6.1 Overview of Non-Experimental Research

Learning objectives.

- Define non-experimental research, distinguish it clearly from experimental research, and give several examples.

- Explain when a researcher might choose to conduct non-experimental research as opposed to experimental research.

What Is Non-Experimental Research?

Non-experimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable. Rather than manipulating an independent variable, researchers conducting non-experimental research simply measure variables as they naturally occur (in the lab or real world).

Most researchers in psychology consider the distinction between experimental and non-experimental research to be an extremely important one. This is because although experimental research can provide strong evidence that changes in an independent variable cause differences in a dependent variable, non-experimental research generally cannot. As we will see, however, this inability to make causal conclusions does not mean that non-experimental research is less important than experimental research.

When to Use Non-Experimental Research

As we saw in the last chapter , experimental research is appropriate when the researcher has a specific research question or hypothesis about a causal relationship between two variables—and it is possible, feasible, and ethical to manipulate the independent variable. It stands to reason, therefore, that non-experimental research is appropriate—even necessary—when these conditions are not met. There are many times in which non-experimental research is preferred, including when:

- the research question or hypothesis relates to a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables (e.g., How accurate are people’s first impressions?).

- the research question pertains to a non-causal statistical relationship between variables (e.g., is there a correlation between verbal intelligence and mathematical intelligence?).

- the research question is about a causal relationship, but the independent variable cannot be manipulated or participants cannot be randomly assigned to conditions or orders of conditions for practical or ethical reasons (e.g., does damage to a person’s hippocampus impair the formation of long-term memory traces?).

- the research question is broad and exploratory, or is about what it is like to have a particular experience (e.g., what is it like to be a working mother diagnosed with depression?).

Again, the choice between the experimental and non-experimental approaches is generally dictated by the nature of the research question. Recall the three goals of science are to describe, to predict, and to explain. If the goal is to explain and the research question pertains to causal relationships, then the experimental approach is typically preferred. If the goal is to describe or to predict, a non-experimental approach will suffice. But the two approaches can also be used to address the same research question in complementary ways. For example, Similarly, after his original study, Milgram conducted experiments to explore the factors that affect obedience. He manipulated several independent variables, such as the distance between the experimenter and the participant, the participant and the confederate, and the location of the study (Milgram, 1974) [1] .

Types of Non-Experimental Research

Non-experimental research falls into three broad categories: cross-sectional research, correlational research, and observational research.

First, cross-sectional research involves comparing two or more pre-existing groups of people. What makes this approach non-experimental is that there is no manipulation of an independent variable and no random assignment of participants to groups. Imagine, for example, that a researcher administers the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale to 50 American college students and 50 Japanese college students. Although this “feels” like a between-subjects experiment, it is a cross-sectional study because the researcher did not manipulate the students’ nationalities. As another example, if we wanted to compare the memory test performance of a group of cannabis users with a group of non-users, this would be considered a cross-sectional study because for ethical and practical reasons we would not be able to randomly assign participants to the cannabis user and non-user groups. Rather we would need to compare these pre-existing groups which could introduce a selection bias (the groups may differ in other ways that affect their responses on the dependent variable). For instance, cannabis users are more likely to use more alcohol and other drugs and these differences may account for differences in the dependent variable across groups, rather than cannabis use per se.

Cross-sectional designs are commonly used by developmental psychologists who study aging and by researchers interested in sex differences. Using this design, developmental psychologists compare groups of people of different ages (e.g., young adults spanning from 18-25 years of age versus older adults spanning 60-75 years of age) on various dependent variables (e.g., memory, depression, life satisfaction). Of course, the primary limitation of using this design to study the effects of aging is that differences between the groups other than age may account for differences in the dependent variable. For instance, differences between the groups may reflect the generation that people come from (a cohort effect) rather than a direct effect of age. For this reason, longitudinal studies in which one group of people is followed as they age offer a superior means of studying the effects of aging. Once again, cross-sectional designs are also commonly used to study sex differences. Since researchers cannot practically or ethically manipulate the sex of their participants they must rely on cross-sectional designs to compare groups of men and women on different outcomes (e.g., verbal ability, substance use, depression). Using these designs researchers have discovered that men are more likely than women to suffer from substance abuse problems while women are more likely than men to suffer from depression. But, using this design it is unclear what is causing these differences. So, using this design it is unclear whether these differences are due to environmental factors like socialization or biological factors like hormones?

When researchers use a participant characteristic to create groups (nationality, cannabis use, age, sex), the independent variable is usually referred to as an experimenter-selected independent variable (as opposed to the experimenter-manipulated independent variables used in experimental research). Figure 6.1 shows data from a hypothetical study on the relationship between whether people make a daily list of things to do (a “to-do list”) and stress. Notice that it is unclear whether this is an experiment or a cross-sectional study because it is unclear whether the independent variable was manipulated by the researcher or simply selected by the researcher. If the researcher randomly assigned some participants to make daily to-do lists and others not to, then the independent variable was experimenter-manipulated and it is a true experiment. If the researcher simply asked participants whether they made daily to-do lists or not, then the independent variable it is experimenter-selected and the study is cross-sectional. The distinction is important because if the study was an experiment, then it could be concluded that making the daily to-do lists reduced participants’ stress. But if it was a cross-sectional study, it could only be concluded that these variables are statistically related. Perhaps being stressed has a negative effect on people’s ability to plan ahead. Or perhaps people who are more conscientious are more likely to make to-do lists and less likely to be stressed. The crucial point is that what defines a study as experimental or cross-sectional l is not the variables being studied, nor whether the variables are quantitative or categorical, nor the type of graph or statistics used to analyze the data. It is how the study is conducted.

Figure 6.1 Results of a Hypothetical Study on Whether People Who Make Daily To-Do Lists Experience Less Stress Than People Who Do Not Make Such Lists

Second, the most common type of non-experimental research conducted in Psychology is correlational research. Correlational research is considered non-experimental because it focuses on the statistical relationship between two variables but does not include the manipulation of an independent variable. More specifically, in correlational research , the researcher measures two continuous variables with little or no attempt to control extraneous variables and then assesses the relationship between them. As an example, a researcher interested in the relationship between self-esteem and school achievement could collect data on students’ self-esteem and their GPAs to see if the two variables are statistically related. Correlational research is very similar to cross-sectional research, and sometimes these terms are used interchangeably. The distinction that will be made in this book is that, rather than comparing two or more pre-existing groups of people as is done with cross-sectional research, correlational research involves correlating two continuous variables (groups are not formed and compared).

Third, observational research is non-experimental because it focuses on making observations of behavior in a natural or laboratory setting without manipulating anything. Milgram’s original obedience study was non-experimental in this way. He was primarily interested in the extent to which participants obeyed the researcher when he told them to shock the confederate and he observed all participants performing the same task under the same conditions. The study by Loftus and Pickrell described at the beginning of this chapter is also a good example of observational research. The variable was whether participants “remembered” having experienced mildly traumatic childhood events (e.g., getting lost in a shopping mall) that they had not actually experienced but that the researchers asked them about repeatedly. In this particular study, nearly a third of the participants “remembered” at least one event. (As with Milgram’s original study, this study inspired several later experiments on the factors that affect false memories.

