless, if Dr. Yeung's patient has explicitly expressed a clear and immediate intention to cause harm to another individual, then the Tarasoff Duty may be applicable. The application of the Tarasoff Duty varies across different states, with some states explicitly encompassing researchers within the Duty to Protect statute, while others do not. In the event that Dr. Yeung practices in a state such as Arizona, which does not explicitly include researchers, she may not possess a legal obligation to breach confidentiality. However, ethical considerations may still impel her to take action. Even in the absence of a legal requirement, Dr. Yeung may still feel ethically compelled to safeguard potential victims. The Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct established by the American Psychological Association stipulates that psychologists should undertake reasonable measures to protect the well-being and rights of those with whom they engage. Dr. Yeung's decision-making process may be influenced by various factors: if the threat is severe and immediate, she may experience a heightened compulsion to breach confidentiality; if the threat is ambiguous or uncertain, she may opt to continue monitoring the situation. It is important to acknowledge that breaching

Standard 4: Discussing the Limits of Confidentiality This standard requires psychologists to discuss the limits of confidentiality with their clients. If Dr. Yeung has not had this discussion with her clients, she would be violating this standard. Standard 4: Disclosures This standard states that psychologists may disclose confidential information with the appropriate consent of the individual or organizational client, or the individual's legally authorized representative. If Dr. Yeung is disclosing information without proper consent, she would be in violation of this standard. Standard 8: Institutional Approval This standard requires psychologists to seek approval from an appropriate institution before conducting research. If Dr. Yeung is conducting research without proper approval, she would be violating this standard. Without more specific details about Dr. Yeung's case, it's difficult to identify other potentially relevant standards. However, some other standards that might apply include: Standard 2: Maintaining Competence - If Dr. Yeung is not making ongoing efforts to maintain her competence in her field, she could be in violation of this standard. Standard 3: Multiple Relationships - If Dr. Yeung is involved in multiple relationships that could impair her objectivity, competence, or effectiveness, she could be in violation of this standard. Standard 9: Bases for Assessments - If Dr. Yeung is making assessments based on information and techniques sufficient to substantiate her findings, she could be in violation of this standard. 6. What are Dr. Yeung’s ethical alternatives for resolving this dilemma? Which alternative best reflects the Ethics Code aspirational principles and enforceable standards, legal standards, and obligations to stakeholders? Can you identify the ethical theory (discussed in Chapter 4) guiding your decision? Dr. Daniela Yeung, facing an ethical dilemma, has several alternatives:

- Continue the therapy sessions without disclosing her relationship with the client's ex- spouse.

- Disclose her relationship with the client's ex-spouse and continue the therapy sessions if the client is comfortable.

- Refer the client to another therapist due to potential conflict of interest. The best alternative that reflects the Ethics Code aspirational principles, legal standards, and obligations to stakeholders would be to disclose her relationship with the client's ex- spouse and, based on the client's comfort level, decide whether to continue the therapy or refer the client to another therapist. This approach respects the principles of autonomy,

beneficence, non-maleficence, justice, and fidelity. It also aligns with legal standards of informed consent and professional boundaries. The ethical theory guiding this decision is Deontology. This theory emphasizes duties and rules, and the act of telling the truth is seen as a moral duty (Fisher, 2021). It also values the principle of autonomy, respecting the client's right to make informed decisions about their therapy (Fisher, 2021). 7. What steps should Dr. Yeung take to implement her decision and monitor its effect? Develop a Detailed Plan Identify the tasks that need to be accomplished for the decision to be implemented. Determine the resources required (e., personnel, budget, time). Establish a timeline for implementation. Communicate the Decision Clearly communicate the decision to all relevant stakeholders. Explain the rationale behind the decision and how it will benefit the organization. Delegate Tasks Assign tasks to team members based on their skills and capabilities. Ensure everyone understands their responsibilities and deadlines. Provide Support and Resources Ensure team members have the resources and support they need to carry out their tasks. Be available to answer questions and provide guidance. Monitor Progress Regularly check on the progress of the implementation. Use metrics to measure the effectiveness of the decision. Evaluate and Adjust After the decision has been implemented, evaluate its effectiveness. If necessary, make adjustments based on feedback and results. References: American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct (2002, amended effective June 1, 2010, and January 1, 2017). apa/ethics/code/index.html Fisher, C. B. (2021). Decoding the ethics code (5th ed., pp. 59). SAGE Publications.

