Action Research: Steps, Benefits, and Tips

Introduction

History of action research, what is the definition of action research, types of action research, conducting action research.

Action research is an approach to qualitative inquiry in social science research that involves the search for practical solutions to everyday issues. Rooted in real-world problems, it seeks not just to understand but also to act, bringing about positive change in specific contexts. Often distinguished by its collaborative nature, the action research process goes beyond traditional research paradigms by emphasizing the involvement of those being studied in resolving social conflicts and effecting positive change.

The value of action research lies not just in its outcomes, but also in the process itself, where stakeholders become active participants rather than mere subjects. In this article, we'll examine action research in depth, shedding light on its history, principles, and types of action research.

Tracing its roots back to the mid-20th century, Kurt Lewin developed classical action research as a response to traditional research methods in the social sciences that often sidelined the very communities they studied. Proponents of action research championed the idea that research should not just be an observational exercise but an actionable one that involves devising practical solutions. Advocates believed in the idea of research leading to immediate social action, emphasizing the importance of involving the community in the process.

Applications for action research

Over the years, action research has evolved and diversified. From its early applications in social psychology and organizational development, it has branched out into various fields such as education, healthcare, and community development, informing questions around improving schools, minority problems, and more. This growth wasn't just in application, but also in its methodologies.

How is action research different?

Like all research methodologies, effective action research generates knowledge. However, action research stands apart in its commitment to instigate tangible change. Traditional research often places emphasis on passive observation , employing data collection methods primarily to contribute to broader theoretical frameworks . In contrast, action research is inherently proactive, intertwining the acts of observing and acting.

The primary goal isn't just to understand a problem but to solve or alleviate it. Action researchers partner closely with communities, ensuring that the research process directly benefits those involved. This collaboration often leads to immediate interventions, tweaks, or solutions applied in real-time, marking a departure from other forms of research that might wait until the end of a study to make recommendations.

This proactive, change-driven nature makes action research particularly impactful in settings where immediate change is not just beneficial but essential.

Action research is best understood as a systematic approach to cooperative inquiry. Unlike traditional research methodologies that might primarily focus on generating knowledge, action research emphasizes producing actionable solutions for pressing real-world challenges.

This form of research undertakes a cyclic and reflective journey, typically cycling through stages of planning , acting, observing, and reflecting. A defining characteristic of action research is the collaborative spirit it embodies, often dissolving the rigid distinction between the researcher and the researched, leading to mutual learning and shared outcomes.

Advantages of action research

One of the foremost benefits of action research is the immediacy of its application. Since the research is embedded within real-world issues, any findings or solutions derived can often be integrated straightaway, catalyzing prompt improvements within the concerned community or organization. This immediacy is coupled with the empowering nature of the methodology. Participants aren't mere subjects; they actively shape the research process, giving them a tangible sense of ownership over both the research journey and its eventual outcomes.

Moreover, the inherent adaptability of action research allows researchers to tweak their approaches responsively based on live feedback. This ensures the research remains rooted in the evolving context, capturing the nuances of the situation and making any necessary adjustments. Lastly, this form of research tends to offer a comprehensive understanding of the issue at hand, harmonizing socially constructed theoretical knowledge with hands-on insights, leading to a richer, more textured understanding.

Disadvantages of action research

Like any methodology, action research isn't devoid of challenges. Its iterative nature, while beneficial, can extend timelines. Researchers might find themselves engaged in multiple cycles of observation, reflection, and action before arriving at a satisfactory conclusion. The intimate involvement of the researcher with the research participants , although key to collaboration, opens doors to potential conflicts. Through collaborative problem solving, disagreements can lead to richer and more nuanced solutions, but it can take considerable time and effort.

Another limitation stems from its focus on a specific context: results derived from a particular action research project might not always resonate or be applicable in a different context or with a different group. Lastly, the depth of collaboration this methodology demands means all stakeholders need to be deeply invested, and such a level of commitment might not always be feasible.

Examples of action research

To illustrate, let's consider a few scenarios. Imagine a classroom where a teacher observes dwindling student participation. Instead of sticking to conventional methods, the teacher experiments with introducing group-based activities. As the outcomes unfold, the teacher continually refines the approach based on student feedback, eventually leading to a teaching strategy that rejuvenates student engagement.

In a healthcare context, hospital staff who recognize growing patient anxiety related to certain procedures might innovate by introducing a new patient-informing protocol. As they study the effects of this change, they could, through iterations, sculpt a procedure that diminishes patient anxiety.

Similarly, in the realm of community development, a community grappling with the absence of child-friendly public spaces might collaborate with local authorities to conceptualize a park. As they monitor its utilization and societal impact, continual feedback could refine the park's infrastructure and design.