The types of research we have discussed so far are all quantitative, referring to the fact that the data consist of numbers that are analyzed using statistical techniques. But as you will learn in this chapter, many observational research studies are more qualitative in nature. In qualitative research , the data are usually nonnumerical and therefore cannot be analyzed using statistical techniques. Rosenhan’s observational study of the experience of people in a psychiatric ward was primarily qualitative. The data were the notes taken by the “pseudopatients”—the people pretending to have heard voices—along with their hospital records. Rosenhan’s analysis consists mainly of a written description of the experiences of the pseudopatients, supported by several concrete examples. To illustrate the hospital staff’s tendency to “depersonalize” their patients, he noted, “Upon being admitted, I and other pseudopatients took the initial physical examinations in a semi-public room, where staff members went about their own business as if we were not there” (Rosenhan, 1973, p. 256) [2] . Qualitative data has a separate set of analysis tools depending on the research question. For example, thematic analysis would focus on themes that emerge in the data or conversation analysis would focus on the way the words were said in an interview or focus group.

Internal Validity Revisited

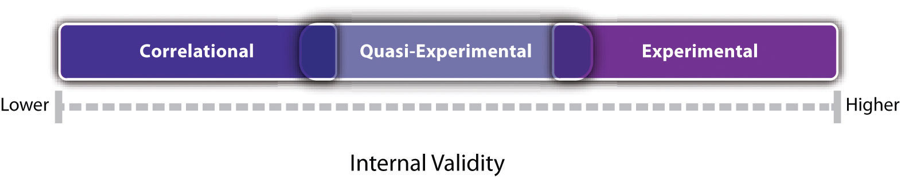

Recall that internal validity is the extent to which the design of a study supports the conclusion that changes in the independent variable caused any observed differences in the dependent variable. Figure 6.2 shows how experimental, quasi-experimental, and non-experimental (correlational) research vary in terms of internal validity. Experimental research tends to be highest in internal validity because the use of manipulation (of the independent variable) and control (of extraneous variables) help to rule out alternative explanations for the observed relationships. If the average score on the dependent variable in an experiment differs across conditions, it is quite likely that the independent variable is responsible for that difference. Non-experimental (correlational) research is lowest in internal validity because these designs fail to use manipulation or control. Quasi-experimental research (which will be described in more detail in a subsequent chapter) is in the middle because it contains some, but not all, of the features of a true experiment. For instance, it may fail to use random assignment to assign participants to groups or fail to use counterbalancing to control for potential order effects. Imagine, for example, that a researcher finds two similar schools, starts an anti-bullying program in one, and then finds fewer bullying incidents in that “treatment school” than in the “control school.” While a comparison is being made with a control condition, the lack of random assignment of children to schools could still mean that students in the treatment school differed from students in the control school in some other way that could explain the difference in bullying (e.g., there may be a selection effect).

Figure 6.2 Internal Validity of Correlation, Quasi-Experimental, and Experimental Studies. Experiments are generally high in internal validity, quasi-experiments lower, and correlation studies lower still.

Notice also in Figure 6.2 that there is some overlap in the internal validity of experiments, quasi-experiments, and correlational studies. For example, a poorly designed experiment that includes many confounding variables can be lower in internal validity than a well-designed quasi-experiment with no obvious confounding variables. Internal validity is also only one of several validities that one might consider, as noted in Chapter 5.

Key Takeaways

- Non-experimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable.

- There are two broad types of non-experimental research. Correlational research that focuses on statistical relationships between variables that are measured but not manipulated, and observational research in which participants are observed and their behavior is recorded without the researcher interfering or manipulating any variables.

- In general, experimental research is high in internal validity, correlational research is low in internal validity, and quasi-experimental research is in between.

- A researcher conducts detailed interviews with unmarried teenage fathers to learn about how they feel and what they think about their role as fathers and summarizes their feelings in a written narrative.

- A researcher measures the impulsivity of a large sample of drivers and looks at the statistical relationship between this variable and the number of traffic tickets the drivers have received.

- A researcher randomly assigns patients with low back pain either to a treatment involving hypnosis or to a treatment involving exercise. She then measures their level of low back pain after 3 months.

- A college instructor gives weekly quizzes to students in one section of his course but no weekly quizzes to students in another section to see whether this has an effect on their test performance.

- Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view . New York, NY: Harper & Row. ↵

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179 , 250–258. ↵

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

Quantitative Research with Nonexperimental Designs

by Janet Salmons, PhD Manager, Sage Research Methods Community

What is the difference between experimental and non-experimental research designs?

There are two types of quantitative research designs: experimental and nonexperimental. This introduction draws from The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation . Leung and Shek (2018) explain:

Experimental research design utilizes the principle of manipulation of the independent variables and examines its cause-and-effect relationship on the dependent variables by controlling the effects of other variables. Usually, the experimenter assigns two or more groups with similar characteristics. Different interventions will be given to the groups. In case there are differences in the outcomes among the groups, the experimenter can conclude that the differences result from the interventions that the experimenter performed. [Learn more about experimental design in an earlier Sage Research Methods Community post, Quantitative Research with Experimental Designs . ] Nonexperimental research designs examine social phenomena without direct manipulation of the conditions that subjects experience. Subjects are not randomly assigned to different groups. As such, evidence that supports the cause-and-effect relationships is largely limited.

There are two main types of nonexperimental research designs: comparative design and correlational design.

In comparative research, the researcher examines the differences between two or more groups on the phenomenon that is being studied. For example, studying gender difference in learning mathematics is a comparative research.

The correlational design is a study of relationships between two or more constructs. A positive correlation means that high values of a variable are associated with high values of another variable. For instance, academic performance of students is positively related to their self-esteem. On the contrary, a negative correlation means that high values of a variable are associated with low values of the other variable. For example, teacher–student conflicts are negatively related to the students’ sense of belonging to the school.

See how researchers use non-experimental research design in this multidisciplinary collection of open-access articles.

Open Access Comparative Studies

Humprecht, E., Hellmueller, L., & Lischka, J. A. (2020). Hostile Emotions in News Comments: A Cross-National Analysis of Facebook Discussions . Social Media + Society . https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120912481

Abstract. Recent work demonstrates that hostile emotions can contribute to a strong polarization of political discussion on social media. However, little is known regarding the extent to which media organizations and media systems trigger hostile emotions. We content-analyzed comments on Facebook pages from six news organizations ( N = 1,800) based in the United States and Germany. Our results indicate that German news organizations’ Facebook comments are more balanced, containing lower levels of hostile emotions. Such emotions are particularly prevalent in the polarized information environment of the United States—in both news posts and comments. Moreover, alternative right-wing media outlets in both countries provoke significantly higher levels of hostile emotions, thus limiting deliberative discussions. Our results demonstrate that the application of technology—such as the use of comment sections—has different implications depending on cultural and social contexts.

Huang, J., Kumar, S., & Hu, C. (2020). Does Culture Matter? A Comparative Study on the Motivations for Online Identity Reconstruction Between China and Malaysia . SAGE Open . https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020929311

Abstract. On social network platforms, people may reconstruct an identity due to various reasons, such as vanity, disinhibition, bridging social capital, and privacy concerns. This study aims to identify cultural differences in the motivations for online identity reconstruction between China and Malaysia. Data were collected from China and Malaysia using an online survey. A total of 815 respondents (418 Chinese and 397 Malaysians) participated in this study. Differences were found not only between Chinese and Malaysian participants but also among participants from different ethnic groups (e.g., the Malaysian-Malays and the Malaysian-Chinese). This study adds knowledge to the research concerning online identity reconstruction by taking into account national culture. It also extends the cross-cultural research concerning social network platforms and sheds light on the specific differences between Chinese and Malaysian participants. The findings of this study can help service providers to deploy specific strategies to better serve social network platform users from different countries.