- Multiple Choice

Course : Contemporary and Ethical Issues in Psychology (PSY-510)

University : grand canyon university, this is a preview.

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Get 30 days of free Premium

Share your documents to unlock

Why is this page out of focus?

Yogi, P. \(2015, February 11\). Ethical issues in psychology. Psych Yogi. Retrieved from http://psychyogi.org/ethical-issues-in-psychology.

CITE AS: Yogi, P. \(2015, February 11\). Ethical issues in psychology. Psych Yogi. http://psychyogi.org/ethical-issues-in-psychology.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

In this case, the patient did not tell his therapist of intent to harm himself and a former girlfriend's new boyfriend but did communicate this to his father. The father in turn told the therapist of his conversation and the therapist encouraged the father to have his son hospitalized.

Human experimentation is a very interesting topic in the world of human psychology. While some famous experiments in psychology have left test subjects temporarily distressed, others have left their participants with life-long psychological issues. In either case, it's easy to ask the question: "What's ethical when it comes to science?"

The annals of psychology are unfortunately replete with examples of ethical violations that serve as stark reminders of the importance of maintaining rigorous ethical standards. These case studies not only illustrate the potential for harm but also provide valuable lessons for future practitioners and researchers.

Section II Ethical Issues in Working with Diverse Populations; Section III Legal, Research, and Organizational Issues; 21 Major Legal Cases That Have Influenced Mental Health Ethics; 22 Ethical Considerations in Forensic Evaluations in Family Court; 23 Ethical Issues in Online Research; 24 Ethical Issues in International Research

Ethical Issues in Psychology & Socially Sensitive Research. ... Friends and relatives of those participating in the study, particularly in case studies, where individuals may become famous or infamous. Cases that spring to mind would include Genie's mother. The research team. There are examples of researchers being intimidated because of the ...

Ethics & Psychology; Case Studies; Search this Guide Search. Ethics & Psychology. Ethical Issues in clinical practice and research. General Resources; ... Ethics Case Studies in Mental Health Research. A large collection of cases addressing issues such as human participants in research, conflict of interest, and the responsible collection ...

1 Continuing Psychology Education Inc. P.O. Box 12202 Albany, NY 12212 FAX: (858) 272-5809 Phone: 1 800 281-5068 Email: [email protected] www.texcpe.com ETHICS: CASE STUDIES I Presented by CONTINUING PSYCHOLOGY EDUCATION INC. 6 CONTINUING EDUCATION CONTACT HOURS "What makes an action right is the principle that guides it."

PSY-510 Contemporary and Ethical Issues in Psychology Case Study: Duty to Protect. Directions: In a minimum of 50 words, for each question, thoroughly answer each of the questions below regarding the case featuring Dr. Daniela Yeung. Use one to two scholarly resources to support your answers. Use in-text citations, when appropriate, according ...

As the study of the mind and behaviour, psychology requires certain ethical guidelines when dealing with people as subjects. When we talk about 'ethical issues' in psychology, we are referring to ideas and topics that invoke our moral responsibility. Ethical practices in psychology have changed over time. In 1947, at the end of the Second

Learn about APA's ethics code, multiple relationships, confidentiality, billing and informed consent about record keeping. ... Potential ethical violations. ... Adapted from "10 ways practitioners can avoid frequent ethical pitfalls" APA Monitor on Psychology. Date created: 2010. Ethics at APA. Ethics Code. Filing an Ethics Complaint.