Contemporary action research, while grounded in the core principles of collaboration, reflection, and change, has seen various adaptations tailored to the specific needs of different contexts and fields. These adaptations have led to the emergence of distinct types of action research, each with its unique emphasis and approach.

Collaborative action research

Collaborative action research emphasizes the joint efforts of professionals, often from the same field, working together to address common concerns or challenges. In this approach, there's a strong emphasis on shared responsibility, mutual respect, and co-learning. For example, a group of classroom teachers might collaboratively investigate methods to improve student literacy, pooling their expertise and resources to devise, implement, and refine strategies for improving teaching.

Participatory action research

Participatory action research (PAR) goes a step further in dissolving the barriers between the researcher and the researched. It actively involves community members or stakeholders not just as participants, but as equal partners in the entire research process. PAR is deeply democratic and seeks to empower participants, fostering a sense of agency and ownership. For instance, a participatory research project might involve local residents in studying and addressing community health concerns, ensuring that the research process and outcomes are both informed by and beneficial to the community itself.

Educational action research

Educational action research is tailored specifically to practical educational contexts. Here, educators take on the dual role of teacher and researcher, seeking to improve teaching practices, curricula, classroom dynamics, or educational evaluation. This type of research is cyclical, with educators implementing changes, observing outcomes, and reflecting on results to continually enhance the educational experience. An example might be a teacher studying the impact of technology integration in her classroom, adjusting strategies based on student feedback and learning outcomes.

Community-based action research

Another noteworthy type is community-based action research, which focuses primarily on community development and well-being. Rooted in the principles of social justice, this approach emphasizes the collective power of community members to identify, study, and address their challenges. It's particularly powerful in grassroots movements and local development projects where community insights and collaboration drive meaningful, sustainable change.