Kalogeropoulos, A., Negredo, S., Picone, I., & Nielsen, R. K. (2017). Who Shares and Comments on News?: A Cross-National Comparative Analysis of Online and Social Media Participation . Social Media + Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117735754

Abstract. In this article, we present a cross-national comparative analysis of which online news users in practice engage with the participatory potential for sharing and commenting on news afforded by interactive features in news websites and social media technologies across a strategic sample of six different countries. Based on data from the 2016 Reuters Institute Digital News Report, and controlling for a range of factors, we find that (1) people who use social media for news and a high number of different social media platforms are more likely to also engage more actively with news outside social media by commenting on news sites and sharing news via email, (2) political partisans on both sides are more likely to engage in sharing and commenting particularly on news stories in social media, and (3) people with high interest in hard news are more likely to comment on news on both news sites and social media and share stores via social media (and people with high interest in any kind of news [hard or soft] are more likely to share stories via email). Our analysis suggests that the online environment reinforces some long-standing inequalities in participation while countering other long-standing inequalities. The findings indicate a self-reinforcing positive spiral where the already motivated are more likely in practice to engage with the potential for participation offered by digital media, and a negative spiral where those who are less engaged participate less.

Phillips, M., & Smith, D. P. (2018). Comparative approaches to gentrification: Lessons from the rural . Dialogues in Human Geography , 8 (1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820617752009

Abstract. The epistemologies and politics of comparative research are prominently debated within urban studies, with ‘comparative urbanism’ emerging as a contemporary lexicon of urban studies. The study of urban gentrification has, after some delay, come to engage with these debates, which can be seen to pose a major challenge to the very concept of gentrification. To date, similar debates or developments have not unfolded within the study of rural gentrification. This article seeks to address some of the challenges posed to gentrification studies through an examination of strategies of comparison and how they might be employed within a comparative study of rural gentrification. Drawing on Tilly ( Big structures Large Processes Huge Comparisons . New York: Russell Sage), examples of four ‘strategies of comparison’ are identified within studies of urban and rural gentrification, before the paper explores how ‘geographies of the concept’ and ‘geographies of the phenomenon’ of rural gentrification in the United Kingdom, United States and France may be investigated using Latour’s ( Pandora’s Hope . London: Harvard University Press) notion of ‘circulatory sociologies of translation’. The aim of our comparative discussion is to open up dialogues on the challenges of comparative studies that employ conceptions of gentrification and also to promote reflections of the metrocentricity of recent discussions of comparative research.

Yaşar, H., & Sağsan, M. (2020). The Mediating Effect of Organizational Stress on Organizational Culture and Time Management: A Comparative Study With Two Universities. SAGE Open . https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020919507

Abstract. This research was designed to investigate whether organizational stress had an intermediary role in the effect of Hofstede cultural dimensions on time management. Near East University from Cyprus, which represents the individual culture, and Hakkari University from Turkey representing the collectivist culture were selected for the research analyses. In all, 638 administrative and academic members from both universities were interviewed face-to-face on a voluntary basis, and data were collected by the simple random sampling method. The research findings suggest that time should be managed after identifying the type of culture—individualistic or collectivist—to decrease the level of stress experienced by university staff. In other words, Hofstede’s cultural dimension has an impact on time management, and organizational stress has a partial mediation effect on this dimension. Although the variables in the study have been studied in the literature together with many different factors, Hofstede is significant in terms of determining the role of organizational stress in the effect of cultural dimensions on time management. The effectiveness of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions through organizational stress in time management allows business and project plans to be carried out in a way that manages individual, team or departmental performances taking into account the organizational stress elements. It is considered that this study will particularly be effective in medicine, project management, and independent auditing.

Open Access Correlational Studies

Adams, R. V., & Blair, E. (2019). Impact of Time Management Behaviors on Undergraduate Engineering Students’ Performance . SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018824506

Abstract. Effective time management is associated with greater academic performance and lower levels of anxiety in students; however many students find it hard to find a balance between their studies and their day-to-day lives. This article examines the self-reported time management behaviors of undergraduate engineering students using the Time Management Behavior Scale. Correlation analysis, regression analysis, and model reduction are used to attempt to determine which aspects of time management the students practiced, which time management behaviors were more strongly associated with higher grades within the program, and whether or not those students who self-identified with specific time management behaviors achieved better grades in the program. It was found that students’ perceived control of time was the factor that correlated significantly with cumulative grade point average. On average, it was found that time management behaviors were not significantly different across gender, age, entry qualification, and time already spent in the program.

Cooper, B., & Glaesser, J. (2010). Contrasting Variable-Analytic and Case-Based Approaches to the Analysis of Survey Datasets: Exploring How Achievement Varies by Ability across Configurations of Social Class and Sex. Methodological Innovations Online, 5(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.4256/mio.2010.0007

Abstract. The context for this paper is the ongoing debate concerning the relative merits, for the analysis of quantitative data, of, on the one hand, variable-analytic correlational methods, and, on the other, the case-based set theoretic methods developed by Charles Ragin. While correlational approaches, based in linear algebra, typically use regression to establish the net effects of several “independent” variables on an outcome, the set theoretic approach analyses, more holistically, the conjunctions of factors sufficient and/or necessary for an outcome to occur. Here, in order to bring out key differences between the approaches, we focus our attention on the basic building blocks of the two approaches: respectively, the concept of linear correlation and the concept of a sufficient and/or necessary condition. We initially use invented data (for ability, educational achievement, and social class) to simulate what is at stake in this methodological debate and we then employ data taken from the British National Child Development Study to explore the structuring of the relationship between respondents' early measured ability and later educational achievement across various configurations of parental and grandparental class origin and sex. The substantive idea informing the analysis, derived from Boudon's work, is that, for respondents from higher class origins, ability will tend to be sufficient but not necessary for later educational achievement while, for lower class respondents, ability will tend to be necessary but not sufficient. We compare correlational analyses, controlling for class and gender, with fuzzy set analyses to show that set theoretic indices can better capture these varying relationships than correlational measures. In conclusion, we briefly consider how our demonstration of some of the advantages of the set theoretic approach for modelling empirical relationships might be related to the debate concerning the relation between observed regularities and causal mechanisms.

Fang, C., Gai, Q., He, C., & Shi, Q. (2020). The Experience of Poverty Reduction in Rural China. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020982288

Abstract. Since 1978, China has greatly reduced the rural poverty rate. This article provides an overview of the experience of China’s poverty reduction. Using panel data from 1996 to 2013 to calculate farmers’ income dynamics, we found that the pace of poverty reduction was relatively slow from 1996 to 2002 and that the rate of reversion to poverty was high. Since 2003, the pace of poverty reduction has accelerated, whereas the rate of reversion has decreased. Using econometric ordinary least squares and probit models, we explore the factors that drive poverty reduction. We found correlational evidence that the main reasons for poverty reduction in China since 1996 have been the increase in income from household farms and migrant work. In addition, rural public insurance prevented farmers from falling into poverty.

Hayn-Leichsenring, G. U., Lehmann, T., & Redies, C. (2017). Subjective Ratings of Beauty and Aesthetics: Correlations With Statistical Image Properties in Western Oil Paintings . I-Perception. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041669517715474

Abstract. For centuries, oil paintings have been a major segment of the visual arts. The JenAesthetics data set consists of a large number of high-quality images of oil paintings of Western provenance from different art periods. With this database, we studied the relationship between objective image measures and subjective evaluations of the images, especially evaluations on aesthetics (defined as artistic value) and beauty (defined as individual liking). The objective measures represented low-level statistical image properties that have been associated with aesthetic value in previous research. Subjective rating scores on aesthetics and beauty correlated not only with each other but also with different combinations of the objective measures. Furthermore, we found that paintings from different art periods vary with regard to the objective measures, that is, they exhibit specific patterns of statistical image properties. In addition, clusters of participants preferred different combinations of these properties. In conclusion, the results of the present study provide evidence that statistical image properties vary between art periods and subject matters and, in addition, they correlate with the subjective evaluation of paintings by the participants.

Srinivasan P, Rentala S, Kumar P. Impulsivity and Aggression Among Male Delinquent Adolescents Residing in Observation Homes—A Descriptive Correlation Study from East India . Journal of Indian Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health . 2022;18(4):327-336. doi: 10.1177/09731342231171305

Aggression and crime are connected and highly reported among juveniles in recent times as compared to adults, which ends up in delinquency. It is not just aggression that dominates but the associated impulsiveness also plays a vital role. This study was intended to assess impulsivity and aggression, and their relationship among male delinquent adolescents residing in observation homes. A quantitative research approach with the nonexperimental descriptive correlation design was adopted. One hundred and seventy-nine male delinquent adolescents residing in 2 observation homes in the state of Bihar, India, were selected by convenience sampling technique. The standardized Buss & Perry Aggression questionnaire, and Barratt Impulsiveness scale were used for collecting the data regarding impulsivity and aggression among male delinquent adolescents.

Yamak, O. U., & Eyupoglu, S. Z. (2021). Authentic Leadership and Service Innovative Behavior: Mediating Role of Proactive Personality . SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244021989629

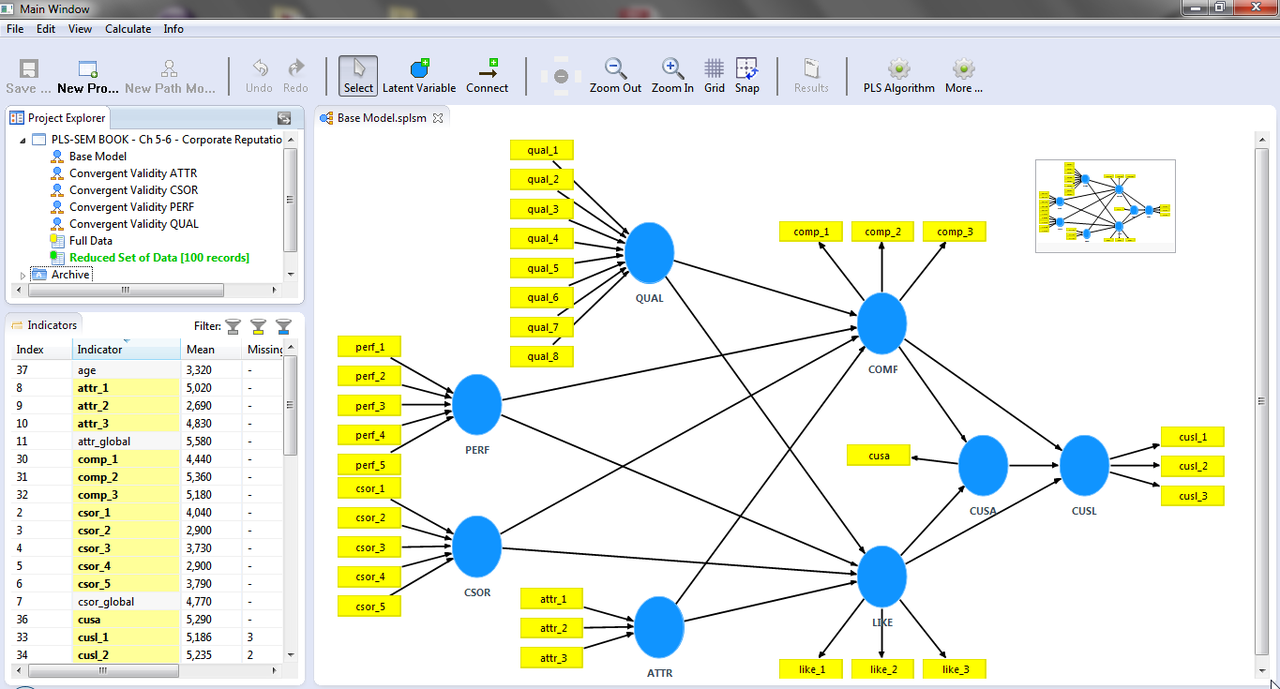

Abstract. The present study aims to examine the effect of authentic leadership (AL) on service innovative behavior (SIB) of employees as well as to identify whether proactive personality (PP) mediates this connection at an individual level. The quantitative cross-sectional study design was utilized to gather information from a study sample which consisted of 428 front-line employees (FLE) working at banks located in North Cyprus. Specifically, the study uses confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), correlation, structural equation modeling (SEM), and bootstrapping techniques to test the hypothesized relationships. The results reveal that both AL and PP have a significant positive effect on SIB; AL has a positive impact on PP of FLE, and PP plays a partial mediating role between AL and SIB of FLE. By relating the study findings, authenticity and proactivity in the banking sector in North Cyprus play a critical role in fostering the innovative behaviors of FLE. The study also discusses the practical and managerial implications, as well as the future scope.

Books about Quantitative Methods from Sage Publishing

Use the code COMMUNITY3 for a 20% discount when you order her book, valid worldwide until March 31, 2024.

The Research Experience: Planning, Conducting, and Reporting Research by Ann Sloan Devlin (2020). (See Sage Research Methods Community posts by Dr. Devlin.)

Understanding Quantitative Data in Educational Research by Nicoleta Gaciu (2021).

Essentials of Social Statistics for a Diverse Society by Anna Leon-Guerrero, Chava Frankfort-Nachmias, and Georgiann Davis.(2020). (See an author interview for more on this book.)

Understanding Correlation Matrices by Alexandria Hadd and Joseph Lee Rodgers (2021)

Know Your Variables: Little Quick Fix and other titles in the LQF series by John MacInnes

Research Methods for the Behavioral Sciences by Gregory J. Privitera (2022)

Reference Frey, B. (2018). The SAGE encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation (Vols. 1-4). Thousand Oaks,, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781506326139

More posts about quantitative research methods

Sample a selection of the most helpful methods videos and guides published in 2024 on the Sage Research Methods online platform with free access.

Listen to this interview, and check out Rhys Jones’ latest book: Statistical Literacy: A Beginner's Guide.

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) enables researchers to model and estimate complex cause-effects relationship models

Find tips to help you share your research and numerical findings.

Dr. Stephen Gorard defines and explains randomness in a research context.