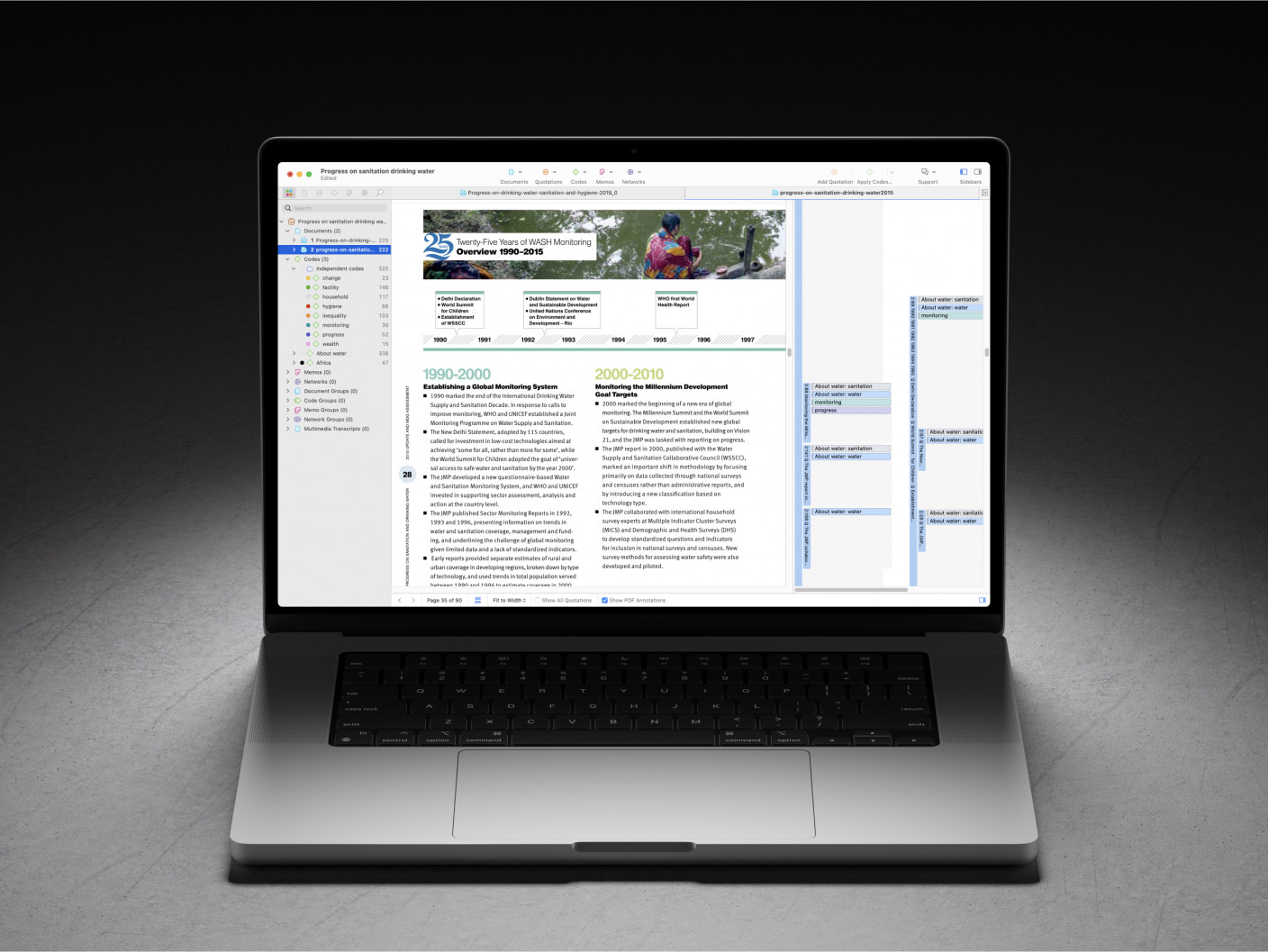

Key insights and critical reflection through research with ATLAS.ti

Organize all your data analysis and insights with our powerful interface. Download a free trial today.

Engaging in action research is rooted in practicality yet deeply connected to theory. Action researchers should take the essentials of an action research study and the significance of a typical research cycle into consideration.

Understanding the action research cycle

At the heart of action research is its cycle, a structured yet adaptable framework guiding the research. This cycle embodies the iterative nature of action research, emphasizing that learning and change evolve through repetition and reflection.

The typical stages include:

- Identifying a problem : This is the starting point where the action researcher pinpoints a pressing issue or challenge that demands attention.

- Planning : Here, the researcher devises an action research strategy aimed at addressing the identified problem. In action research, network resources, participant consultation, and the literature review are core components in planning.

- Action : The planned strategies are then implemented in this stage. This 'action' phase is where theoretical knowledge meets practical application.

- Observation : Post-implementation, the researcher observes the outcomes and effects of the action. This stage ensures that the research remains grounded in the real-world context.

- Critical reflection : This part of the cycle involves analyzing the observed results to draw conclusions about their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement.

- Revision : Based on the insights from reflection, the initial plan is revised, marking the beginning of another cycle.

Rigorous research and iteration

It's essential to understand that while action research is deeply practical, it doesn't sacrifice rigor . The cyclical process ensures that the research remains thorough and robust. Each iteration of the cycle in an action research project refines the approach, drawing it closer to an effective solution.

The role of the action researcher

The action researcher stands at the nexus of theory and practice. Not just an observer, the researcher actively engages with the study's participants, collaboratively navigating through the research cycle by conducting interviews, participant observations, and member checking . This close involvement ensures that the study remains relevant, timely, and responsive.

Drawing conclusions and informing theory

As the research progresses through multiple iterations of data collection and data analysis , drawing conclusions becomes an integral aspect. These conclusions, while immediately beneficial in addressing the practical issue at hand, also serve a broader purpose. They inform theory, enriching the academic discourse and providing valuable insights for future research.

Identifying actionable insights

Keep in mind that action research should facilitate implications for professional practice as well as space for systematic inquiry. As you draw conclusions about the knowledge generated from action research, consider how this knowledge can create new forms of solutions to the pressing concern you set out to address.

Collecting data and analyzing data starts with ATLAS.ti

Download a free trial of our intuitive software to make the most of your research.

The Action Research cycle

Cycles provide a useful way of thinking about and describing an Action Research process. Each cycle is made up of four phases - Observe, Reflect, Plan and Act.

Experience in Reconnect and NAYSS has shown that the observe phase is often the logical starting point for Action Research – you notice an issue that you want to explore and begin by recording your observations.

The next phase is to take the time to reflect on the observations and extract meaning from them.

Based on your observations and reflections, this is the time to prepare a plan of action – what needs to be done and who needs to do it.

This is the part of the cycle where you implement your plans.

Each stage of the Action Research cycle is discussed in more detail below.

Some stages of observation are:

- To look at what is happening

- Describe what has happened

- Record what has happened

Good observation requires looking at what is happening and describing it accurately. Its purpose is to provide a sound base for reflection by producing a widely accepted understanding of what actually happened (Quixley, 1997 in Reconnect Action Research Kit, 2000).

Formal and informal data collection strategies

There are a range of ways to collect data. For example, data collection from clients could include verbal communication, such as face-to-face or by telephone. Data collection from other services could be obtained in writing and structured to answer specific questions.