Mentor in Residence Stephen Gorard explains how researchers can think about predicting results.

Instructional tips for teaching quantitative data analysis.

Images contain information absent in text, and this extra information presents opportunities and challenges. It is an opportunity because one image can document variables with which text sources (newspaper articles, speeches or legislative documents) struggle or on datasets too large to feasibly code manually. Learn how to overcome the challenges.

Tips for dealing with missing data from Dr. Stephen Gorard, author of How to Make Sense of Statistics.

Learn more about standard deviation from a paper and presentation from Dr. Stephen Gorard.

How can you use Excel in your data analysis? Charlotte Brookfield explains!

Have you seen Dr. Gorard use card tricks to teach research methods? Watch this video!

Don’t have funds for data analysis software? Use Excel! Learn how in this interview with Charlotte Brookfield.

Listen to Dr. Stephen Gorard discuss his no-nonsense approach to statistics.

Professor Julie Scott Jones discusses lessons learned from teaching quantitative research methods online.

After 20 years of teaching research and quantitative methods to students in Political Science in the US, UK, and the EU, Dr. Loveless has developed a teaching method that has resulted in greater student success in statistics in each passing year

Mentor in Residence Stephen Gorard explains how to use population data.

Dr. Ann Sloan Devlin, author of The Research Experience, discusses first steps in data analysis for quantitative studies.

Want to use R for statistical analysis? These open-access resources might help!

Learn about R and find books about using this language and environment for statistical computing and graphics.

Learn about research with online Experiments from Dr. Giuseppe Veltri.

What is the difference between experimental and non-experimental research design? We look at how non-experimental design distinguishes itself from experimental design and how it can be applied in the research process with open-access examples.

Download the free report from the project, “Fostering Data Literacy: Teaching with Quantitative Data in the Social Sciences.” This report explores two key challenges to teaching with data: helping students overcome anxieties about math and synchronizing the interconnected methodological, software, and analytic competencies.

In the day-to-day of political communication, politicians constantly decide how to amplify or constrain emotional expression, in service of signalling policy priorities or persuading colleagues and voters. We propose a new method for quantifying emotionality in politics using the transcribed text of politicians’ speeches. This new approach, described in more detail below, uses computational linguistics tools and can be validated against human judgments of emotionality.

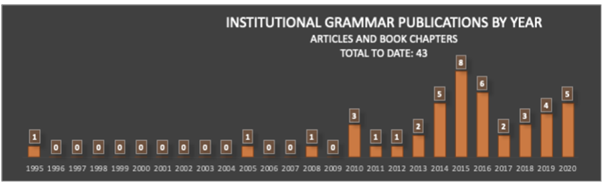

Institutions — rules that govern behavior — are among the most important social artifacts of society. So it should come as a great shock that we still understand them so poorly. How are institutions designed? What makes institutions work? Is there a way to systematically compare the language of different institutions? One recent advance is bringing us closer to making these questions quantitatively approachable. The Institutional Grammar (IG) 2.0 is an analytical approach, drawn directly from classic work by Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom, that is providing the foundation for computational representations of institutions. IG 2.0 is a formalism for translating between human-language outputs — policies, rules, laws, decisions, and the like. It defines abstract structures precisely enough to be manipulable by computer. Recent work, supported by the National Science Foundation ( RCN: Coordinating and Advancing Analytical Approaches for Policy Design & GCR: Collaborative Research: Jumpstarting Successful Open-Source Software Projects With Evidence-Based Rules and Structures ), leveraging recent advances in natural language processing highlighted on this blog , is vastly accelerating the rate and quality of computational translations of written rules.

What is case study methodology? It is unique given one characteristic: case studies draw from more than one data source. In this post find definitions and a collection of multidisciplinary examples.

Learn about experimental research designs and read open-access studies.

In the field of artificial intelligence (AI), Transformers have revolutionized language analysis. Never before has a new technology universally improved the benchmarks of nearly all language processing tasks: e.g., general language understanding, question - answering , and Web search . The transformer method itself, which probabilistically models words in their context (i.e. “language modeling”), was introduced in 2017 and the first large-scale pre-trained general purpose transformer, BERT, was released open source from Google in 2018. Since then, BERT has been followed by a wave of new transformer models including GPT, RoBERTa, DistilBERT, XLNet, Transformer-XL, CamemBERT, XLM-RoBERTa, etc. The text package makes all of these language models and many more easily accessible to use for R-users; and includes functions optimized for human-level analyses tailored to social scientists.

This year’s lockdown challenged the absolute core of higher education and accelerated or rather imposed the adoption of digital tooling to fully replace the interactivity of the physical classroom. And while other industries might have suffered losses, the edtech space flourished, with funding for edtech almost doubling in the first half of 2020 vs 2019 . Even before the pandemic, lecturers were starting to feel overwhelmed by the amount of choice to support their teaching. More funding just meant more hype, more tools, and more tools working on similar or slightly improved solutions, making it even harder and more time-consuming to find and adapt them in a rush.

Below, we take a look at several tools and startups that are already supporting many of you in teaching quantitative research methods; and some cool new tools you could use to enhance your classroom.

Pros and Cons of Online Survey Research

Research with black participants: scholars rethink methods and methodology.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Non-experimental research: What it is, overview & advantages

Non-experimental research is the type of research that lacks an independent variable. Instead, the researcher observes the context in which the phenomenon occurs and analyzes it to obtain information.

Unlike experimental research , where the variables are held constant, non-experimental research happens during the study when the researcher cannot control, manipulate or alter the subjects but relies on interpretation or observations to conclude.

This means that the method must not rely on correlations, surveys , or case studies and cannot demonstrate an actual cause and effect relationship.

Characteristics of non-experimental research

Some of the essential characteristics of non-experimental research are necessary for the final results. Let’s talk about them to identify the most critical parts of them.

- Most studies are based on events that occurred previously and are analyzed later.

- In this method, controlled experiments are not performed for reasons such as ethics or morality.

- No study samples are created; on the contrary, the samples or participants already exist and develop in their environment.

- The researcher does not intervene directly in the environment of the sample.

- This method studies the phenomena exactly as they occurred.

Types of non-experimental research

Non-experimental research can take the following forms:

Cross-sectional research : Cross-sectional research is used to observe and analyze the exact time of the research to cover various study groups or samples. This type of research is divided into:

- Descriptive: When values are observed where one or more variables are presented.

- Causal: It is responsible for explaining the reasons and relationship that exists between variables in a given time.

Longitudinal research: In a longitudinal study , researchers aim to analyze the changes and development of the relationships between variables over time. Longitudinal research can be divided into:

- Trend: When they study the changes faced by the study group in general.

- Group evolution: When the study group is a smaller sample.

- Panel: It is in charge of analyzing individual and group changes to discover the factor that produces them.

LEARN ABOUT: Quasi-experimental Research

When to use non-experimental research

Non-experimental research can be applied in the following ways:

- When the research question may be about one variable rather than a statistical relationship about two variables.

- There is a non-causal statistical relationship between variables in the research question.

- The research question has a causal research relationship, but the independent variable cannot be manipulated.

- In exploratory or broad research where a particular experience is confronted.

Advantages and disadvantages

Some advantages of non-experimental research are:

- It is very flexible during the research process

- The cause of the phenomenon is known, and the effect it has is investigated.

- The researcher can define the characteristics of the study group.

Among the disadvantages of non-experimental research are:

- The groups are not representative of the entire population.

- Errors in the methodology may occur, leading to research biases .

Non-experimental research is based on the observation of phenomena in their natural environment. In this way, they can be studied later to reach a conclusion.

Difference between experimental and non-experimental research

Experimental research involves changing variables and randomly assigning conditions to participants. As it can determine the cause, experimental research designs are used for research in medicine, biology, and social science.

Experimental research designs have strict standards for control and establishing validity. Although they may need many resources, they can lead to very interesting results.

Non-experimental research, on the other hand, is usually descriptive or correlational without any explicit changes done by the researcher. You simply describe the situation as it is, or describe a relationship between variables. Without any control, it is difficult to determine causal effects. The validity remains a concern in this type of research. However, it’s’ more regarding the measurements instead of the effects.

LEARN MORE: Descriptive Research vs Correlational Research

Whether you should choose experimental research or non-experimental research design depends on your goals and resources. If you need any help with how to conduct research and collect relevant data, or have queries regarding the best approach for your research goals, contact us today! You can create an account with our survey software and avail of 88+ features including dashboard and reporting for free.

Create a free account

MORE LIKE THIS

2024 QuestionPro Workforce Year in Review

Dec 23, 2024

QuestionPro Workforce Has All The Feels – Release of the New Sentiment Analysis

Dec 19, 2024

The Impact Of Synthetic Data On Modern Research

Companies are losing $ billions with gaps in market research – are you?

Dec 18, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 7: Nonexperimental Research

Overview of Nonexperimental Research

Learning Objectives

- Define nonexperimental research, distinguish it clearly from experimental research, and give several examples.

- Explain when a researcher might choose to conduct nonexperimental research as opposed to experimental research.

What Is Nonexperimental Research?

Nonexperimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable, random assignment of participants to conditions or orders of conditions, or both.

In a sense, it is unfair to define this large and diverse set of approaches collectively by what they are not . But doing so reflects the fact that most researchers in psychology consider the distinction between experimental and nonexperimental research to be an extremely important one. This distinction is because although experimental research can provide strong evidence that changes in an independent variable cause differences in a dependent variable, nonexperimental research generally cannot. As we will see, however, this inability does not mean that nonexperimental research is less important than experimental research or inferior to it in any general sense.

When to Use Nonexperimental Research

As we saw in Chapter 6 , experimental research is appropriate when the researcher has a specific research question or hypothesis about a causal relationship between two variables—and it is possible, feasible, and ethical to manipulate the independent variable and randomly assign participants to conditions or to orders of conditions. It stands to reason, therefore, that nonexperimental research is appropriate—even necessary—when these conditions are not met. There are many ways in which preferring nonexperimental research can be the case.

- The research question or hypothesis can be about a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables (e.g., How accurate are people’s first impressions?).

- The research question can be about a noncausal statistical relationship between variables (e.g., Is there a correlation between verbal intelligence and mathematical intelligence?).

- The research question can be about a causal relationship, but the independent variable cannot be manipulated or participants cannot be randomly assigned to conditions or orders of conditions (e.g., Does damage to a person’s hippocampus impair the formation of long-term memory traces?).

- The research question can be broad and exploratory, or it can be about what it is like to have a particular experience (e.g., What is it like to be a working mother diagnosed with depression?).

Again, the choice between the experimental and nonexperimental approaches is generally dictated by the nature of the research question. If it is about a causal relationship and involves an independent variable that can be manipulated, the experimental approach is typically preferred. Otherwise, the nonexperimental approach is preferred. But the two approaches can also be used to address the same research question in complementary ways. For example, nonexperimental studies establishing that there is a relationship between watching violent television and aggressive behaviour have been complemented by experimental studies confirming that the relationship is a causal one (Bushman & Huesmann, 2001) [1] . Similarly, after his original study, Milgram conducted experiments to explore the factors that affect obedience. He manipulated several independent variables, such as the distance between the experimenter and the participant, the participant and the confederate, and the location of the study (Milgram, 1974) [2] .

Types of Nonexperimental Research

Nonexperimental research falls into three broad categories: single-variable research, correlational and quasi-experimental research, and qualitative research. First, research can be nonexperimental because it focuses on a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables. Although there is no widely shared term for this kind of research, we will call it single-variable research . Milgram’s original obedience study was nonexperimental in this way. He was primarily interested in one variable—the extent to which participants obeyed the researcher when he told them to shock the confederate—and he observed all participants performing the same task under the same conditions. The study by Loftus and Pickrell described at the beginning of this chapter is also a good example of single-variable research. The variable was whether participants “remembered” having experienced mildly traumatic childhood events (e.g., getting lost in a shopping mall) that they had not actually experienced but that the research asked them about repeatedly. In this particular study, nearly a third of the participants “remembered” at least one event. (As with Milgram’s original study, this study inspired several later experiments on the factors that affect false memories.)

As these examples make clear, single-variable research can answer interesting and important questions. What it cannot do, however, is answer questions about statistical relationships between variables. This detail is a point that beginning researchers sometimes miss. Imagine, for example, a group of research methods students interested in the relationship between children’s being the victim of bullying and the children’s self-esteem. The first thing that is likely to occur to these researchers is to obtain a sample of middle-school students who have been bullied and then to measure their self-esteem. But this design would be a single-variable study with self-esteem as the only variable. Although it would tell the researchers something about the self-esteem of children who have been bullied, it would not tell them what they really want to know, which is how the self-esteem of children who have been bullied compares with the self-esteem of children who have not. Is it lower? Is it the same? Could it even be higher? To answer this question, their sample would also have to include middle-school students who have not been bullied thereby introducing another variable.

Research can also be nonexperimental because it focuses on a statistical relationship between two variables but does not include the manipulation of an independent variable, random assignment of participants to conditions or orders of conditions, or both. This kind of research takes two basic forms: correlational research and quasi-experimental research. In correlational research , the researcher measures the two variables of interest with little or no attempt to control extraneous variables and then assesses the relationship between them. A research methods student who finds out whether each of several middle-school students has been bullied and then measures each student’s self-esteem is conducting correlational research. In quasi-experimental research , the researcher manipulates an independent variable but does not randomly assign participants to conditions or orders of conditions. For example, a researcher might start an antibullying program (a kind of treatment) at one school and compare the incidence of bullying at that school with the incidence at a similar school that has no antibullying program.

The final way in which research can be nonexperimental is that it can be qualitative. The types of research we have discussed so far are all quantitative, referring to the fact that the data consist of numbers that are analyzed using statistical techniques. In qualitative research , the data are usually nonnumerical and therefore cannot be analyzed using statistical techniques. Rosenhan’s study of the experience of people in a psychiatric ward was primarily qualitative. The data were the notes taken by the “pseudopatients”—the people pretending to have heard voices—along with their hospital records. Rosenhan’s analysis consists mainly of a written description of the experiences of the pseudopatients, supported by several concrete examples. To illustrate the hospital staff’s tendency to “depersonalize” their patients, he noted, “Upon being admitted, I and other pseudopatients took the initial physical examinations in a semipublic room, where staff members went about their own business as if we were not there” (Rosenhan, 1973, p. 256). [3] Qualitative data has a separate set of analysis tools depending on the research question. For example, thematic analysis would focus on themes that emerge in the data or conversation analysis would focus on the way the words were said in an interview or focus group.