The observe stage can be a good place to start an Action Research cycle by:

- considering something that is happening or not happening

- using available information

- finding out new information

- involving a range of people to describe what they think is occurring.

Observation tools

- Questionnaires/surveys

- Minutes from forums or meetings

- Informal interviews and discussions and keeping a journal in the agency to track insights, observations, anecdotes and questions raised

- Group brainstorming

- Client information, referral sheets, work logbooks and other agency paperwork

- Email and websites where people can leave comments and ask questions

- Wall charts/ graffiti boards

- Information systems such as computer files, coloured folders for different questions and suggestion boxes.

Focus questions

What did you notice?

What were the outcomes of your actions?

What happened?

Did different stakeholders observe different things?

What is going on for your clients?

Is there anything new or different?

Can you enrich your understanding of the situation by talking with your clients and/or different stakeholders about what you have observed and to gain different perspectives?

Stages of reflection include:

- involve stakeholders to gain different interpretations.

- talking it over

- sharing insights

- piecing things together or ‘jigsawing’.

- Sharing ideas with others so that a range of interpretations and ‘meanings’ can be considered. Float ideas by:

- making informed guesses based on the information gathered

- comparing what you have observed with competing evidence

- looking at alternative explanations.

This is the stage in the cycle where you need to spend time thinking about the findings of the observations, negotiating meaning with stakeholders and building a shared understanding.

Suggestions for reflecting

- Have a look at what has been done, the information gathered about it and let it sit for a while.

- Talk to people to get a range of perspectives.

- Have some quiet time to work out what you think and encourage others to do the same.

- Share ideas and be honest about them.

- Be open about what is going on.

- Respect different understandings and interpretations.

- Be aware that people’s values and experiences will influence their reflections.

- Think about issues in their particular context.

- Give ideas/theories the opportunity to develop over time.

What does it mean?

What do the results of your actions tell you?

What further action is suggested?

What new knowledge did you generate?

Have you challenged your assumptions and those of your stakeholders?

Who agrees? Who disagrees? And what does this reveal?

Have you reflected on how your observations impact on the young people involved? Their families? The community?

Planning includes:

- Clarifying the questions being asked

- Identifying the actions to be tried out

- Developing an action plan.

All stages should be participatory and collaborative and the planning stage is no different. At this point, stakeholders should come together to talk about what they will do and how they will do it. It is important at this point to directly involve those affected by the research question. Each member of the group undertaking the Action Research itself should make active contributions to the plan and work collaboratively with one another.

You will find that a well thought out, flexible and coordinated action plan will prove effective, particularly in serving a wide range of stakeholders. For example, if workers across five community organisations are involved in trialling a new approach under a particular Action Research project, it is critical that they have a clear, agreed action plan that all are committed to implementing.

Planning process

- Using the reflection and thinking from the previous stage involving stakeholders and different ideas and perspectives.

- Asking - what do we want to do?

- Work out a priority of what you want to do.

- Look at your resources, i.e. what you need to achieve your goals.

- After looking at your resources you may need to re-think priorities.

- Collaboratively develop strategies for putting ideas into action – who is doing what and how?

- Think through the implications of the intended action .

- Timetable your action plan – when will things be done by?

- Build in observation and reflection methods - how will we keep an eye on what is happening?

- Planning doesn’t need to be difficult.

- Planning often means clarifying and refining a plan as new and changed understandings emerge.

- Collaborative planning with stakeholders is important to getting the research question right.

- Using or adapting existing ways of involving clients in services may assist in planning.

What are you planning on doing?

Who is doing what?

Who is affected?

Who do you need to involve?

What made you think about making this change or examining this particular aspect of the problem?

What improvement do you hope to see?

What knowledge do you hope to generate?

Action includes:

- Do what you said you were going to do – systematically and creatively implement plans

- Communicate with others and involve them in the process

- Keep track of what happens.

- Make sure you have agreement on the who, what, when and how of the action plan.

- Actions reflect the plan although the plan can be changed or abandoned.

- Actions are not separate from research - the aim is to test questions in practice.

- Documenting action as it happens makes describing what happened much easier – record who did what, when and how.

- Action does not have a particular end point. If it isn’t working, it can be reviewed and re-planned any time.

- It does not have to be complex, technical or flashy. It may involve a small change at first like testing ideas and coming up with an initial strategy. You may have to try a number of things before you feel you are on to something, and you will learn something from everything that happens.

What are you doing?

What are your actions?

What is happening?

How are you recording this?

This page is part of: Reconnect Action Research Induction Kit

- Share Share this page: https://www.dss.gov.au/reconnect-action-research-induction-kit/action-research-cycle Copy shareable link Close

IMAGES

VIDEO