Internal Validity Revisited

Recall that internal validity is the extent to which the design of a study supports the conclusion that changes in the independent variable caused any observed differences in the dependent variable. Figure 7.1 shows how experimental, quasi-experimental, and correlational research vary in terms of internal validity. Experimental research tends to be highest because it addresses the directionality and third-variable problems through manipulation and the control of extraneous variables through random assignment. If the average score on the dependent variable in an experiment differs across conditions, it is quite likely that the independent variable is responsible for that difference. Correlational research is lowest because it fails to address either problem. If the average score on the dependent variable differs across levels of the independent variable, it could be that the independent variable is responsible, but there are other interpretations. In some situations, the direction of causality could be reversed. In others, there could be a third variable that is causing differences in both the independent and dependent variables. Quasi-experimental research is in the middle because the manipulation of the independent variable addresses some problems, but the lack of random assignment and experimental control fails to address others. Imagine, for example, that a researcher finds two similar schools, starts an antibullying program in one, and then finds fewer bullying incidents in that “treatment school” than in the “control school.” There is no directionality problem because clearly the number of bullying incidents did not determine which school got the program. However, the lack of random assignment of children to schools could still mean that students in the treatment school differed from students in the control school in some other way that could explain the difference in bullying.

Notice also in Figure 7.1 that there is some overlap in the internal validity of experiments, quasi-experiments, and correlational studies. For example, a poorly designed experiment that includes many confounding variables can be lower in internal validity than a well designed quasi-experiment with no obvious confounding variables. Internal validity is also only one of several validities that one might consider, as noted in Chapter 5.

Key Takeaways

- Nonexperimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable, control of extraneous variables through random assignment, or both.

- There are three broad types of nonexperimental research. Single-variable research focuses on a single variable rather than a relationship between variables. Correlational and quasi-experimental research focus on a statistical relationship but lack manipulation or random assignment. Qualitative research focuses on broader research questions, typically involves collecting large amounts of data from a small number of participants, and analyses the data nonstatistically.

- In general, experimental research is high in internal validity, correlational research is low in internal validity, and quasi-experimental research is in between.

Discussion: For each of the following studies, decide which type of research design it is and explain why.

- A researcher conducts detailed interviews with unmarried teenage fathers to learn about how they feel and what they think about their role as fathers and summarizes their feelings in a written narrative.

- A researcher measures the impulsivity of a large sample of drivers and looks at the statistical relationship between this variable and the number of traffic tickets the drivers have received.

- A researcher randomly assigns patients with low back pain either to a treatment involving hypnosis or to a treatment involving exercise. She then measures their level of low back pain after 3 months.

- A college instructor gives weekly quizzes to students in one section of his course but no weekly quizzes to students in another section to see whether this has an effect on their test performance.

- Bushman, B. J., & Huesmann, L. R. (2001). Effects of televised violence on aggression. In D. Singer & J. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media (pp. 223–254). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ↵

- Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view . New York, NY: Harper & Row. ↵

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179 , 250–258. ↵

Research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable, random assignment of participants to conditions or orders of conditions, or both.

Research that focuses on a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables.

The researcher measures the two variables of interest with little or no attempt to control extraneous variables and then assesses the relationship between them.

The researcher manipulates an independent variable but does not randomly assign participants to conditions or orders of conditions.

Research Methods in Psychology - 2nd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2015 by Paul C. Price, Rajiv Jhangiani, & I-Chant A. Chiang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Privacy Policy

Home » Descriptive Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Descriptive Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Table of Contents

Descriptive research design is a crucial methodology in social sciences, education, healthcare, and business research. It focuses on describing characteristics, behaviors, or phenomena as they exist without influencing or manipulating the study environment. This type of research provides a snapshot of specific conditions or attributes, making it an essential approach for understanding trends, patterns, and relationships.

This article explores the concept of descriptive research design, its types, methods, and practical examples, providing a comprehensive understanding of its significance and applications.

Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design is a systematic methodology used to describe the characteristics of a population, event, or phenomenon. Unlike experimental research, which tests hypotheses, descriptive research answers “what,” “where,” “when,” and “how” questions. It does not examine causation but rather provides detailed information about existing conditions.

For example, a study describing the demographics of university students enrolled in online courses would employ a descriptive research design.

Importance of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design is vital for:

- Establishing Baseline Data: It provides foundational knowledge to guide further research.

- Identifying Trends: It captures trends and patterns in behavior or phenomena.

- Informing Decision-Making: Organizations and policymakers rely on descriptive research for data-driven decisions.

- Understanding Complex Phenomena: It helps summarize and explain intricate systems or populations.

This design is widely used in fields such as sociology, psychology, marketing, and healthcare to generate valuable insights.

Types of Descriptive Research Design

1. cross-sectional research.

This type involves collecting data from a population or sample at a single point in time.

- Purpose: To describe the current status or characteristics of a population.

- Example: A survey measuring customer satisfaction with a product conducted in January.

2. Longitudinal Research

Longitudinal research collects data from the same subjects over an extended period, allowing researchers to observe changes and trends.

- Purpose: To identify patterns or changes over time.

- Example: Tracking changes in dietary habits among adolescents over five years.

3. Comparative Research

This design compares two or more groups or phenomena to highlight differences and similarities.

- Purpose: To explore variations and relationships between subjects.

- Example: Comparing stress levels between urban and rural employees.

4. Case Study Research

Case studies provide an in-depth examination of a single subject, group, or event.

- Purpose: To gain detailed insights into complex issues.

- Example: Analyzing the strategies of a successful startup to identify factors contributing to its growth.

Methods of Descriptive Research Design

1. surveys and questionnaires.

Surveys are the most common method in descriptive research, using structured or semi-structured questions to gather data.

- Easy to administer to large populations.

- Cost-effective.

- Example: Conducting a survey to determine customer preferences for smartphone features.

2. Observations

This method involves observing and recording behaviors, events, or conditions without interference.

- Provides real-time, naturalistic data.

- Useful for studying non-verbal behaviors.

- Example: Observing classroom interactions to analyze teacher-student dynamics.

Types of Observations

- Example: Observing a team meeting as a team member.

- Example: Watching interactions from a one-way mirror.

3. Secondary Data Analysis

Analyzing pre-existing data, such as government reports, academic articles, or historical records.

- Saves time and resources.

- Provides access to large datasets.

- Example: Using census data to describe population growth trends.

4. Interviews

Interviews involve asking open-ended or structured questions to gather in-depth information.

- Offers detailed insights and clarifications.

- Facilitates exploration of subjective experiences.

- Example: Conducting interviews with employees to understand workplace satisfaction.

5. Case Studies

Involves a deep dive into a specific instance to understand complex phenomena.

- Provides rich, contextualized data.

- Suitable for unique or rare cases.

- Example: Studying the response of a hospital to a public health emergency.

Steps in Conducting Descriptive Research

Step 1: define the research problem.

Clearly outline what you aim to describe and why it is significant.

- Example: “What are the shopping preferences of millennials in urban areas?”

Step 2: Select the Population or Sample

Identify the group you will study and ensure it represents the target population.

- Example: Randomly selecting 500 participants from an urban demographic.

Step 3: Choose the Data Collection Method

Select the most appropriate method based on the research problem and objectives.

- Example: Using a survey to collect data on customer satisfaction.

Step 4: Gather Data

Administer the survey, conduct interviews, or collect observations systematically.

Step 5: Analyze Data

Summarize findings using statistical or thematic analysis, depending on the nature of the data.

- Quantitative Data: Use statistical tools to identify trends.

- Qualitative Data: Use coding techniques to identify themes.

Step 6: Report Results

Present findings clearly and concisely, often with visuals like graphs, charts, and tables.

Examples of Descriptive Research Design

1. healthcare research.

Study: Assessing patient satisfaction in a hospital.

- Method: Distributing surveys to patients.

- Outcome: Identified areas of improvement in hospital services, such as wait times and staff communication.

2. Marketing Research

Study: Exploring customer preferences for eco-friendly packaging.

- Method: Conducting interviews and focus groups.

- Outcome: Revealed that consumers prefer biodegradable packaging and are willing to pay a premium for it.

3. Education Research

Study: Analyzing attendance patterns among college students.

- Method: Collecting secondary data from attendance records.

- Outcome: Found that attendance declines during midterm weeks, suggesting a need for academic support.

4. Social Research

Study: Examining the impact of social media usage on youth communication skills.

- Method: Observing and surveying participants.

- Outcome: Highlighted that frequent social media use correlates with reduced face-to-face communication skills.

Advantages of Descriptive Research Design

- Easy Implementation: Methods like surveys and observations are straightforward and cost-effective.

- Broad Applications: Can be used across disciplines to gather diverse data.

- Non-Intrusive: Describes phenomena without altering them, preserving natural behavior.

- Rich Data: Provides detailed insights into current states or conditions.

Limitations of Descriptive Research Design

- No Causal Relationships: It does not establish cause-and-effect relationships.

- Bias Potential: Surveys and observations may be subject to bias.

- Limited Scope: Restricted to describing existing conditions, limiting predictive capabilities.

Descriptive research design is an invaluable tool for understanding the characteristics and trends of a population or phenomenon. By employing methods such as surveys, observations, and secondary data analysis, researchers can gather rich, detailed insights that inform decision-making and guide further studies. While it does not explore causation, descriptive research provides a foundation for hypotheses and experimental research, making it a cornerstone of empirical inquiry.

- Creswell, J. W. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . Sage Publications.

- Babbie, E. (2020). The Practice of Social Research . Cengage Learning.

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social Research Methods . Oxford University Press.

- Silverman, D. (2020). Interpreting Qualitative Data . Sage Publications.

- Flick, U. (2018). An Introduction to Qualitative Research . Sage Publications.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Textual Analysis – Types, Examples and Guide

Transformative Design – Methods, Types, Guide

Qualitative Research Methods

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3.7 Research Design II: Non-Experimental Designs

Researchers who are simply interested in describing characteristics of people, describing relationships between variables, and using those relationships to make predictions can use a non-experimental research design. Using the non-experimental approach, the researcher simply measures variables as they naturally occur, but they do not manipulate them.

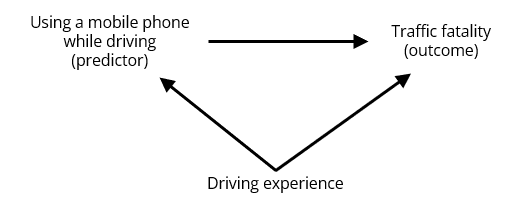

For instance, if a researcher is interested in measuring the number of traffic fatalities in Queensland last year that involved mobile phones, a researcher may not be able to manipulate ‘mobile phone use while driving’, but can simply collect data about a phenomenon that has already occurred. Another example would be standing at a busy intersection and recording the driver’s gender and whether or not they were using a mobile phone while they pass through the intersection, and then analysing the data to see whether men or women are more likely to use a mobile phone when driving. Again, this time, the researcher is just observing the variables (use of mobile phone and gender) and is not manipulating anything.

It is important to point out that ‘non-experimental’ does not mean nonscientific. Non-experimental research is still scientific in nature. It can be used to fulfil two of the three goals of science (to describe and to predict). However, unlike experimental research, we cannot make causal conclusions using this method as the researcher does not have full control of all aspects of the design. With the example we used above, it is possible that there is another variable that is not part of the research hypothesis but that causes both the predictor and the outcome variable and thus produces the observed correlation between them.

There are different examples of non-experimental designs and we will cover some of these types below.

Case Studies

Case studies involve the idiographic, observational (and/or interview) study of an individual or individuals by the researcher, such as within a clinical context where the focus might be on the participant’s lived experience. A famous example of a case study in psychology is the case of Phineas Gage. In 1848, Gage, a railroad worker, survived a severe brain injury when a metal rod was accidentally driven through his skull, damaging his frontal lobes. Remarkably, Gage survived the injury and was able to walk and talk normally, but his personality and behaviour underwent dramatic changes.

Case studies allow for a detailed and in-depth examination of the individual, group, or situation under investigation. Researchers can gather a wealth of information about the person or phenomenon being studied. Unique or rare cases (like Phineas Gage) are particularly useful for studying unique or rare cases that may not be easily observed or studied in other ways. Case studies can be used to generate hypotheses or ideas about potential cause-and-effect relationships that can be tested in future research.

However, as with any research designs, case studies are limited due to the following reasons:

- Limited generalisability: Due to the focus on a single individual, group, or situation, case studies have limited generalisability to larger populations. It may be difficult to generalise findings from a case study to the wider population.

- Subjectivity: Case studies are often subjective, as researchers may have personal biases or interpretations that influence their analysis and conclusions.

- Lack of control: Case studies lack experimental control, which makes it difficult to establish cause-and-effect relationships. It is also difficult to replicate the same conditions across different cases, making it difficult to determine if the findings are consistent.

Quasi-Experimental Designs

A quasi-experimental design is essentially a hybrid of experimental and non-experimental designs. It aims to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between an independent and dependent variable. However, unlike a true experimental design, a quasi-experiment does not rely on random assignment. Instead, subjects are assigned to groups based on non-random criteria.

Quasi-experimental designs are common in psychology research and feature non-random assignment to condition and/or non-manipulation of independent variables, often through necessity. As an example, imagine that some school authorities in Queensland want to implement a new math curriculum and they are interested in determining whether the curriculum is effective in improving student performance. The school authorities decide to implement the new curriculum in one school but not in another. They then compare the test scores of the students in both schools before and after the implementation of the new curriculum.

Since the assignment of the schools to the different conditions (new versus old curriculum) was not random, this is a quasi-experimental design. The study attempts to establish a causal relationship between the new curriculum and student performance by comparing the pre-post scores of the two groups. However, there may be other factors that could account for the differences observed between the two groups, such as differences in student populations or teacher quality. Therefore, the study has limited internal validity.

A Contemporary Approach to Research and Statistics in Psychology Copyright © 2023 by Klaire Somoray is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Non-experimental (correlational) research is lowest in internal validity because these designs fail to use manipulation or control. Quasi-experimental research (which will be described in more detail in a subsequent chapter) is in the middle because it contains some, but not all, of the features of a true experiment.

Feb 3, 2023 · What is the difference between experimental and non-experimental research designs? There are two types of quantitative research designs: experimental and nonexperimental. This introduction draws from The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation. Leung and Shek (2018) explain: